Post-Impressionism

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh: A Life in Paint

He signed his work simply “Vincent.” No surname, no flourish—just a first name, as if to say: I am one of you. That gesture alone tells us something profound. Van Gogh didn’t paint to impress. He painted to connect. His art doesn’t belong to one era or one audience. It moves across time, across borders, across lives. Whether you’re standing in front of a canvas or reading one of his letters, you feel it—that pulse of emotion, that urgency to be understood. His brushwork is not decoration. It’s declaration.

Van Gogh’s paintings are not just visual—they’re visceral. They speak in the language of texture and color, of longing and light. They remind us that feeling is not weakness, and that beauty often comes from brokenness. In every stroke, there’s a question: Do you see what I see? Do you feel what I feel?

And in that exchange, we find something rare. Something real.

A Short Life, A Long Echo

Vincent died in 1890, just 37 years old. A gunshot wound. A final silence. And yet, his voice never stopped speaking. He had spent ten years chasing recognition—critical, financial, emotional. It came too late. But the world caught up. And once it did, it couldn’t let go. His story became legend. The tortured genius. The lonely visionary. But myth can be a veil. To truly see Van Gogh, we must strip away the icon and return to the man. To the letters he wrote to Theo. To the canvases he filled with wheat fields, stars, and sorrow.

He lived in a time of upheaval—industrialization, shifting beliefs, new ways of seeing. Photography was changing how we captured reality. Japanese prints were reshaping composition. Van Gogh absorbed it all, but he didn’t imitate. He translated. He understood that vision isn’t just optical—it’s emotional. We don’t just see with our eyes. We see with our hearts.

That’s why his work still speaks. It’s not about history. It’s about humanity.

The Artist and the Mirror

Van Gogh didn’t separate art from life. He painted what was around him—but more importantly, he painted what was within him. His work is autobiography in color. His letters are confessionals in ink.

Unlike Gauguin, who sought escape in distant lands, Van Gogh stayed close to home—close to the soil, the sky, the people. He began in the tradition of Realism, but he broke through its boundaries. Inspired by the Impressionists, he used paint not just to record, but to reveal. Emotion became his medium.

He didn’t chase perfection. He chased truth.

The Northern Years: Holland and England

In the beginning, there was mud and mist. Van Gogh’s early years unfolded in the rural landscapes of Holland, where he sketched laborers, farmers, and weavers with a reverence that bordered on spiritual. These were not idealized figures. They were real people—tired, dignified, enduring.

He traveled through France, Belgium, England, and the Netherlands, always drawn to the lives of the ordinary. His palette was muted, his lines rough. But the honesty was radiant. These works weren’t just images. They were acts of empathy.

He didn’t paint for praise. He painted to bear witness.

A Restless Beginning

From an early age, Vincent van Gogh carried the quiet intensity of someone slightly out of step with the world around him. He was solitary by nature—more comfortable wandering the fields alone than playing with other children. He had a keen eye for detail, a gift for languages, and a remarkable ability to recall images and impressions with vivid clarity.

Later in life, Van Gogh would describe his childhood as “gloomy, cold and sterile.” He often clashed with his family and was remembered by a household servant as peculiar and withdrawn—more like an old soul than a boy. Yet in solitude, he found peace. He roamed the flat landscapes of Brabant, absorbing the subtle shifts in light and season, attuned to the quiet poetry of the countryside.

Nature as Companion

The Van Gogh family lived in a small village far removed from the noise of industrial life. It was a farming community, sustained by crops like potatoes, rye, and buckwheat. To the south and west stretched open heathland, dotted with pine groves and marshes. This was Vincent’s world—one shaped by weather, rhythm, and change. For someone as sensitive as he was, the land was never static. It breathed, evolved, and whispered.

Walking was essential to him. Whether through fields, towns, or cities, the act of moving through space was central to his being. His surroundings left deep impressions, and his visual memory was astonishing. People, places, books, and objects stayed with him, resurfacing in letters and paintings years later. “There will always remain in us something of the Brabant fields and heath,” he wrote to his brother Theo. Even during one of his final illnesses, he recalled in detail the rooms of his childhood home in Zundert—the garden, the churchyard, the neighbors, even the magpie’s nest in the tall acacia tree.

Like his artistic hero Jean-François Millet, Van Gogh was drawn to the cycle of the seasons—a metaphor for the human journey from birth to death. As the son of a pastor in a farming village, he would have known the biblical verse from Genesis: “While the earth remaineth, seedtime and harvest, and cold and heat, and summer and winter, and day and night shall not cease.” That rhythm echoed through his life and work.

School Days and Separation

Vincent’s formal education began at the local school, but his parents soon withdrew him, fearing that rough play with village boys was having a negative influence. He was placed under the care of a governess, and at age eleven, sent to Jan Provily’s boarding school in Zevenbergen.

It was a difficult transition. In letters written years later, he revisited the moment his parents left him behind—describing how he stood on the steps, watching their carriage disappear down a rain-soaked road, flanked by sparse trees and mirrored puddles. The scene, etched in his memory, reveals one of Van Gogh’s greatest gifts: the ability to fuse emotional experience with precise visual detail, creating images that linger long after the moment has passed.

After two years, he transferred to a state-run boarding school in Tilburg. There, he excelled in languages—French, English, and German—and began formal drawing lessons, a subject woven into the curriculum. But his time at school ended abruptly. Just before his fifteenth birthday, in March 1868, he was withdrawn for reasons that remain unclear, though financial hardship is likely. His formal education ended there.

The Young Apprentice: Vincent’s First Steps into the Art World

After leaving school, Vincent van Gogh spent a quiet year at home, uncertain of his path. It was his uncle Cent—his godfather and a respected figure in the art trade—who intervened. Though the Van Gogh family had long been steeped in religious tradition, with many members entering the church, Vincent was steered toward a different calling: the art business, following in the footsteps of three uncles who had built careers in the trade.

In July 1869, Vincent began work at Goupil & Co., a prominent French firm with a branch in The Hague. Goupil specialized in high-quality reproductions—etchings, engravings, and photographs—representing the popular artists of the day, including Salon painters and members of the Barbizon school. These artists, though often dismissed by the avant-garde, were widely admired by the public. Among them were Jean-François Millet and Théodore Rousseau, whose depictions of rural life and landscapes deeply influenced Vincent’s emerging sensibility.

Millet’s reverence for the peasant’s labor and Rousseau’s spiritual portrayal of nature struck a chord in Vincent. He saw in their work a quiet dignity, a connection between humanity and the land. Rousseau’s The Footbridge (1855), with its gentle composition and pastoral harmony, offered a vision of nature as sanctuary—a theme Vincent would later transform into something more raw, more expressive, and more personal.

Letters as Lifelines

Vincent’s years at Goupil were marked not only by professional growth but by the deepening of his bond with his younger brother, Theo. Their correspondence—over 600 letters in total—would become one of the most intimate and revealing archives in art history. Vincent wrote with honesty and urgency, describing his thoughts, his struggles, and his evolving artistic vision in language that was both simple and poetic.

Though he also wrote to his parents and sister Wilhelmina, it was Theo who received the full weight of Vincent’s inner life. In his letters, Vincent described colors as if they were emotions, landscapes as if they were memories. He signed off with a phrase that never changed: “Always your loving brother, Vincent.” His final, unfinished letter to Theo was found in his pocket after his death.

A Promising Start

At Goupil’s, Vincent proved himself a capable and well-liked employee. He developed a close relationship with the manager, Herman Tersteeg, and even made illustrated booklets for Tersteeg’s daughter—filled with drawings of animals, birds, and insects. Though his social life was quiet, he filled his evenings with scrapbooks of engravings and reproductions, and occasionally met with artists like Anton Mauve, who would later marry Vincent’s cousin.

By 1872, Vincent’s future seemed bright. That summer, he visited his family in Helvoirt, where his father had taken a new parish. Theo joined him there, and the two brothers spent long hours walking through the countryside. During one of these walks, they made a pact—to support each other and write regularly. That promise would last for the rest of Vincent’s life.

London Calling

In 1873, Vincent was promoted to Goupil’s London office, a prestigious post in the heart of the city’s West End, just steps from the National Gallery. The branch was expanding into original contemporary art, though its tastes remained conservative. Vincent’s role focused on handling and selling reproductions and engravings, and he was thrilled by the opportunity. “I am looking forward very much to seeing London,” he wrote to Theo. “It will be splendid for my English.” Meanwhile, Theo had joined the firm as well, first in Brussels and then back in The Hague, taking over Vincent’s former position. The brothers were now united not only by blood and letters, but by a shared profession—one that would shape their lives in ways neither could have imagined.

The Young Professional

Vincent van Gogh arrived in London in 1873 with a top hat on his head and hope in his heart. To all appearances, he was a rising young art dealer—ambitious, well-mannered, and eager to make his mark. He had earned a solid reputation during his years at Goupil’s office in The Hague and now held a respectable salary, four times that of the average London laborer. His lodgings were modest but pleasant, and his days were filled with work, walks, and wonder.

London dazzled him. Its grandeur and grit, its parks and alleyways, its galleries and gas lamps—all stirred something deep within. He was captivated by the spectacle of Hyde Park’s Rotten Row, where elegant riders paraded on horseback. A friend once remarked that Vincent, while appearing to stare at nothing, seemed to absorb everything.

