John Ridlon

The Art of John Ridlon: A Journey Through Abstract Expressionism

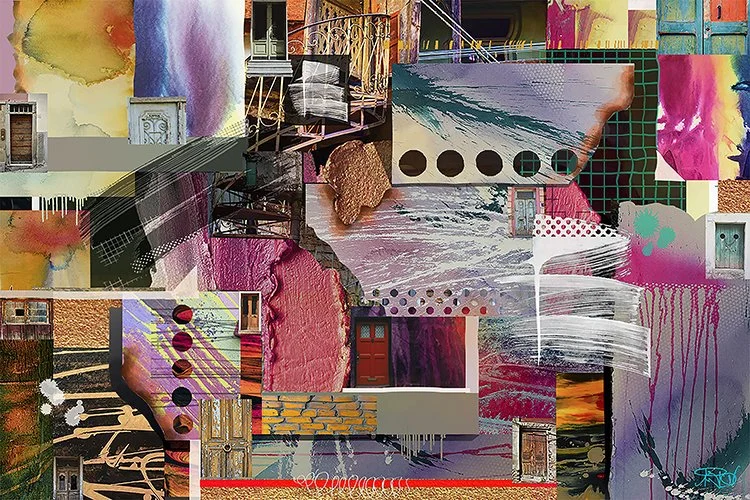

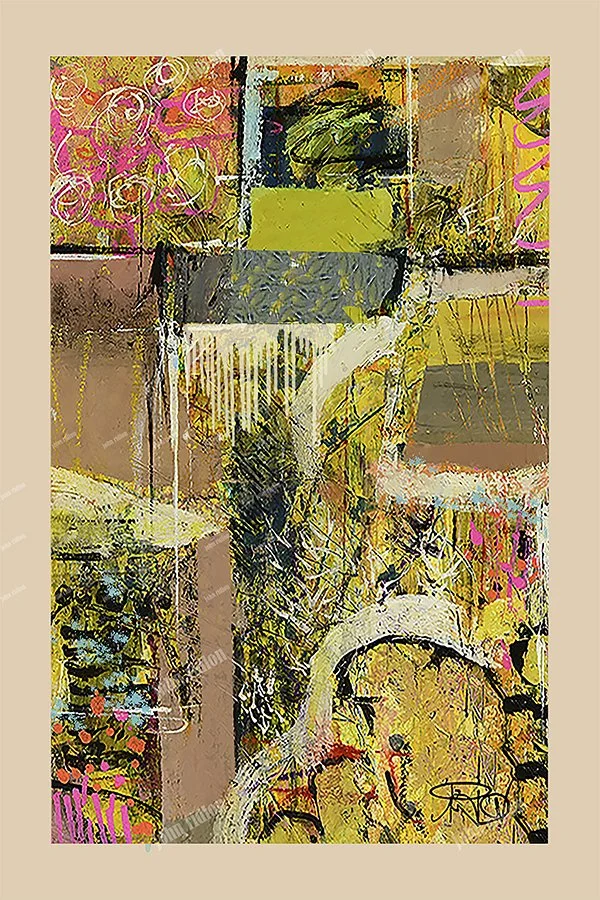

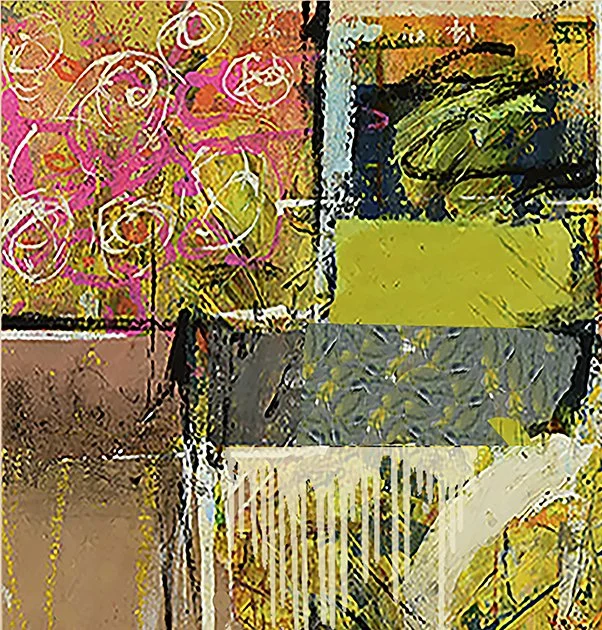

The Golden Staircase

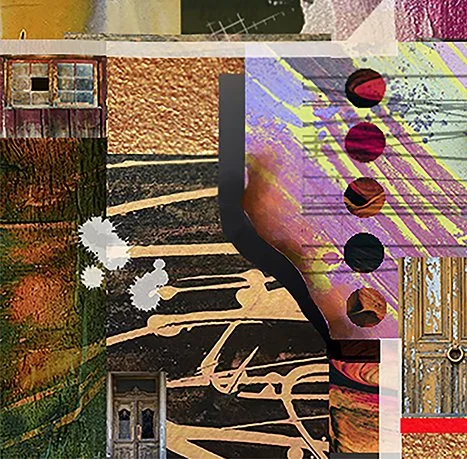

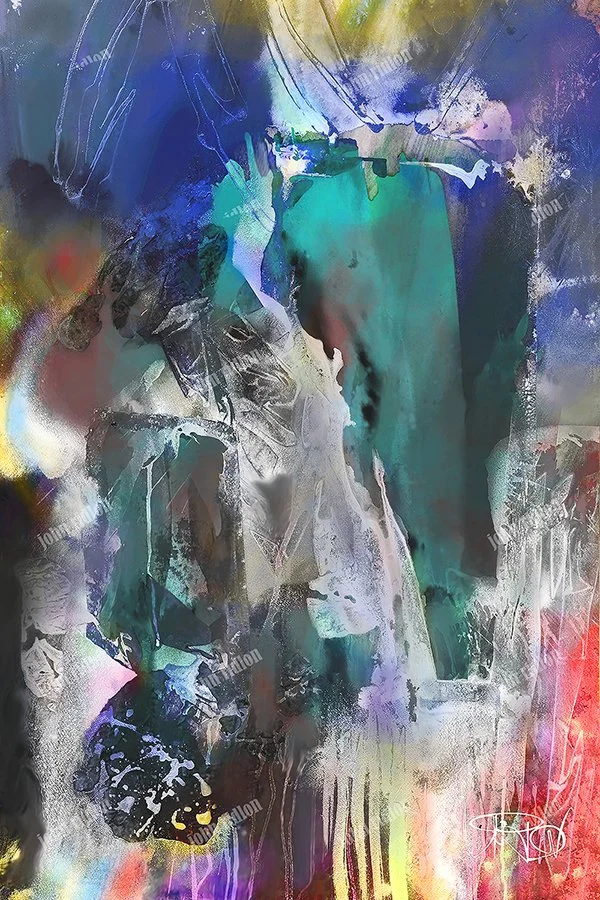

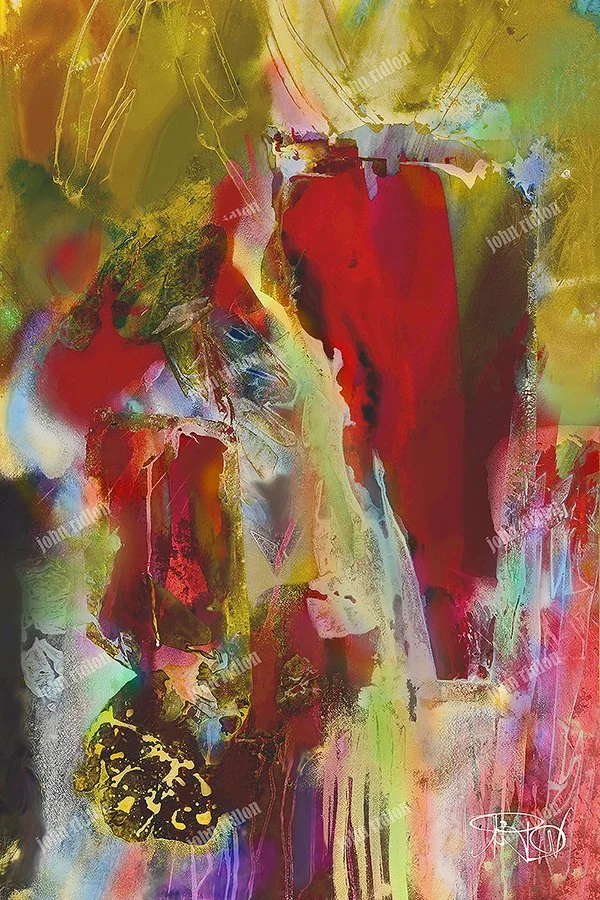

Underneath the Mask

I Am The Mask

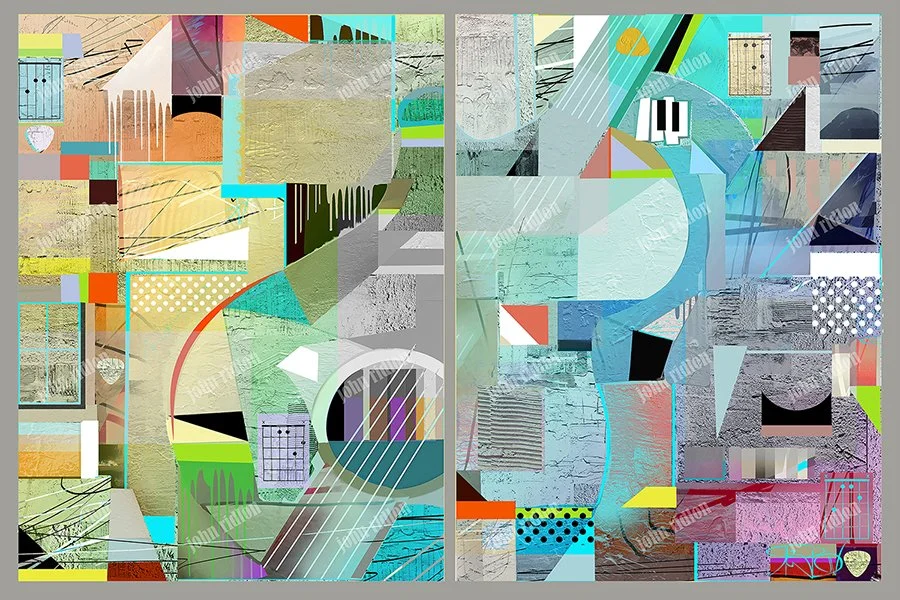

La Guitara Grande

La Guitara

La Guitara Version 2

La Guitara Version 3

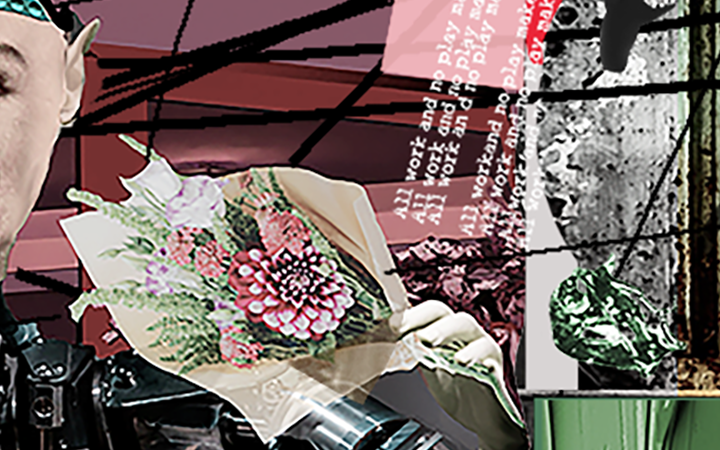

Hello! Welcome! Forward into the Past

Carnival

