John Marin

Castorland New York, 1913

Uragano, 1944

Weehawken-Sequence, 1916

Bear Flag Rebels, 1934

Bryant Square, 1932

Spring, 1953

Tunk Mountains, Autumn, Maine, 1945

The Sea, 1964

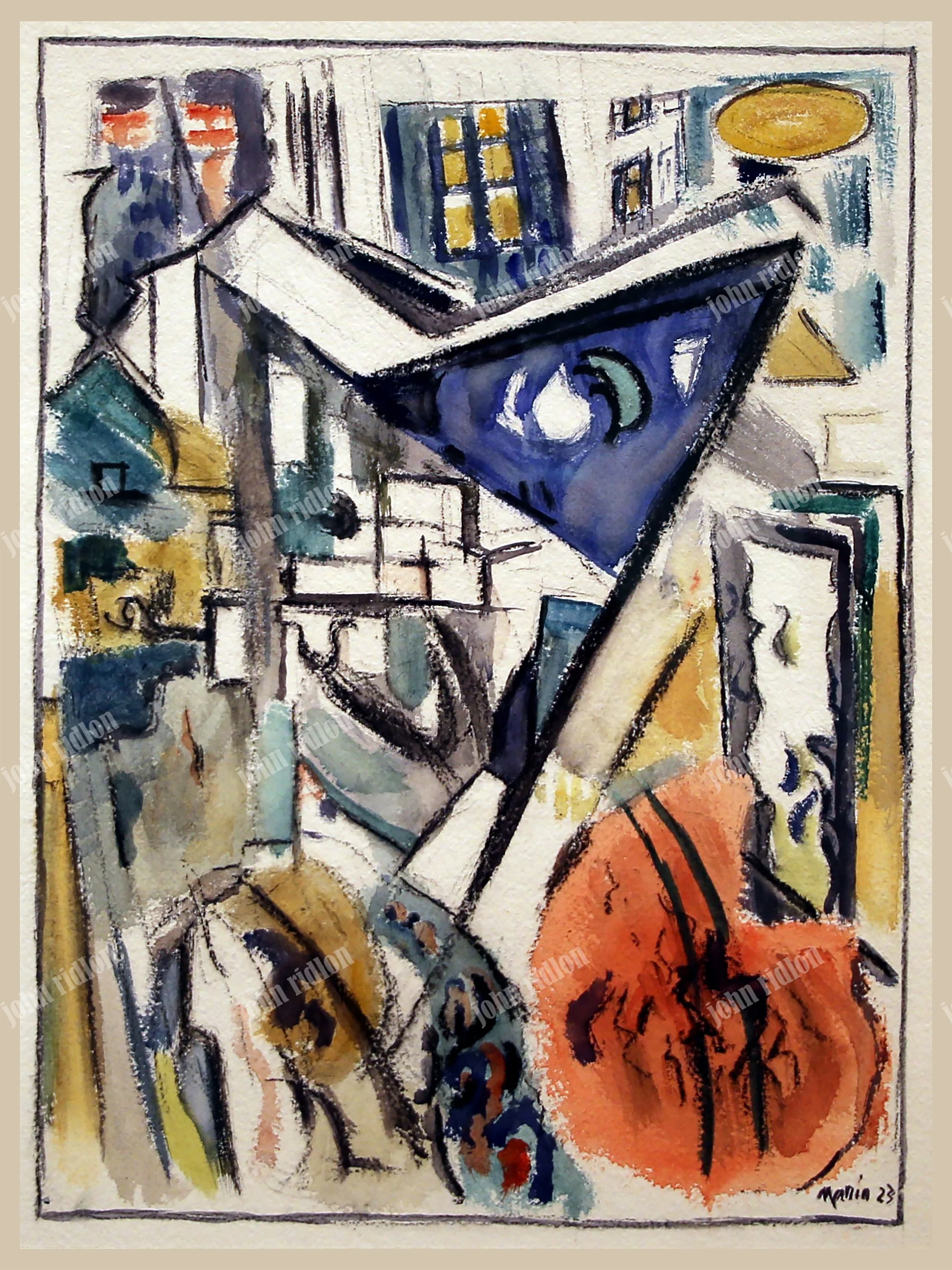

Lower Manhattan, 1923

Lower Manhattan 2, 1920

Astrazione, 1917

The Blue Sea, 1964

John Marin

In 1948, a Look magazine survey of museum directors, curators, and critics named John Marin the greatest painter in the United States. It was a remarkable recognition for an artist whose early life gave little hint of such acclaim. Until nearly forty, Marin drifted between careers—working in a wholesale notions house, training as an architect in New Jersey, and studying intermittently at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Art Students League in New York. But through all the uncertainty, one constant remained: drawing. “I just drew,” Marin said. “I drew every chance I got.”