He immersed himself in English art and literature. At the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, he gravitated toward narrative and sentiment—praising the works of Millais, Constable, and Turner. He read Keats to improve his English and admired the poet’s romanticism and melancholy. But it was the English Social Realists—Fildes, Holl, Herkomer—who truly moved him. Their depictions of poverty, illness, and aging resonated with his growing sense of moral urgency.

A City of Contrasts

London was not just a city of galleries and gardens—it was also a place of shadows. Van Gogh became fascinated by the engravings in illustrated magazines like The Graphic and Illustrated London News. These woodblock prints, sharp and immediate, captured the raw realities of urban life. He collected them obsessively, preferring early editions when the lines were still crisp. “The impressions I got on the spot were so strong,” he wrote, “the drawings are clear in my mind.”

He also discovered London: A Pilgrimage, a book by Blanchard Jerrold with haunting illustrations by Gustave Doré. The images—crowded tenements, foggy alleys, and stark contrasts of light and dark—left a lasting impression. Van Gogh saw in these works not just artistry, but empathy. “An artist needn’t be a clergyman,” he wrote, “but he must have a warm heart for his fellow men.”

A Private Heartbreak

The Brixton Affair

In August 1873, Van Gogh moved to Brixton, a quiet suburb in south London. His new landlady, Ursula Loyer, ran a small school with her daughter Eugenie. Vincent was deeply touched by their bond, writing to Theo, “I never saw or dreamed of anything like the love between her and her mother.”

Over time, his admiration for Eugenie turned into love. He confessed his feelings, unaware that she was already engaged. She rejected him, gently but firmly. Vincent, devastated, refused to let go. His persistence made it impossible to remain in the house, and he and his sister Anna—who had come to London seeking work—were forced to move out.

Though he tried to mask the pain, the experience left a deep scar. He wrote to Theo that he and Eugenie had agreed to “consider ourselves each other’s brother and sister,” but the heartbreak lingered. Years later, he would describe this episode as the beginning of “many years of humiliation.”

His parents sensed something was wrong. “Living at the Loyers’ with all those secrets has done him no good,” his father wrote. His mother, more tenderly, told Theo, “Poor boy, he does not take life easily.”

A Shift in Spirit

The emotional fallout from Brixton bled into Vincent’s professional life. His enthusiasm for selling art waned. He turned inward—toward religion, books, and reflection. In a letter to Theo, he quoted Ernest Renan:

This choice of words reveals a turning point. Van Gogh was no longer content to be a salesman. He was beginning to search for something deeper—for purpose, for meaning, for a way to serve humanity through The Inner Life: What We Can Never Fully Know

The connection between an artist and their work is never simple. Art doesn’t explain a life, nor does a life fully explain the art. In Vincent van Gogh’s case, the relationship between his inner world and his creative output is especially complex—intensely personal, yet ultimately unknowable. We can trace patterns, read letters, and study his brushwork, but the true nature of his inner life remains elusive. What we do know is that Van Gogh’s art and his emotional landscape were deeply intertwined. His paintings weren’t just expressions of vision—they were acts of survival.

Paris: A City of Light and Shadows

In 1874, Van Gogh’s life took another turn. Concerned by his growing instability, his uncle Cent arranged for him to transfer from Goupil’s London office to the company’s Paris headquarters. Vincent resented the move and withdrew from his family, refusing to write for months. When he returned to London briefly, his depression lingered, and he was soon recalled to Paris once more.

At first, the city overwhelmed him. But as he wandered its streets and museums, his resistance softened. He spent hours at the Louvre and the Musée du Luxembourg, drawn to works that echoed his own spiritual and emotional intensity. He admired Charles Gleyre’s Lost Illusions, Georges Michel’s Rembrandtesque landscapes, and Daubigny’s Spring. But it was Rembrandt’s Supper at Emmaus that held him in awe—a painting he saw not just as art, but as revelation.

Despite his immersion in the city’s artistic offerings, Van Gogh seemed unaware of the seismic shifts happening around him. The Impressionists had just held their first exhibition, but their radical approach didn’t register in his letters. Instead, he gravitated toward the moral gravity of painters like Corot and Jules Breton, whose sentimental depictions of rural life aligned with his own values.

Evangelism and Obsession

During this period, Van Gogh’s religious fervor intensified. What had once been a source of comfort became an obsession. His letters grew dense with biblical references, often alienating those closest to him. He urged Theo to abandon the works of writers like Michelet and Renan, whom he had once admired, and embraced a rigid, ascetic lifestyle.

He lived in a modest room in Montmartre—his “little cabin”—sharing it with Harry Gladwell, an English colleague who encouraged his spiritual pursuits. In the evenings, they read Dickens, George Eliot, and above all, the Bible. Vincent denied himself meat and other pleasures, believing that sacrifice was the path to truth.

His admiration for Jean-François Millet deepened. At a sale of Millet’s drawings, he wrote to Theo, “I felt like saying, ‘Take off your shoes, for the place where you are standing is Holy Ground.’” For Van Gogh, art and faith were inseparable—both sacred, both redemptive.

A Bitter Departure

By the end of 1875, Van Gogh’s behavior had become increasingly erratic. He took leave from work during the busiest season to spend Christmas with his family in Etten. Upon returning to Paris, he was summoned by Léon Boussod, soon to be the company’s director. After nearly seven years at Goupil’s, Vincent was pressured to resign.

His uncle Cent expressed “bitter sorrow,” while his father described the situation as “a shame and a scandal.” Vincent’s professional life had unraveled, and his personal life was no less turbulent.

A Return to England—and a Search for Purpose

Religion now dominated Van Gogh’s thoughts. A brief return to England offered a glimmer of hope. He taught in schools in Kent and London, but never found stability. Back in Etten, his family convened to discuss his future. His father suggested opening a gallery. Theo encouraged him to pursue art. But Vincent ignored their advice. Instead, he applied to become an evangelist in the coal-mining regions of northern England. When that failed, he considered missionary work in South America. He was searching—not for success, but for meaning.

A Wandering Soul: Ramsgate to Amsterdam

As Van Gogh’s time at Goupil came to an end, a new opportunity emerged—one that offered a temporary reprieve from professional disappointment. In April 1876, he accepted a teaching post at a small school in Ramsgate, a coastal town in southeast England where his sister Anna was living. Before leaving Paris, he purchased three etchings after Millet—an artist whose moral gravity and reverence for rural life continued to shape Van Gogh’s worldview.

The Kentish countryside reminded him of home. In letters, he described the sea views and coastal drama with quiet affection. Drawing became a kind of therapy—his way of managing the emotional turbulence that never seemed far away. He sketched the landscape and his surroundings, sending modest, amateur drawings to his family as visual postcards of his new life.

London Again: Teaching and Empathy

After a brief probationary period in Ramsgate, Van Gogh followed the school to London in July 1876. But the move offered little promise. Once again, he found himself adrift and searching. He soon accepted a position as an assistant teacher at a Methodist boys’ school in Isleworth, on the outskirts of the city, run by Reverend Jones.

His salary was modest—£15 a year—and his duties included collecting school fees from families in London’s East End. “That very poor part which you have read about in Dickens,” he wrote to Theo. These encounters deepened his empathy for the working class and the marginalized. The city’s contrasts—its grandeur and its poverty—left a lasting impression.

Van Gogh’s fascination with London was shaped in part by London: A Pilgrimage, a book illustrated by Gustave Doré. Its dramatic black-and-white engravings captured the city’s chaos and beauty, its spiritual weight and social despair. Van Gogh treasured the book, and its visual language would echo in his own later work.

A Voice in the Pulpit

Though he never aligned himself with a single denomination, Van Gogh remained deeply involved in church life. He was thrilled to be invited to preach at the Congregational Church in Turnham Green, west London. His chosen text, Psalm 119—“I am a stranger on the earth; hide not Thy commandments from me”—reflected his own sense of exile and yearning.

In his sermon, he spoke of life as a pilgrimage, of sorrow and solitude as pathways to redemption. “We are strangers on the earth,” he said, “but though this be so, yet we are not alone, for our Father is with us.” These themes—grief, humility, spiritual longing—would remain central to his art and life.

Homeward Bound: A New Direction

Once again, Van Gogh’s position offered no future. He returned to the Netherlands, determined to pursue a life of service. His family, concerned but divided, debated his next steps. Uncle Cent arranged for him to work as a clerk in a bookshop in Dordrecht.

Books, for Van Gogh, were nearly as vital as paint. “I have a more or less irresistible passion for books,” he wrote, “and I want to continually instruct myself, to study, just as much as I want to eat bread.” Literature became his window into the lives of others—a way to understand humanity from the inside out.

A Practical Christian

In Dordrecht, Van Gogh’s religious fervor intensified. He fasted, prayed obsessively, and deprived himself of sleep. His behavior grew erratic. He arrived late to work, spent hours reading instead of clerking, and unnerved his landlord with long prayers and nocturnal study sessions. “Out of his mind,” the landlord said.