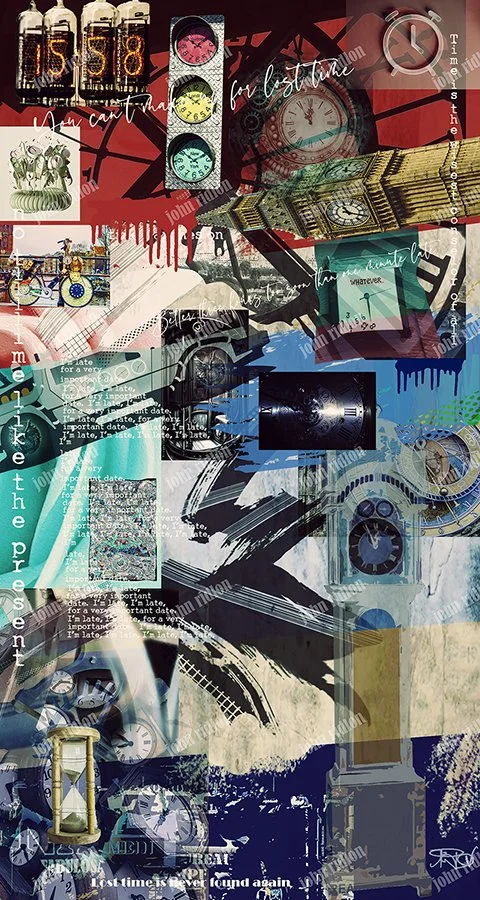

March of Time

Knock on Wood

Clangorama

Pellucidia1

Arrival

Seraphic Matrix 3

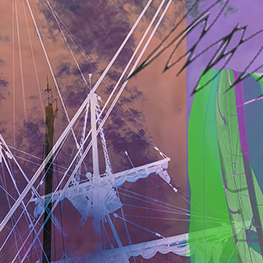

Aviation

Pellucidia 2

Clangorama 2

Trains

Seraphic Matrix 2

Let’s Sail

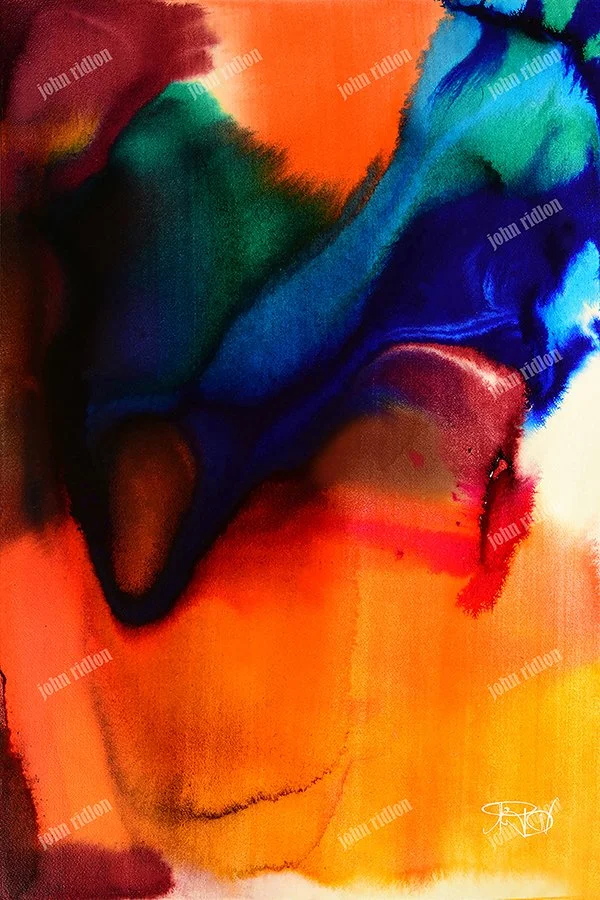

Flash Dance

Seascape

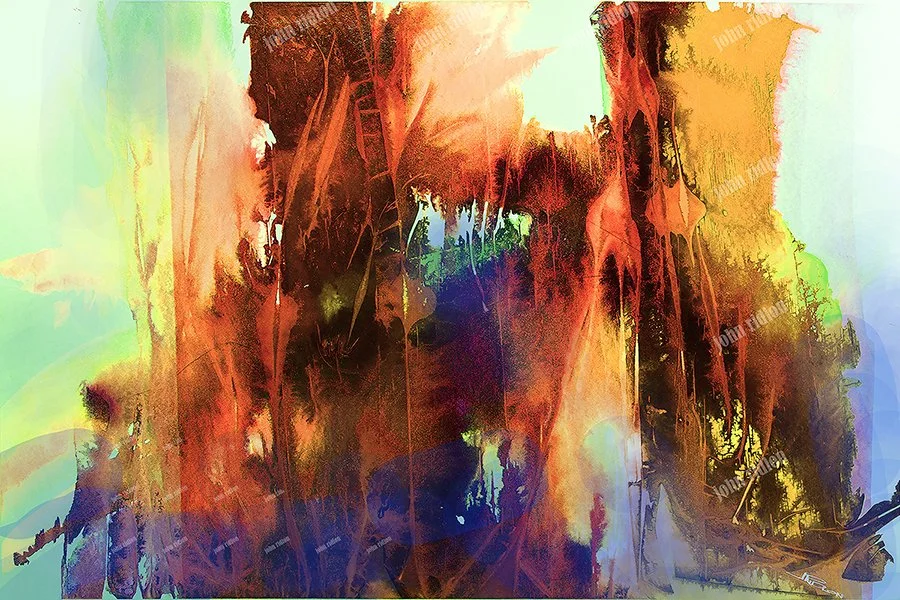

Wild Fire

White Water

Seraphic Matrix

Chimeria.

Flash Dance 3

Paradigm iV

Falling Water

Falling Water 2

Paradigm X

Candalor

Pellucidia 3

The Rise of Abstract Art: From Romanticism to Neo-Plasticism

19th Century Europe: The Seeds of Abstraction