That compulsion to draw was the heartbeat of Marin’s art. It carried him through a formative period in Paris from 1905 to 1909, where he made etchings of European architecture for the tourist trade. But it was in 1908, at the Salon d’Automne, that modernist photographer Edward Steichen saw Marin’s watercolors and was struck by their vitality. Steichen arranged for Marin’s first exhibition at 291 Gallery, the epicenter of modern art in New York. A few months later, Alfred Stieglitz—the gallery’s visionary founder—took Marin under his wing.

The Stieglitz Years: Watercolor as Modernism

When Marin returned to the U.S. in 1909, and permanently in 1910, he quickly established himself as a cutting-edge modernist. His work appeared annually at Stieglitz’s succession of galleries—291, The Intimate Gallery, and An American Place—for most of his career. Stieglitz championed Marin’s use of watercolor, a medium often dismissed as less serious than oil. But Marin’s gestural watercolors of New York’s architecture and Maine’s rugged coastlines became some of the most admired works in Stieglitz’s orbit.

Marin settled in Cliffside, New Jersey, where he kept his studio for most of the year. Beginning in 1914, he and his wife Marie, along with their son John Jr., spent summers in Maine. Critics praised his watercolors in newspapers and magazines, and collectors sought them with growing fervor. Though Marin also painted in oil, it was watercolor that defined him.

“Fewer strokes, still fewer strokes. Fewer strokes must count. A full mellow ring to each stroke,” he wrote to Stieglitz in 1916—a mantra of economy and resonance.

Drawing as Gesture, Drawing as Thought

Marin’s devotion to drawing was not just technical—it was philosophical. From childhood, he drew constantly, both for pleasure and for purpose. He used drawing to record what he saw, test visual ideas, and work out compositions for paintings and prints. In rural places like Maine, he often skipped preliminary sketches, painting watercolors directly on site. But in New York, where the bustle made easel work impossible, he sketched on the move.

“The drawings,” Marin said, “were mostly made in a series of wanderings around about my City—New York—with pencil and paper in—short hand-writings as it were—Swiftly put down.” He used cheap 8 x 10-inch writing pads, bought in bulk, and filled piles of sketchbooks that he consulted in his studio. These drawings weren’t architectural renderings—they were energetic notations of motion and force, capturing the pulse of buildings, crowds, and city rhythms.

“Drawing is the path of all movements Great and Small,” he wrote. “Drawing is the path made visible.”

The Heroic Years and Artistic Maturity

By the 1930s, Marin’s reputation had soared. In 1936, the Museum of Modern Art honored him with a one-man retrospective. That same year, Alfred Stieglitz died, but Marin continued to work with Stieglitz’s widow at An American Place. He remained in New Jersey, summered in Maine, and kept painting with undiminished passion.

His late works—especially Composition VIII, IX, and X—were monumental statements. They balanced firm structure with playful, almost Baroque flourishes, reflecting the relaxed wisdom of an artist in his final chapter. In canvases like Capricious Forms, Marin let his shapes dance with abandon, while works like Two, Etc. reminded viewers of the disciplined elegance of his Bauhaus-influenced years.

Even in his most whimsical moments, Marin’s work remained balanced, structured, and deeply intentional. Titles like Rigid and Bent, Reduced Contrasts, Serenity, and Moderation reflected the paradoxes he explored—freedom within form, emotion within geometry.

Legacy on the Shore

John Marin died in 1953 on the rocky shore of Cape Split, Maine. His work is held in major collections across the country, including the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts and the Colby College Museum of Art, which houses the largest archive of his paintings, drawings, and photographs.

Marin’s legacy is not just in his technique, but in his philosophy. He taught us that watercolor could be bold, that abstraction could be emotional, and that drawing was not just a tool—but a way of seeing, a way of moving through the world.

To explore Marin’s work and other pioneers of abstraction, visit masterworksprints.com.

A Short Biography

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.