Van Gogh immersed himself in spiritual texts, especially The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis. He copied the entire book by hand and kept a drawing of the saint in his room. Its teachings—on humility, sacrifice, and service—aligned with his own ideals. “Never be entirely idle,” the text urged, “but either be reading, or writing, or praying, or meditating, or endeavoring something for the public good.” Van Gogh took these words to heart.

Amsterdam: A Final Attempt

In 1877, Van Gogh moved to Amsterdam to pursue theological studies. He lived with his Uncle Johannes, a vice-admiral, in a house overlooking the docks. Before he could enroll at the university, he needed to learn Greek and Latin—an academic hurdle that proved insurmountable. “I feel my head heavy,” he wrote, “and often it burns and my thoughts are confused.” He struggled with the coursework and grew increasingly disillusioned. His letters began to reject the art trade and the bourgeois values of his family. “I would rather eke out a living,” he wrote, “than fall into the hands of Messrs. Van Gogh.”

After just three months, it was clear the path to ministry through formal education was closed. A schoolteacher friend shared his concerns with the family, and after another round of consultations, it was agreed: Vincent would leave Amsterdam and seek a new way to fulfill his calling.

A Practical Christian: The Gospel of Suffering

During his time in Amsterdam, Van Gogh’s religious devotion deepened into something more intense—more consuming. He lived with a sense of moral urgency, chastising himself for perceived failures and embracing physical discomfort as a form of penance. Mendes de Costa, a Jewish academic and contemporary, recalled Van Gogh walking across the square without a coat in winter, punishing himself for not preparing his lessons well enough. “Don’t be mad at me, Mendes,” he said one day, “I’ve brought you some little Van Gogh’s spiritual life was not confined to prayer—it was woven into his daily habits, his reading, and his art. He copied passages from Cours de Dessin, a self-help drawing manual, throughout his life, and visited the newly opened Rijksmuseum, where he studied the works of Rembrandt, Frans Hals, and Ruysdael. What struck him most was their immediacy—their confidence in the first stroke. “They did not retouch very much,” he wrote. This spontaneity would later become a hallmark of his own style, echoed in the Japanese prints he began collecting around this time.

The Borinage: A Gospel in Action

In 1879, Van Gogh found himself in the coal-mining region of the Borinage in southern Belgium. He had failed to gain entrance to university and had been rejected from formal missionary training. But the Church offered him a temporary post—an unofficial chance to preach among the poor.

Here, he tried to live as Christ might have: giving away his possessions, sleeping on straw, wearing a tattered army coat, and smearing coal dust on his face to resemble the miners. He tended to the sick, visited the dying, and spoke of redemption through suffering. “I shall have to suffer much,” he wrote to Theo, “especially from those peculiarities I cannot change—my appearance, my way of speaking, my clothes.” But his zeal unsettled the Church. After six months, they withdrew their support, citing his “almost scandalous excess of zeal.” Madame Bonte, the wife of a local pastor, remembered him saying, “They turned me out like a dog… because I tried to relieve the misery of the wretched.”

A Turning Point: Salvation in Art

After his dismissal, Van Gogh moved to the nearby village of Cuesmes. He lived with a miner’s family in cramped conditions and began to draw seriously. In the bitter winter of 1880, at his lowest point, he set out on foot to visit Jules Breton, the painter of peasant life whom he deeply admired. The journey took nearly a week. But when he arrived, he found not a humble farmhouse, but a grand brick studio. Overwhelmed and disheartened, he turned back, trading sketches for food and shelter along the way.

Yet something shifted. “In these depths of misery,” he wrote, “I felt that I shall get over it somehow. I shall set to work again with my pencil… and from that moment I have had the feeling that everything has changed for me.”

At 27, Van Gogh chose his path—not as a preacher of words, but as an evangelist in paint. Like Émile Zola, whose novel Germinal depicted the brutal lives of miners, Van Gogh sought to reveal the dignity and suffering of ordinary people. But unlike Zola’s fatalism, Van Gogh’s vision was pantheistic, rooted in compassion and the belief that beauty could emerge from hardship.

His figures would always be tied to their land, their labor, their light. Just as the skies in Dutch landscapes are inseparable from the soil below, Van Gogh’s people belonged to the territory they inhabited. His art would not romanticize—it would bear witness.

Destitute but Free

Though his health was failing and his finances nonexistent, Van Gogh had found clarity. He was free to draw and paint, and he did so with obsessive focus. In October 1880, he moved to Brussels to study anatomy and perspective—determined to build the technical foundation for the expressive vision he had begun to uncover.

This was not the end of his suffering. But it was the beginning of his art.

Brussels: A Student of Feeling

By early 1881, Van Gogh had committed himself to becoming an artist—but the path was far from stable. He was living in Brussels, studying anatomy, perspective, and the expressive power of line and form. He visited galleries, copied prints, and immersed himself in the works of Rubens, whose dynamic compositions and emotional depth helped Van Gogh begin to understand how art could move beyond description into revelation.

Theo, now thriving in the art trade, began sending Vincent regular financial support—a lifeline that would continue for the rest of Vincent’s life. Their relationship was complex: Vincent depended on Theo emotionally and financially, yet often resented the imbalance. In two letters from January 1881, he first accused Theo of neglect, then quickly apologized. This tension—between gratitude and frustration—echoes throughout their correspondence.

A Kindred Spirit

Through Theo’s connections, Van Gogh met Anthon van Rappard, a young aristocratic artist. Though cautious at first, the two became close friends. Van Rappard invited Vincent to share a studio, and together they worked intensely. Van Gogh produced powerful drawings like The Lamp Bearers and Miners’ Women Carrying Sacks—works shaped by his time in the Borinage and his admiration for English illustrators. But when Van Rappard left Brussels in April, Vincent felt adrift. Without his friend’s companionship, the city lost its appeal. He returned to Etten, seeking comfort in familiar landscapes and the rhythms of rural life.

Studying the Masters

Van Gogh’s reverence for the Dutch masters deepened. He admired Frans Hals for his bold, spontaneous brushwork and Rembrandt for his spiritual gravity and mastery of light and shadow. These artists, he felt, painted not just faces but souls. Their work challenged him to create a modern equivalent—art that could speak to the human condition with honesty and depth.

Portraiture, for Van Gogh, became a kind of history painting for his own time—a way to document not events, but emotions.

Becoming “Vincent”

By now, Van Gogh had shed his former identity. His faith in the institutional Church had collapsed, and his commitment to art had become absolute. To mark this transformation, he began signing his work simply “Vincent.” It was a symbolic break from the Van Gogh family name—a gesture of independence, and perhaps a nod to Rembrandt, who also signed his work with only his first name.

Etten: A Return and a Reckoning

Back in Etten, Van Gogh’s health improved. He painted outdoors, reconnecting with the land and the people. He embraced the idea that truth—however harsh—was rooted in rural life. “When I say I am a painter of peasant life, that is a fact,” he wrote. His evenings spent with miners, weavers, and peat cutters had shaped his vision. He found kinship in the work of Millet, Breton, Lhermitte, and Mauve, and in the Dutch tradition of Rembrandt and Hals. Yet his spiritual independence remained fierce. “Their whole system of religion is horrible,” he wrote to Theo, rejecting the moral rigidity of his upbringing.

Another Wound

During the summer of 1881, Van Gogh fell in love again—this time with his widowed cousin, Kee Vos-Stricker. She was visiting Etten with her young son. Vincent declared his feelings, but Kee rejected him outright. Undeterred, he pursued her, even traveling to Amsterdam to plead his case. Her father refused to let him see her. In a dramatic moment, Vincent placed his hand over a flame and said, “Let me see her for as long as I can keep my hand in the flame.” The lamp was extinguished. He was told, “You shall not see her.” His mother sided with Kee. From that moment, Vincent considered her a stranger. Kee vanished from his letters, and the emotional rupture was permanent.

Painting in Earnest

Unable to remain at home, Van Gogh moved to The Hague. He lived in poverty on the industrial outskirts of the city, but he was free—and determined. He began painting seriously, visiting Anton Mauve for guidance and continuing to refine his technique. For the next 18 months, he worked obsessively, laying the foundation for the expressive style that would soon emerge.

Père Millet: A Prophet in Paint

To Van Gogh, Jean-François Millet was more than a painter—he was a spiritual guide. Revered as the “peasant-painter,” Millet embodied the values Van Gogh longed to inherit: humility, reverence for labor, and a deep connection to the land. “Millet is father Millet,” Van Gogh wrote, “counsellor and mentor in everything to the younger painters.” His religious fervor, once channeled through sermons, now found expression in brushstrokes. Art had become his gospel.

The Hague: A Style Begins to Emerge

In The Hague, Van Gogh began to paint in earnest. With guidance from his cousin Anton Mauve and the help of instructional manuals, he developed a style that was raw, awkward, and unmistakably his own. He worked obsessively with pen and ink, chalk, and litho crayon—tools that echoed the engravings he had collected from English periodicals. His empathy for the poor and working class fueled his vision, and his powers of observation gave his drawings a stark immediacy.

He struggled with perspective, a challenge for any artist depicting the flat Dutch landscape. To solve this, he built a simple drawing frame inspired by Albrecht Dürer and the old Dutch masters. It allowed him to break down scenes into geometric patterns, turning what once felt like “witchcraft” into a tool of expressive clarity. Perspective, once elusive, became part of his visual vocabulary.