As the 19th century unfolded, the influence of the church as a patron of the arts waned, giving way to private support from an increasingly engaged public. This shift allowed artists greater independence and creative freedom, setting the stage for radical transformations in artistic expression.

Three major movements—Romanticism, Impressionism, and Expressionism—played pivotal roles in loosening the grip of realism and paving the way for abstraction. Romanticism emphasized emotion and individualism, Impressionism captured fleeting light and atmosphere, and Expressionism delved into psychological depth and raw feeling.

Artists like John Constable, J.M.W. Turner, and Camille Corot began exploring the natural world with a more subjective lens, leading to the plein air techniques of the Barbizon school and later the Impressionists. Their work shifted focus from precise depiction to sensory experience.

Meanwhile, James McNeill Whistler challenged traditional representation with his evocative painting Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1872), prioritizing mood and visual sensation over form. Even earlier, Georgiana Houghton created “spirit drawings” composed of abstract shapes—an extraordinary precursor to abstraction, especially considering she exhibited them publicly in 1871, long before abstraction was formally recognized.

Expressionism and the Emotional Canvas

Expressionist painters pushed boundaries with bold brushwork, exaggerated forms, and intense color palettes. Their emotionally charged works were reactions to modern life and a rejection of the more restrained styles of late 19th-century painting. Artists like Edvard Munch and James Ensor, influenced by Post-Impressionism, shifted the focus from external subjects to internal states of being—an essential step toward abstraction.