Drawing the City: A New Kind of Realism

Commissioned by his Uncle Cor to document the changing face of The Hague, Van Gogh produced a series of pen and ink drawings that rejected picturesque convention. He avoided tourist landmarks, focusing instead on roadworks, poor neighborhoods, and the people who lived there. “Full reality,” he called it.

These works, rooted in the visual language of magazine illustration, marked the beginning of Van Gogh’s mature style. His character studies were powerful and unsentimental—figures rendered with empathy but without romanticism. The strong, chiseled lines and dramatic tonal contrasts gave his subjects a dignity that transcended their circumstances. These were not portraits of individuals—they were archetypes of human endurance.

Sien: Love, Loss, and the Mater Dolorosa

Van Gogh’s emotional life was no less intense than his artistic one. Early in his time in The Hague, he met Clasina Maria Hoornik—known as Sien—a seamstress, artist’s model, and prostitute. She was 32, pregnant, and struggling with serious health issues. Van Gogh saw in her both suffering and salvation.

“I need a woman,” he wrote to Theo. “I cannot, I may not live without love.” Sien moved in with him, bringing her young daughter. Van Gogh gained not only a model and companion, but a surrogate family. He justified the relationship through his moral and religious convictions, describing her as “pure, notwithstanding her depravity,” and likening her expression to Delacroix’s Mater Dolorosa.

But the relationship was fraught. His family disapproved, and tensions came to a head on Christmas Day 1882, when Van Gogh refused to attend church. His father demanded he leave the house. Van Gogh did so immediately, returning to Sien and the life he had chosen.

Sorrow: An Icon of Human Pain

The fallout was swift. Mauve, once a mentor, severed ties. Tersteeg, a former supporter, withdrew his friendship. Van Gogh was isolated, ill, and financially strained. In June 1882, he was hospitalized with gonorrhoea. Sien cared for him, and soon after, gave birth to her second child.

Their relationship defies easy categorization. Sien was lover, muse, mother figure, and symbol. Van Gogh saw in her the embodiment of suffering—and of grace. His drawing Sorrow, created shortly before she moved in, captures this duality. A solitary figure, bowed and anonymous, paired with a single word: “Sorrow.” It is one of the most haunting images in Western art, echoing medieval woodcuts and anticipating the emotional intensity of Munch, Kollwitz, and Picasso.

Family Pressure and the Final Break with Sien

As winter approached in 1883, Van Gogh’s depression deepened. He wrote to Theo of a growing emptiness—“a kind of void” that nothing could fill. The emotional weight of his relationship with Sien, coupled with financial strain and family disapproval, became unbearable.

Under pressure from his family, Van Gogh returned to Nuenen, where his parents had relocated. He arrived to suspicion and disgrace. Though he insisted he was not the father of Sien’s child, it’s likely his family didn’t believe him. The details of their separation remain unclear, but by autumn, Sien had resumed her former life.

Years later, her body was found in the Rotterdam docks—a tragic end that echoed the fate of many women in 19th-century art and literature. For Van Gogh, she had been muse, companion, and symbol. Her loss marked a turning point.

Drenthe and the Search for Solitude

In September 1883, Van Gogh left The Hague and moved to the remote province of Drenthe in northeast Holland. The countryside offered cheaper living and a retreat from personal turmoil. He hoped the marshy landscapes, with their low cottages and endless horizons, might reflect his inner world and artistic ambitions.

At first, he worked alongside friends Breitner and Van Rappard, but they soon departed, leaving Van Gogh alone. His paintings from this period are steeped in melancholy—documents of isolation that, despite their bleakness, offer a kind of spiritual solace. Yet the solitude proved too heavy, and after two months, he returned to Nuenen. “A thing I was loath to do,” he confessed to Theo.

His father, now pastor of the parish, welcomed him cautiously. Van Gogh set up a studio in the laundry room and began again.

Nuenen: A Rural Renaissance

From December 1883 to November 1885, Van Gogh entered one of his most prolific phases, producing nearly a quarter of his surviving works. He embraced a coarse, unpolished technique that matched his vision of rural authenticity. “This is who I am,” he wrote, “as real as the people and landscape I paint.”

He rejected refined materials—using thick graphite instead of pastels, rough paper instead of smooth—and avoided “nice colors.” His art reflected his emotional state: isolation, loss of faith, and a widening gap between him and his father. These themes are especially present in his cemetery scenes, such as Funeral in the Snow near the Old Tower and Churchyard in Winter, painted in December 1883.

Van Gogh turned away from the modern city and toward the land, aligning himself with French Realists like Courbet and Millet. He sought subjects that could embody the dignity of labor and the rhythm of nature.

Progress and Despair

Van Gogh’s anxiety about his technical limitations haunted him. “I have no technique,” he wrote—but over time, he came to see this as a strength. His lack of academic polish allowed for emotional immediacy. “Nature has reproduced herself through me in a kind of shorthand,” he said. “Let our work be so clever that it seems naïve.”

Despite his self-doubt, Van Gogh was clear-eyed in assessing his progress. He described sitting before a scene, painting it, feeling disappointed, and returning later to find a faint echo of the original vision. That echo, he believed, was enough.

Tragedy and Transformation

In late 1884, Van Gogh’s depression returned. He lashed out at Theo: “You haven’t sold a thing I’ve done… you haven’t even tried.” Though unfair, the outburst revealed growing confidence in his work.

Around this time, he became involved with Margot, an older woman who fell in love with him. The relationship was fraught. When she believed an engagement was imminent and it failed to materialize, she attempted suicide by drinking strychnine. She survived, but was institutionalized.

Then, in March 1885, Van Gogh’s father died unexpectedly. Despite their differences, he had always supported Vincent, even if he couldn’t understand him. “If only he succeeds in some way,” he had written days before his death.

Van Gogh was devastated. He quarreled with his sister Anna and moved out of the family home, taking lodgings with the sexton of the local Catholic church. Despite the turmoil, he continued to work, even entertaining the idea of forming an artists’ cooperative—though it never materialized.

Influences and Emerging Style

Van Gogh’s oil paintings from this period reveal the influence of Rembrandt and Jozef Israëls, a Dutch member of the Barbizon school. His figures are sculptural—emerging from darkness into light, carved by bold outlines and dramatic tonal shifts. They are not just representations—they are revelations.

This was Van Gogh’s art in transition: rooted in realism, shaped by sorrow, and reaching toward something transcendent.

The Weavers: Threads of Labor and Suffering

In the rural district surrounding Nuenen, Van Gogh turned his attention to the weavers—men hunched over looms in dim cottages, their bodies shaped by the rhythm of work and the weight of poverty. Inspired by his friend Anthon van Rappard and novels like George Eliot’s Felix Holt, the Radical, Van Gogh saw in these figures a visual and moral truth.

He described one loom as “a monstrous black thing of grimed oak—like some fabled instrument of torture, a prison.” His drawings and paintings from this period echo the monumental dignity of Millet’s peasants, but with a sculptural intensity that borders on distortion. These were not idealized workers—they were broken, bent, and real.

A Modern Masterpiece: The Potato Eaters

In the summer of 1885, Van Gogh set out to create his first deliberate masterpiece. He had been reading Delacroix, absorbing ideas about the emotional power of color. “A certain power of color is awakening in me,” he wrote to Theo, “stronger and different than what I have felt till now.”

Encouraged by Van Rappard’s visit and praise for his drawings, Van Gogh began work on The Potato Eaters—a secular Last Supper, a modern Supper at Emmaus. He chose the de Groot family as his models, paying them modestly and sketching each figure in preparation. But complications arose: Gordina de Groot became pregnant, and Van Gogh was rumored to be the father. The local priest forbade Catholics from posing for him.

Despite the scandal, the painting was completed. Van Gogh sent a lithograph to Van Rappard, hoping for support. Instead, his friend called it “a violence to nature.” Devastated, Van Gogh ended their five-year friendship. Theo, however, saw its power: “Some see beauty in it,” he wrote, “precisely because the characters are so genuine.” Van Gogh replied, “I feel a power within me to do something… my work holds its own.”

Truth in Art: Still Life with Bible

Before leaving Nuenen, Van Gogh painted Still Life with Bible—a symbolic farewell to his past. The family Bible lies open to Isaiah: “He is despised.” Beside it sits Émile Zola’s bleak novel La Joie de Vivre. The juxtaposition is stark: faith and realism, tradition and modernity.

Van Gogh revered the French novelists for their unflinching portrayal of life. “If one wants the truth,” he wrote to his sister, “life as it is… then there are Zola, de Goncourt, and so many others who satisfy our need for being told the truth.”

Color and Music: A New Sensibility

Delacroix’s writings led Van Gogh to explore the emotional resonance of color—its ability to evoke mood, like music. He compared color harmonies to Wagner’s symphonies and even took piano lessons, though briefly. His unconventional approach—shouting “Prussian blue!” or “bright cadmium!” as he struck the keys—was too much for his teacher. But the idea stuck: color was not just visual—it was emotional, musical, spiritual.

Antwerp and the Academy: A Break and a Beginning

In November 1885, Van Gogh walked to Antwerp, leaving Holland behind for good. “More estranged from them than if they were strangers,” he wrote of his family. He rented a small room above a paint shop and enrolled at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts.

The Academy was prestigious, but Van Gogh found its methods lifeless. “It is correct… but it is dead,” he wrote. He stood out—arriving in a cattle-driver’s smock and fur hat, crashing into the institution like a storm. With no female models available, he joined outside classes, where his bold, anatomical drawings began to attract attention. “A woman must have hips, buttocks, a pelvis in which she can carry a baby!” he declared, rejecting the sanitized academic ideal.

Despite the hardship and isolation, Antwerp marked a turning point. Van Gogh studied Rubens, admiring his color and composition, but found him “superficial” compared to Rembrandt, whom he revered as the “great and universal master.” His Dutch heritage remained a source of pride—and a compass for his evolving identity.

Antwerp: Rubens and the Awakening of color

In Antwerp, Van Gogh encountered the grandeur of Peter Paul Rubens—Baroque painting at its most sensual and theatrical. Rubens’ mastery of flesh, movement, and light left a lasting impression. In Van Gogh’s Portrait of a Woman with Red Ribbon (1885), a cabaret singer emerges in creamy tones reminiscent of Rembrandt, but it’s the vivid flashes of red and green—borrowed from Rubens—that hint at a new expressive force. The energy that would later explode across his canvases is here restrained, but unmistakably present.

At the Cathedral of Our Lady, Van Gogh studied Rubens’ The Raising of the Cross and The Descent from the Cross. He absorbed the dynamic brushwork, the luminous skin tones, the rippling mane of a horse, and the emotional weight of the compositions. “color,” he wrote, “is not everything in a picture, [but] it is what gives it life.” Rubens confirmed what Van Gogh had read in Delacroix: “True drawing is modelling in color.” That idea would become a cornerstone of his art.

Though he admired Rubens’ theatricality, Van Gogh’s gaze was shifting. He began to think more deeply about portraiture—not as flattery, but as revelation. His paintings from this time show a new expressive potential beginning to stir.

Paris: color as Emotion

In Paris, Van Gogh immersed himself in the works of Delacroix and Monticelli—two artists who treated color not as decoration, but as emotion. He visited churches and galleries, standing before Delacroix’s Pietà and the murals at Saint Sulpice, especially Jacob Wrestling with the Angel. There, he studied the drama of interlocked figures, the landscape’s intensity, and the still life at the painting’s edge—a quiet explosion of color and form that would echo in Van Gogh’s own work.

Monticelli: A Forgotten Visionary

Van Gogh was captivated by Adolphe Monticelli, a painter from Marseille whose richly encrusted canvases shimmered with prismatic color. Though Monticelli had fallen into obscurity, Van Gogh saw in him a kindred spirit. “I sometimes think I am really continuing that man,” he wrote. Monticelli’s impasto-heavy surfaces, his romantic subjects, and his disregard for convention inspired Van Gogh to embrace freedom and intensity in his own technique. Van Gogh encouraged Theo to promote Monticelli’s work, and the admiration he held for this eccentric artist was one of the driving forces behind his later decision to travel south to Provence.

Painting Flowers: A Laboratory of Color

In the summer of 1886, Van Gogh began painting flowers—over 30 canvases survive from this period, each a study in color, contrast, and composition. Like self-portraits, flower paintings required no model. They offered freedom: the chance to experiment with radical juxtapositions—blue against orange, red against green, yellow against violet.

He described Monticelli’s flower pieces as “an excuse for gathering together in a single panel the whole range of his richest and most perfectly balanced tones.” Van Gogh’s own descriptions are lyrical, but never indulgent. Beneath the beauty lies a rigorous exploration of harmony and intensity. “I have made a series of color studies,” he told Levens, “simply flowers… seeking oppositions… trying to render intense color and not a grey harmony.” His brushes were loaded, his canvases unprimed, his process direct and urgent. He painted without underdrawing, letting color lead the way.

This burst of activity was further ignited by the eighth Impressionist exhibition, which opened in May 1886. Van Gogh was absorbing everything—technique, theory, emotion—and transforming it into something entirely his own.

The Starry Night, 1889

The Night Cafe, 1888

The Arena, 1888

Café Terrace at Night, 1888

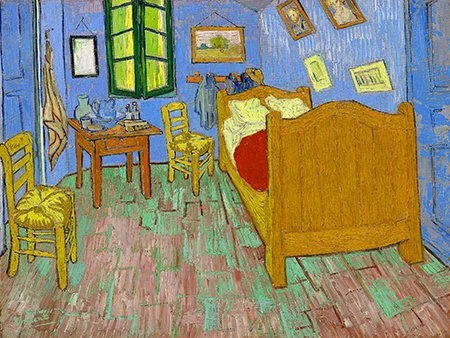

Bedroom in Arles, 1889

The Siesta, 1890

The Red Vineyard, 1888

Stairway at Auvers, 1890

Sheaves of Wheat, 1890

Sunflowers Roses, 1886

Lilacs, 1889

Farms near Auvers, 1890

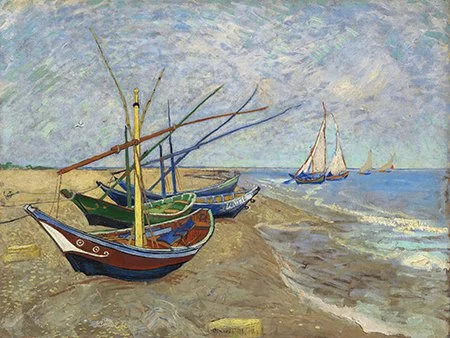

Fishing Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries, 1888

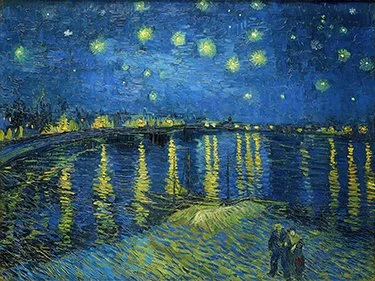

Starry Night Over the Rhône, 1888

Street in Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890

Vase with Red Poppies, 1886

Vase with Pink Roses, 1890

Almond Blossom, 1890

Blossoming Acacia Branches, 1890

Sunflowers, 1887

Irises, 1889

Imperial Fritillaries in a Copper Vase, 1887

Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin: From Impressionist Apprentice to Symbolist Visionary

Paul Gauguin stands as one of the most influential figures in the transition from Impressionism to the more introspective and symbolic currents of modern art. Though initially trained in the Impressionist tradition—with its focus on fleeting light and everyday scenes—Gauguin soon grew disillusioned with its limitations. By the late 1880s, as Impressionism reached its peak, he began to explore bolder color theories and decorative compositional strategies that would lead him toward Symbolism.

His brief but intense collaboration with Vincent van Gogh in Arles marked a turning point. The summer they spent painting side by side in the vivid light of southern France was both creatively fertile and emotionally volatile. Shortly afterward, Gauguin distanced himself not only from Van Gogh but from Western society altogether. Having already left behind a career as a stockbroker, he embarked on a radical journey—both geographic and philosophical—that would take him to the South Pacific and reshape his artistic identity.

In Tahiti and other parts of French Polynesia, Gauguin developed a distinctive style that fused direct observation with spiritual and mythic symbolism. His work drew heavily on the so-called “primitive” arts of Africa, Asia, and Oceania—not as mere aesthetic borrowings, but as vehicles for expressing deeper truths about existence, nature, and the soul. His rejection of European norms—family, career, and the Parisian art establishment—has since become emblematic of the artist as a seeker, a mystic, and a visionary outsider.

Artistic Achievements and Philosophical Pursuits

Gauguin’s early mastery of Impressionist techniques laid the foundation for his later innovations. He immersed himself in the study of color theory and visual perception, influenced by contemporary scientific research into how the eye processes light and form. His travels through Brittany, the Caribbean, and Polynesia exposed him to diverse landscapes and spiritual traditions, which he absorbed into a new artistic language.

This evolution culminated in what he called synthetic painting—a style that prioritized symbolic meaning over realistic depiction. Gauguin’s canvases became meditations on life’s fundamental questions: What is the nature of existence? Can art offer spiritual insight or a path to harmony with the natural world? His work often reflected a yearning for purity and transcendence, inspired by the perceived authenticity of non-Western cultures.

As a leading figure in the late 19th-century movement known as Primitivism, Gauguin helped shape a European fascination with cultures untouched by industrialization. Though the term is now viewed critically, it once captured a romantic belief that such societies were more spiritually attuned and emotionally sincere than their Western counterparts. Gauguin’s art embodied this ideal, even as it grappled with the contradictions and complexities of cross-cultural representation.

Legacy of Liberation and Artistic Autonomy

By the time Gauguin severed ties with his wife, children, and the European art world, he had fully embraced a life of radical independence. His name became synonymous with the idea of artistic freedom—of breaking away from societal expectations to pursue a personal, often solitary, vision. That legacy endures today, not only in the luminous canvases he left behind but in the myth of the artist as wanderer, rebel, and truth-seeker.