Paul Cézanne, though rooted in Impressionism, sought to reconstruct reality through simplified forms and modulated color. His vision of reducing nature to geometric shapes—cubes, spheres, and cones—laid the foundation for Cubism, a movement that would redefine visual language.

Mysticism and the Geometry of Spirit

In Eastern Europe, the late 19th century saw a surge of mystical and spiritual philosophies that deeply influenced early abstract artists. Theosophist Madame Blavatsky inspired pioneers like Hilma af Klint and Wassily Kandinsky, who infused their work with symbolic geometry and metaphysical meaning.

Thinkers like Georges Gurdjieff and P.D. Ouspensky also shaped the spiritual underpinnings of abstraction, influencing artists such as Piet Mondrian, Kasimir Malevich, and František Kupka. Their work explored the unseen, the universal, and the eternal—transcending the material world through form and color.

Early 20th Century: Fauvism, Cubism, and the Breakthrough

At the dawn of the 20th century, a group of vibrant young artists—Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, André Derain, Raoul Dufy, and Jean Metzinger—shocked the Paris art scene with wild, expressive use of color and form. Critics dubbed their movement Fauvism, and its raw energy directly influenced Kandinsky’s journey into abstraction.

Simultaneously, Cubism emerged, driven by Cézanne’s geometric vision. Artists like Braque and Pablo Picasso began deconstructing objects into basic shapes, challenging the very notion of perspective and representation. Together, Fauvism and Cubism opened the door to a new visual language—one that no longer relied on depicting the visible world.

The Birth of Pure Abstraction

In 1912, at the Salon de la Section d'Or, František Kupka unveiled Amorpha, Fugue in Two Colors, a groundbreaking abstract painting. Poet Guillaume Apollinaire coined the term Orphism to describe this new art form—one that built visual structures from elements created entirely by the artist, rather than borrowed from nature. It was, as he described, “pure art.”

This period saw a flurry of cross-cultural exchange. Artists from Paris, Munich, and Moscow shared ideas through exhibitions, manifestos, and publications. The Russian avant-garde, including David Burliuk, embraced Cubism and sought to rival the German Der Blaue Reiter group. The interconnectedness of these movements fueled a rich diversity of abstract styles.

Between 1909 and 1913, artists across Europe were experimenting with abstraction:

• Francis Picabia painted Caoutchouc, The Spring, and The Procession, Seville

• Kandinsky created Untitled (First Abstract Watercolor), Improvisation 21A, and Picture with a Circle

• Kupka developed his Orphist works including Discs of Newton and Amorpha

• Robert Delaunay explored color and motion in Simultaneous Windows and Formes Circulaires

• Léopold Survage envisioned abstract cinema with Colored Rhythm

• Piet Mondrian began his journey with Tableau No. 1 and Composition No. 11

Constructing the Future: Suprematism and Neo-Plasticism

By 1914–1915, Henri Matisse was nearing pure abstraction with works like French Window at Collioure, View of Notre-Dame, and The Yellow Curtain. Meanwhile, Russian artists Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov developed Rayism, using lines like beams of light to construct dynamic compositions.

In 1915, Kasimir Malevich unveiled Black Square, a stark, revolutionary work that marked the birth of Suprematism—a movement focused on pure feeling through geometric form. Liubov Popova, another Suprematist, created her Architectonic Constructions and Spatial Force Constructions, pushing abstraction into spatial and architectural realms.

From 1915 to 1919, Piet Mondrian refined his abstract language of horizontal and vertical lines, filled with rectangles of primary color. This became the foundation of Neo-Plasticism, a philosophy shared by the De Stijl group, including Theo van Doesburg, which aimed to reshape not just art, but the entire built environment.