Gauguin’s journey was never just about aesthetics. It was a philosophical quest, a spiritual rebellion, and a profound reimagining of what art could be. His work continues to challenge and inspire, inviting us to look beyond surface appearances and into the symbolic depths of color, form, and cultural meaning.Gauguin’s Portraits: A Mirror of the Self and the World

Paul Gauguin’s multifaceted career—as painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, and writer—remains one of the most compelling chapters in the history of modern art. His work is marked by a restless pursuit of authenticity and transcendence, a desire to escape the confines of Western civilization and uncover deeper truths through art. While his landscapes and depictions of Tahitian life have long been celebrated, his portraiture—arguably one of the most psychologically charged and symbolically rich aspects of his oeuvre—has remained curiously underexamined. This oversight is particularly striking given the central role portraiture played in Gauguin’s artistic and philosophical evolution.

Portraiture as Psychological and Mythic Terrain

To understand Gauguin’s portraits is to enter a labyrinth of self-invention, cultural appropriation, and metaphysical inquiry. Unlike traditional portraitists who sought to capture likeness or social status, Gauguin used portraiture as a vehicle for introspection and myth-making. His sitters—whether friends, lovers, or imagined figures—often appear as archetypes or spiritual avatars rather than individuals. Their features are stylized, their expressions enigmatic, their settings infused with symbolic resonance. Gauguin’s portraits are less about the external world and more about the internal cosmos—his fears, desires, and philosophical musings rendered in pigment and form.

This approach reflects Gauguin’s broader rejection of realism and embrace of synthétisme, a style that prioritized emotional and symbolic content over naturalistic representation. His portraits often blur the boundaries between subject and symbol, merging the sitter’s identity with allegorical motifs drawn from religion, mythology, and non-Western cultures. In this way, Gauguin’s portraiture becomes a mirror—not just of the self, but of the world as he wished to reimagine it.

Cultural Hybridity and the Ethics of Representation

Gauguin’s travels to Brittany, Martinique, and ultimately Tahiti were driven by a desire to escape the perceived decadence of European society and reconnect with a more “primitive” mode of existence. This quest, however, was fraught with contradictions. While he sought authenticity, he also projected romanticized and often distorted visions onto the cultures he encountered. His portraits of Tahitian women, for instance, are imbued with sensuality and mysticism, but they also reflect colonial fantasies and orientalist tropes.

Yet Gauguin’s engagement with non-Western cultures was not merely decorative. He immersed himself in local traditions, studied indigenous art forms, and incorporated their visual languages into his work. His portraits often feature flattened perspectives, bold outlines, and symbolic color schemes reminiscent of Polynesian tapa cloths or Buddhist iconography. These elements reflect a syncretic aesthetic—a fusion of Western and non-Western influences that challenged the conventions of academic art and anticipated the global turn in modernism.

Still, the ethical implications of Gauguin’s portraiture remain complex. His representations raise questions about cultural appropriation, gender dynamics, and the power of the gaze. Were his sitters collaborators in a shared artistic vision, or passive subjects of his imagination? Did his portraits honor their individuality, or subsume them into his personal mythology? These tensions continue to animate scholarly debates and shape our understanding of Gauguin’s legacy.

Dialogues with Tradition and Innovation

Despite his reputation as a rebel, Gauguin was deeply conversant with the history of Western art. His portraits often echo the compositional strategies of Renaissance masters, the psychological intensity of Romantic painters, and the formal innovations of his Impressionist peers. He admired Courbet’s realism, Degas’s intimacy, Manet’s modernity, and Cézanne’s structural rigor. These influences surface in his work through subtle quotations, stylistic borrowings, and thematic parallels.

Gauguin also maintained complex relationships with contemporary artists. His friendship with Vincent van Gogh, for example, yielded a series of portraits that reflect mutual admiration and rivalry. Gauguin’s depiction of Van Gogh painting sunflowers is both homage and critique—a portrait that captures the artist’s fervor while hinting at his instability. Similarly, Gauguin’s symbolic still lifes often function as surrogate portraits, evoking the presence of absent friends or artistic forebears through objects imbued with personal meaning.

His self-portraits are particularly revealing. Gauguin portrayed himself as Christ, devil, martyr, and visionary—roles that reflect his ambivalent self-image and his desire to transcend the mundane. These portraits are not mere records of appearance; they are existential statements, visual manifestos that assert his identity as a prophet of modern art.

The Catalogue and Its Contributions

The catalogue accompanying the exhibitions in Ottawa and London marks a watershed moment in Gauguin scholarship. Drawing on extensive international research, it offers the first comprehensive study of Gauguin’s portraiture, illuminating its aesthetic, cultural, and philosophical dimensions. Essays by leading scholars—including Elizabeth Childs, Dario Gamboni, Linda Goddard, Claire Guitton, Jean-David Jumeau-Lafond, and Alastair Wright—explore a wide range of topics, from Gauguin’s self-fashioning to his depictions of friends like Meijer de Haan.

The essays situate Gauguin’s portraits within the broader context of late nineteenth-century portraiture, a period marked by shifting notions of identity, representation, and artistic autonomy. They examine how Gauguin’s work responded to and reshaped these currents, offering new models of portraiture that fused personal symbolism with cultural critique. The catalogue also sheds light on lesser-known works, such as the recently discovered drawing of Jean Moréas for La Plume, revealing the depth and diversity of Gauguin’s portrait practice.

Legacy and Resonance

Ultimately, Gauguin’s portraits invite us to reconsider what it means to depict a person. They challenge the notion of fixed identity, suggesting instead that the self is fluid, multifaceted, and shaped by memory, myth, and desire. His portraits are not mere likenesses; they are acts of interpretation, constructions of meaning that reflect both the sitter and the artist.

This vision has had a profound impact on twentieth- and twenty-first-century art. From the psychological explorations of Expressionism to the conceptual interrogations of identity in contemporary portraiture, Gauguin’s influence continues to ripple across generations. His work reminds us that portraiture is not just about faces—it’s about stories, symbols, and the search for truth.

In the end, Gauguin’s portraits are mirrors—sometimes clear, sometimes clouded—that reflect the complexities of being human. They speak to the tensions between self and other, tradition and innovation, reality and imagination. And in doing so, they affirm the enduring power of art to illuminate the mysteries of existence.

Post-Impressionism

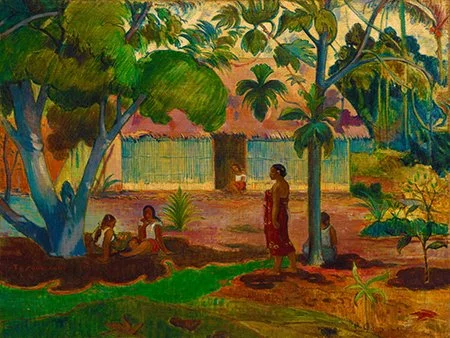

The Large Tree, 1891

The Month of Mary, 1899

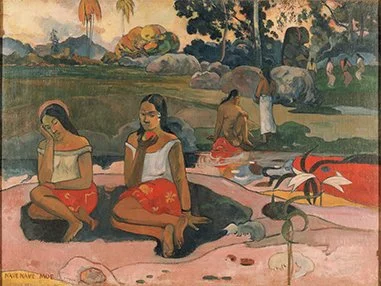

Nave Nave Moe, 1894

Portrait of Two Children, 1889

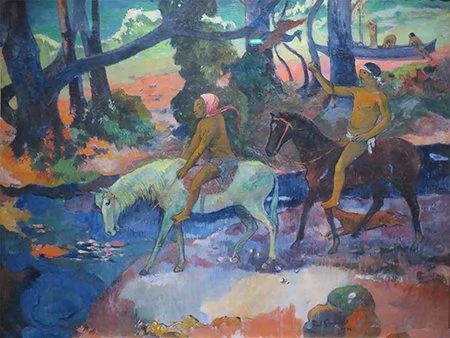

The Ford (The Flight),1901

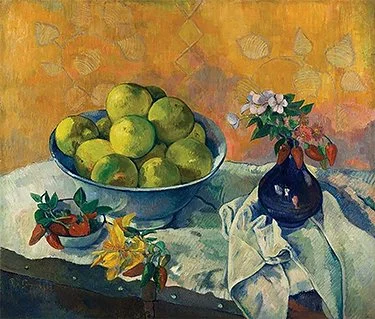

Still Life with Grapefruits, 1902

Still Life with Exotic Birds, 1902

Roses and Statuette, 1889

Still Life with Profile of Laval, 1886

Nafea Faa Ipoipo, 1892

Mrs Vornehme, 1896

Woman Holding a Fruit, 1893

Te Tiare Farani, 1891

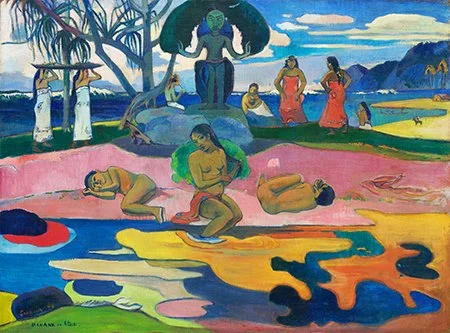

Mahana no Atua, 1894

Tahitian Pastorale, 1892

Boy on the Rocks, 1897

Post-Impressionism

Henri Rousseau

Fight between a Tiger and a Buffalo, 1908

Centennial of Independence (1892)

The Sleeping Gypsy (La Bohémienne endormie) (1897)

Myself Portrait Landscape, 1890

The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope (1905)

Tiger in a Tropical Storm, 1891

Virgin Forest with Sunset (1910)

The Dream, 1910

The Snake Charmer (1907)

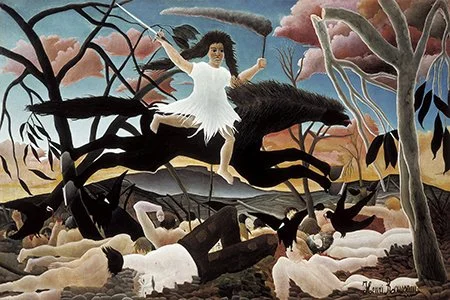

War, 1894

Henri Rousseau: The Dreamer of the Jungle

Henri Julien Félix Rousseau (1844–1910), affectionately nicknamed Le Douanier (“the customs officer”), was a French painter whose work defied convention and expectation. Though ridiculed in his lifetime for his lack of formal training, Rousseau became a beloved figure among avant-garde artists and is now celebrated as the archetype of the modern naïve painter—a visionary whose sincerity, imagination, and originality helped usher in new ways of seeing.

Early Life and Unlikely Beginnings

Rousseau was born on May 21, 1844, in Laval, a provincial town in northwestern France. The son of a tinsmith, he came from modest means and was a mediocre student. He left school early and entered military service in 1863, serving for four years. During this time, he met soldiers who had returned from France’s expedition to Mexico, and their vivid stories of tropical landscapes and exotic animals would later inspire some of his most iconic paintings.

After his father’s death in 1868, Rousseau moved to Paris to support his widowed mother. He married Clémence Boitard, with whom he had six children—only one survived. In 1871, he began working as a collector of the octroi, a municipal tax on goods entering Paris. This job earned him his famous nickname, Le Douanier, though he was never a customs officer in the strict sense.

Rousseau began painting seriously in his early forties. By age 49, he retired from his government post to pursue art full-time—a bold move for a man with no formal training and little recognition.

A Self-Taught Style: Naïve but Profound

Rousseau’s paintings are instantly recognizable: flat perspectives, bold outlines, vivid colors, and dreamlike compositions. He lacked academic training, and his work ignored traditional rules of proportion, depth, and anatomy. Critics mocked him, with one famously saying he “painted with his feet with his eyes closed.” But beneath the surface simplicity lay a profound originality.

His best-known works are lush jungle scenes, filled with wild beasts, exotic plants, and mysterious figures. Ironically, Rousseau never left France. His inspiration came from frequent visits to the Jardin des Plantes, the botanical gardens and zoo in Paris, as well as illustrated books and postcards.

His first major jungle painting, Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Surprised!), was exhibited in 1891 at the Salon des Indépendants. Though initially dismissed, it caught the attention of younger artists like Félix Vallotton, who praised its raw power. Over time, Rousseau’s work gained a cult following among avant-garde circles.

A Painter’s Painter: Admiration from the Avant-Garde

In March 1910, poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire wrote of Rousseau’s jungle painting Le Rêve:

Between 1905 and 1912, Rousseau’s idiosyncratic and seemingly “poorly painted” pictures achieved widespread recognition as significant contributions to modern painting. Young avant-garde artists in Paris—Félix Vallotton, Robert Delaunay, Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, and Wassily Kandinsky—engaged deeply with Rousseau’s work and publicly proclaimed their admiration. These artists helped elevate Rousseau from obscurity, recognizing him as a “painter’s painter”—someone whose work resonated first and foremost with fellow creators.

Félix Vallotton: Early Champion

When Rousseau exhibited Surpris!—his first jungle painting—in 1891, Vallotton published the first-ever positive review. In Le Journal Suisse, he wrote:

Vallotton’s praise was remarkable not only for its timing but for its insight. He recognized Rousseau’s independence and sincerity, anticipating Kandinsky’s later concept of “inner necessity.” Vallotton’s own paintings, such as Suzanne et les vieillards, show Rousseau’s influence in their constructed compositions, artificial lighting, and frozen action.

Forms of Admiration: Buying, Copying, Exhibiting

Esteem for Rousseau took many forms. Delaunay, Picasso, Kandinsky, Max Weber, and others purchased his work. Franz Marc copied one of his paintings. Artists like Vallotton, Léger, de Chirico, Beckmann, Frida Kahlo, and Diego Rivera created variations on Rousseau’s motifs.

American artist Max Weber exhibited Rousseau’s work at Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery in New York in 1910. Kandinsky and Marc included his paintings in the Blaue Reiter exhibitions of 1911. Delaunay organized a memorial exhibition of forty-seven paintings at the Salon des Indépendants in 1911 and arranged for Rousseau’s inclusion in the Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon in Berlin in 1913.

Robert Delaunay: Rousseau’s Champion

Delaunay first met Rousseau at the 1906 Salon des Indépendants, and they remained close until Rousseau’s death. Delaunay’s mother purchased La charmeuse de serpents, and Rousseau was invited to her salon, where he met Weber, Uhde, and the Steins.

Delaunay acquired more than a dozen of Rousseau’s paintings and drafted a monograph portraying him as a genius with precise aims. He wrote:

His painting La Ville de Paris (1912) paid homage to Rousseau by incorporating motifs from Moi-même: Portrait-paysage. In a 1913 letter to Marc, Delaunay described Rousseau’s work as “anti-descriptive,” “finished,” and “structured,” placing him on a level with the greatest Impressionists.

Fernand Léger: A Lasting Influence

Introduced to Rousseau in 1909 by Delaunay, Fernand Léger was permitted to watch him work. He later recalled:

Léger’s Le passage à niveau combines Cézanne’s depth with Rousseau’s bold lines and color fields. He borrowed motifs from Malakoff (1908), inserting a green locomotive where Rousseau had painted greenery. Rousseau’s anti-Impressionist clarity informed Léger’s work throughout his life. In Le mécanicien (1920), Léger constructed a mechanic from neutral color zones and machine elements, echoing Rousseau’s portraiture.

Kandinsky, Miró, Ernst: The Philosophical Legacy

Wassily Kandinsky acquired two Rousseau paintings and featured seven in the Blue Reiter Almanac, calling him the “father of a new total realism.” Kandinsky saw Rousseau’s simplicity as a counterpart to his own abstraction, both driven by “inner necessity.”

Joan Miró was drawn to Rousseau’s poetic narratives and unconventional picture planes. His early canvases reflect Rousseau’s garden-like compositions, where every element is subordinated to the flat surface.

Max Ernst shared Rousseau’s fascination with dreamlike landscapes. His techniques—grattage, frottage, and decalcomania—echo Rousseau’s method of transforming reality into phantasmagoric mystery. Both artists conjured vanished worlds, blending botanical precision with surreal fantasy.

Epilogue: A Century of Reverence

The extent to which Rousseau’s fellow artists committed to him is remarkable. Avant-garde figures like Picasso, Delaunay, Léger, and others brought about a complete reassessment of his work. Dealers such as Ambroise Vollard, Wilhelm Uhde, Joseph Brummer, and Paul Guillaume, along with critics and writers like Alfred Jarry, Apollinaire, and Arsène Alexandre, promoted his art long-term.

In 1911, Delaunay wrote:

Today, Rousseau’s reputation rests on the magical quality of his work. A century after his death, we still marvel at the magnetic pull of his paintings—their bold effectiveness, their enigmatic depths, and their enduring power to enchant.

Curtain and Fruit (1898)

The Fishermen, 1875

Picnic on a Riverbank, 1874

Roses in a Bottle, 1904

Rocks and branches (1895–1904)

Trees and Houses Near the Jas de Bouffan (1885–1886)

Abandoned House near Aix-en-Provence (1885)

A Village Road near Auvers, 1873

Four Bathers (Quatre baigneuses), 1877

Bathers (ca. 1890–1894)

Still Life with Bottle, Glass, and Lemons, 1868

Seated Peasant, 1896

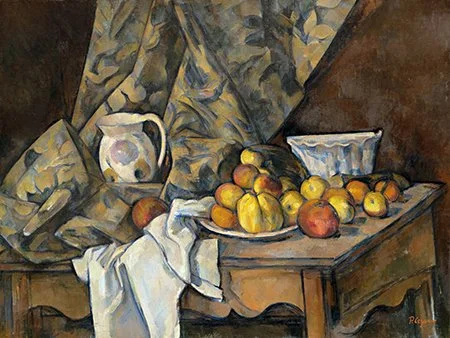

Still Life with Apples and Peaches, 1905

Auvers, Panoramic View (ca. 1873–1875)

The Bathers (ca. 1899–1904)

Still Life with Apples on a Sideboard, 1906

Dish of Apples, 1877

The Plate of Apples, 1887

Paul Cézanne's wife (1877)

Marie Cézanne's Sister (1866–1867)

Bathers (ca. 1874–1875)

Post-Impressionism

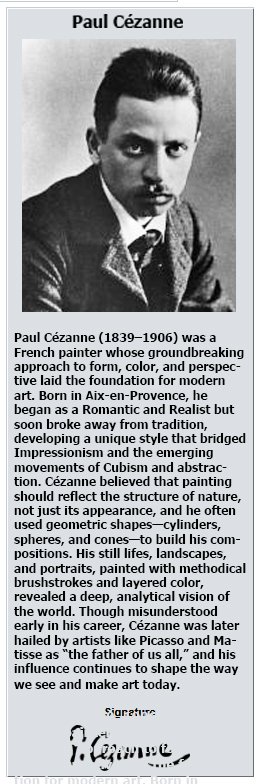

Cézanne in Context: Friendship, Influence, and the Making of a Legacy

Paul Cézanne was no recluse. In the 1860s and 1870s, he was actively engaged in Paris’s creative ferment—sharing ideas with progressive artists, musicians, writers, and critics. Admired even then as an “artist’s artist,” his influence on modern art has been thoroughly explored. Yet one aspect remains surprisingly underexamined: who collected his work, and which pieces they chose—especially leading up to his breakthrough 1895 exhibition at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery. These early collectors helped shape his legacy, a legacy we honor at Masterwork Prints by bringing timeless works into contemporary view.