Russian Avant-Garde: Art as Life, Art as Spirit

In early 20th-century Russia, a radical transformation in artistic philosophy gave rise to the Constructivist movement. Artists no longer saw art as a distant, decorative pursuit—it was to be embedded in everyday life. Vladimir Tatlin famously declared, “Art into life!”, a rallying cry for Constructivists who believed the artist should become a technician, mastering the tools and materials of modern industry.

Figures like Varvara Stepanova and Alexandre Exter abandoned traditional easel painting in favor of theatre design, graphic arts, and functional aesthetics. Their work reflected a belief that art should serve society, not merely adorn it.

Yet not all Russian avant-garde artists embraced this utilitarian vision. Kazimir Malevich, Anton Pevsner, and Naum Gabo championed a more spiritual approach. For them, art was a means of exploring the human condition and creating a sense of individual place in the cosmos. Their work sought transcendence rather than utility.

During this fertile period, Russian artists collaborated with Eastern European peers such as Władysław Strzemiński, Katarzyna Kobro, and Henryk Stażewski, forming a vibrant network of experimentation and exchange.

As political pressures mounted, many artists who resisted the materialist view of art fled Russia. Pevsner relocated to France, Gabo moved through Berlin and England before settling in America, and Wassily Kandinsky, after studying in Moscow, joined the Bauhaus in Germany. By the mid-1920s, the revolutionary freedom of the post-1917 era had faded, and by the 1930s, socialist realism became the only officially sanctioned style.

Music and the Spiritual Dimension of Abstraction

As visual art grew more abstract, it began to echo the qualities of music—an art form built on rhythm, tone, and time rather than representation. Kandinsky, an amateur musician himself, was deeply inspired by the idea that color and form could resonate like musical notes, stirring the soul.

This concept wasn’t new. Charles Baudelaire had suggested that all senses respond to stimuli in interconnected ways, and that art could tap into a deeper aesthetic unity. Kandinsky and others took this further, believing that abstract art could transcend everyday experience and reach a spiritual plane.

The Theosophical Society played a key role in popularizing Eastern philosophies and mystical teachings in Europe. Artists like Hilma af Klint, Piet Mondrian, and Kandinsky explored the occult not as superstition, but as a pathway to creating “inner objects”—visual expressions of universal truths. Geometry became sacred: circles, squares, and triangles were not just shapes, but timeless symbols of cosmic order.

🏛️The Bauhaus: Unity of Art and Craft

Founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius in Weimar, Germany, the Bauhaus revolutionized art education. Its philosophy was simple yet profound: unify all visual and plastic arts—from architecture and painting to weaving and stained glass—into a cohesive whole.

Rooted in the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement and the Deutscher Werkbund, the Bauhaus emphasized functionality, craftsmanship, and interdisciplinary collaboration. Its faculty included luminaries such as Paul Klee, Johannes Itten, Josef and Anni Albers, László Moholy-Nagy, and Kandinsky himself.

In 1925, the school moved to Dessau. But as the Nazi regime rose to power, the Bauhaus was forced to close in 1932. By 1937, avant-garde art was labeled “degenerate” in the infamous Entartete Kunst exhibition. This triggered a mass exodus of artists—not just from the Bauhaus, but from Europe itself. Many fled to Paris, London, and America, carrying the Bauhaus legacy with them.

Abstraction in Paris and London: A New Constellation

During the 1930s, Paris became a sanctuary for artists escaping political oppression across Europe. Russian, German, Dutch, and Polish artists converged, bringing with them a rich diversity of abstract styles.

Sophie Tauber and Jean Arp collaborated on organic-geometric sculptures and paintings. Katarzyna Kobro applied mathematical principles to her sculptural work, pushing abstraction into new dimensions.

This convergence led to efforts to categorize and understand the many emerging styles. The Cercle et Carré group, organized by Joaquín Torres-García and Michel Seuphor, hosted an exhibition featuring 46 artists—including Kandinsky, Pevsner, and Kurt Schwitters. Though criticized by Theo van Doesburg for its lack of clarity, it sparked a deeper dialogue. Van Doesburg responded by launching the journal Art Concret, which defined abstract art as a pure reality of line, color, and surface.