The Cézanne most often quoted today is the one from his final decade, before his death in 1906. During this period, younger artists like Maurice Denis, Émile Bernard, and Paul Signac visited him, recorded their conversations, and later published their recollections. But these late reflections don’t necessarily reflect the ideas he shared with earlier peers—especially the Impressionists, whom he had known since arriving in Paris in 1861. Aside from a few letters to his childhood friend Émile Zola, now a celebrated novelist, we have limited direct insight into Cézanne’s early artistic philosophy.

Still, the Impressionists saw something profound in his work. Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro famously called him “the greatest of us all”—a sentiment reflected in how they treated his paintings. This essay traces Cézanne’s evolution and his impact on the Parisian avant-garde by exploring his connections to Zola’s literary circle and the artists who became his earliest and most devoted collectors. Their support—especially for works from the 1870s and early 1880s—was instrumental in his rise.

Defiant Beginnings: Cézanne, Zola, and the Art of Resistance

In his early career, Cézanne faced repeated rejection from the official Paris Salons. Rather than retreat, he responded with bold defiance—submitting provocative works that challenged convention. One jury member dismissed his technique as peinture au pistolet, claiming his brushwork looked as if it had been fired from a gun. Yet his friend, the artist Antoine Guillemet, saw this defiance as a mark of genius: “The less it looks like a painting, the closer one is to genius… Rejection at the Salon. Homeric struggle.”

The Artist as Character: How Cézanne’s Persona Shaped His Myth

Though Cézanne was known for his stubbornness and candor, his early battles with the Salon gained little traction—despite the dramatic way he framed his struggle. Writers in Zola’s circle, including Paul Alexis, Louis Edmond Duranty, and Marius Roux, recognized the theatrical potential in Cézanne’s persona and wove it into their fiction.

On May 30, 1870, art critic Théodore Duret wrote to Zola—already a prominent figure in Paris—requesting an introduction to the “completely eccentric” painter from Aix whose work had just been rejected by the Salon. Duret’s inquiry reflected Cézanne’s paradoxical status: obscure yet infamous. His notoriety had just been amplified by a caricature showing him defiantly holding two rejected paintings—a portrait of his friend Achille Empéraire and a now-lost nude. The caricature appeared alongside Cézanne’s first published interview, in which he declared, “I have very strong sensations.” That phrase would later become a rallying cry for younger artists who saw it as the essence of his pursuit: art that was raw, honest, and unfiltered. Before it became a mantra, however, writers like Zola interpreted it through their own lens, often using Cézanne as inspiration for fictional characters.

Parallel Ambitions: The Creative Bond Between Zola and Cézanne

Duret’s letter also reveals how well-known Cézanne’s friendship with Zola was during his early years in Paris. Zola replied that Cézanne wasn’t yet ready to show his work—a response consistent with his dual role as promoter and protector. But their relationship was more than that. Both men were ambitious outsiders in what Zola called la ville fiévreuse de Paris (the feverish city of Paris), and both were determined to surpass their idols—Balzac for Zola, Manet for Cézanne.

Cultivating the Myth: Cézanne, Zola, and the Art of Influence

Paul Cézanne wasn’t just painting in isolation—he was shaping a persona. In the 1860s, he introduced Émile Zola to artists who would later appear in Zola’s reviews and novels. Their friendship was more than personal; it was strategic. Cézanne’s defiance of the Salon jury wasn’t merely rebellion—it was part of a carefully crafted image. Five years earlier, Zola had dedicated his first novel, La Confession de Claude (1865), to Cézanne and their mutual friend Jean-Baptiste Baille. He even asked Marius Roux to review the book and mention Cézanne, then a student at the Académie Suisse. Roux described him as a modest, determined artist whose work always felt unfinished—a portrayal Zola echoed in later reviews and fictional characters.

Between Rebels and Refined: Cézanne at the Crossroads of Parisian Salon Culture

During his first decade in Paris, Cézanne remained a regular presence in Zola’s social circles. He attended Zola’s jeudis (Thursday gatherings) and was introduced to the bohemian salons of Nina de Villard—a flamboyant divorcée immortalized in Manet’s Lady with Fans (1874). Nina’s gatherings were famously anti-establishment, welcoming only those who defied bourgeois norms and academic recognition. Her guests included musicians, poets, and artists like Paul Alexis, Ernest Cabaner, Edmond de Goncourt, Stéphane Mallarmé, Manet, Paul Verlaine, and Dr. Paul Gachet. Paul Alexis later captured the wild energy of these evenings in his novel Madame Meuriot (1890).

On the opposite end of the social spectrum were the refined salons of Georges and Marguerite Charpentier, influential publishers of Zola, Flaubert, and the Goncourt brothers. Cézanne attended these events with Zola and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who became the Charpentiers’ unofficial portraitist after painting Marguerite and their children in 1878. While Impressionists were a minority at these gatherings, Cézanne’s presence—thanks to Zola—bridged both bohemian and bourgeois worlds.

Persona and Provocation: Cézanne’s Image in Artistic Circles

Despite frequent interactions with writers and critics, Cézanne saw little commercial success from those connections. One rare exception was art critic Théodore Duret, who sought him out in 1870 and later included three of his paintings in a 1894 collection sale. Ultimately, it was Cézanne’s deeper engagement with fellow artists—not literary figures—that led to more tangible rewards.

Between 1877 and 1878, Cézanne lived in the Batignolles neighborhood, near the cafés frequented by Édouard Manet and the younger artists who would later be grouped as Impressionists. At the Café de la Nouvelle Athènes, Manet reportedly welcomed Cézanne warmly, according to writer Georges Rivière. Manet’s biographer, Adolphe Tabarant, recalled Friday nights at the Café Guerbois as major social events, attended by Henri Fantin-Latour, Renoir, Degas, and occasionally Monet and Cézanne. On one such evening, Monet remembered Cézanne refusing to shake Manet’s hand, instead tipping his hat and saying, “I won’t offer you my hand, Monsieur Manet. I haven’t washed in eight days.”

Living the Legend: Cézanne and the Impressionist Imagination

Stories like this helped cement Cézanne’s image as a rugged, eccentric outsider—a persona first shaped by Zola and later amplified in literary and artistic circles. He became a living embodiment of Zola’s fictional archetypes: the defiant, unpolished artist challenging the norms of Parisian culture. His mythos—equal parts grit and genius—continues to resonate, not just through his paintings, but through the stories that surround them.

Retreat and Recalibration: Cézanne’s Final Break from the Impressionists

Following the relative success of the 1877 exhibition, Cézanne began to widen his social network, hoping to improve his prospects for selling work. Yet this expansion came with tension. Camille Pissarro, his longtime mentor and confidant, grew concerned that Cézanne might follow Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s path—submitting to the official Salon under the influence of Émile Zola and the Charpentiers. Such a move would effectively sever Cézanne’s ties with the Impressionist group, which had built its identity around independence from institutional validation.

Though Cézanne ultimately returned to Aix-en-Provence and did not participate in either the 1878 Salon or the postponed Fourth Impressionist Exhibition in 1879, he initially tried to reassure Pissarro. He asked Zola to lend The Black Clock, a moody, introspective still life painted in Zola’s home. The work, with its deep blacks and symbolic echoes of Manet’s portrait of Zola, signaled a return to Cézanne’s earlier themes—more literary, more psychological, and more studio-bound than the plein-air style favored by his Impressionist peers.

This gesture marked a subtle but significant shift. Rather than embracing the Impressionists’ collective momentum, Cézanne leaned into the solitary rigor of his own vision. He never exhibited with the group again.

His eventual acceptance into the official Salon came in 1882, with a somber portrait of his father reading L’Événement—the very newspaper where Zola had once championed the Impressionists. Behind the seated figure was a still life Cézanne had painted years earlier and gifted to Zola, creating a layered homage to their shared past. The painting was quiet, introspective, and deeply personal—far removed from the theatrical provocations of A Modern Olympia or the communal spirit of the Impressionist exhibitions.

Soon after, Cézanne left Paris.