In 1931, the group Abstraction-Création was founded to provide a more inclusive platform for abstract artists. As political tensions escalated in 1935, many artists regrouped in London, where the first exhibition of British abstract art was held.

In 1936, Nicolete Gray organized the Abstract and Concrete exhibition, showcasing works by Piet Mondrian, Joan Miró, Barbara Hepworth, and Ben Nicholson. Hepworth, Nicholson, and Gabo later moved to St. Ives, Cornwall, where they continued their Constructivist explorations in a new coastal context.

Late 20th Century: Abstraction Finds a New Home

As the political climate in Europe darkened during the 1930s, many avant-garde artists fled to the United States, seeking refuge from the rise of fascism. By the early 1940s, New York had become a vibrant melting pot of modernist movements—Expressionism, Cubism, Surrealism, Dada, and Abstraction—all represented by exiled European masters such as Marcel Duchamp, Fernand Léger, Piet Mondrian, Jacques Lipchitz, André Masson, Max Ernst, and André Breton.

These artists brought with them a wealth of cultural influence, which was absorbed and reinterpreted by emerging American painters. The relative freedom of the New York art scene allowed experimentation to flourish. Galleries that had once focused solely on European art began to recognize the talent of local artists, many of whom were beginning to mature into distinct voices.

One such voice was Piet Mondrian, whose Composition No. 10 (1939–1942) exemplified his radical yet classical approach to abstraction—primary colors, white ground, and black grid lines forming a visual language of pure geometry. Meanwhile, Georgia O’Keeffe, though often associated with modernist abstraction, remained a maverick—creating deeply personal, highly abstract forms without aligning herself with any particular movement.

The Rise of Abstract Expressionism

As American artists explored abstraction in diverse ways, they began to form cohesive stylistic communities. The most influential of these was the Abstract Expressionists, also known as the New York School. In the post-war atmosphere of New York, dialogue and collaboration thrived. Artists and educators like John D. Graham and Hans Hofmann served as bridges between the European modernists and the younger generation of American creators.

Mark Rothko, born in Russia, began with surrealist imagery before transitioning into his iconic color fields—large, luminous blocks of pigment that evoked deep emotional resonance. Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, and Franz Kline emphasized the physical act of painting itself, turning gesture into meaning. Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning evolved from figurative work into full abstraction by the end of the 1940s.

New York had become the epicenter of modern art, drawing artists from across the United States and around the world. The city’s energy, openness, and intellectual ferment made it the ideal environment for abstraction to thrive.

21st Century: Expanding the Language of Abstraction

As the 20th century progressed into the 21st, abstraction continued to evolve in new and unexpected directions. Movements such as Color Field Painting, Lyrical Abstraction, Post-Painterly Abstraction, Minimalism, Op Art, and Neo-Dada expanded the vocabulary of non-representational art.

The rise of Digital Art introduced entirely new mediums and possibilities, while Hard-Edge Painting, Geometric Abstraction, and Monochrome Painting refined the visual language of form and color. Assemblage and Shaped Canvas Painting challenged the boundaries of traditional formats, merging sculpture and painting into hybrid expressions.

In the United States, the concept of Art as Object gained prominence, particularly in the Minimalist sculptures of Donald Judd and the bold, structured paintings of Frank Stella. These works emphasized material, space, and form over emotional or symbolic content.

At the same time, Lyrical Abstraction brought a sensuous, expressive use of color to the forefront. Artists such as Robert Motherwell, Patrick Heron, Kenneth Noland, Sam Francis, Cy Twombly, Richard Diebenkorn, Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, and Veronica Ruiz de Velasco infused their work with emotion, spontaneity, and a deep engagement with the physicality of paint.