Vincent Van Gogh

Blossoming Acacia Branches Initial Version, 1890

Blossoming Acacia Branches Version 2

Blossoming Acacia Branches Version 3

Blossoming Acacia Branches Version 4

Starry Night Over the Rhône, 1888 Initial Version

Starry Night Over The Rhone Version 2

Starry Night Over The Rhone Version 3

Starry Night Over The Rhone Version 4

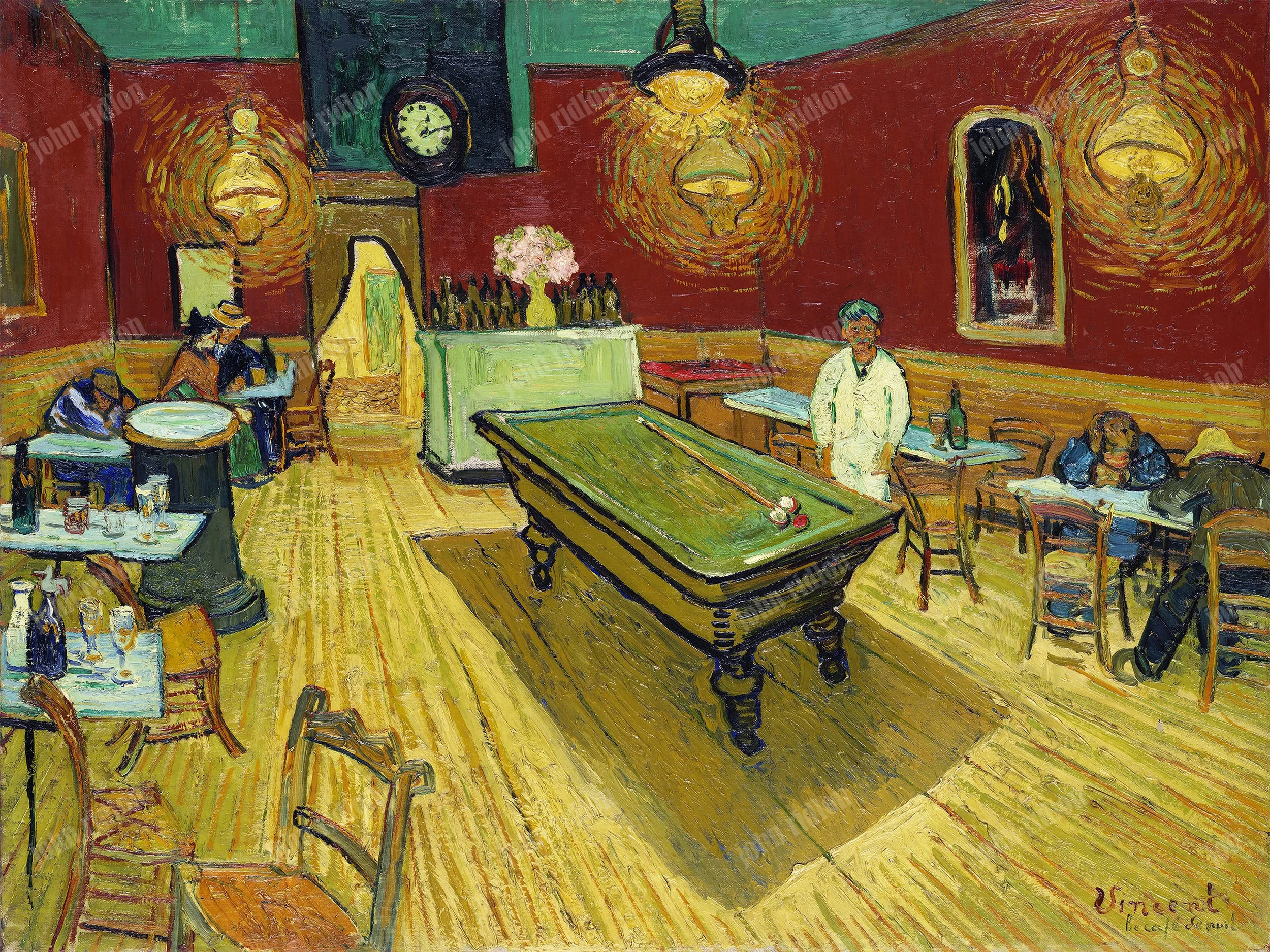

The Night Cafe 1888

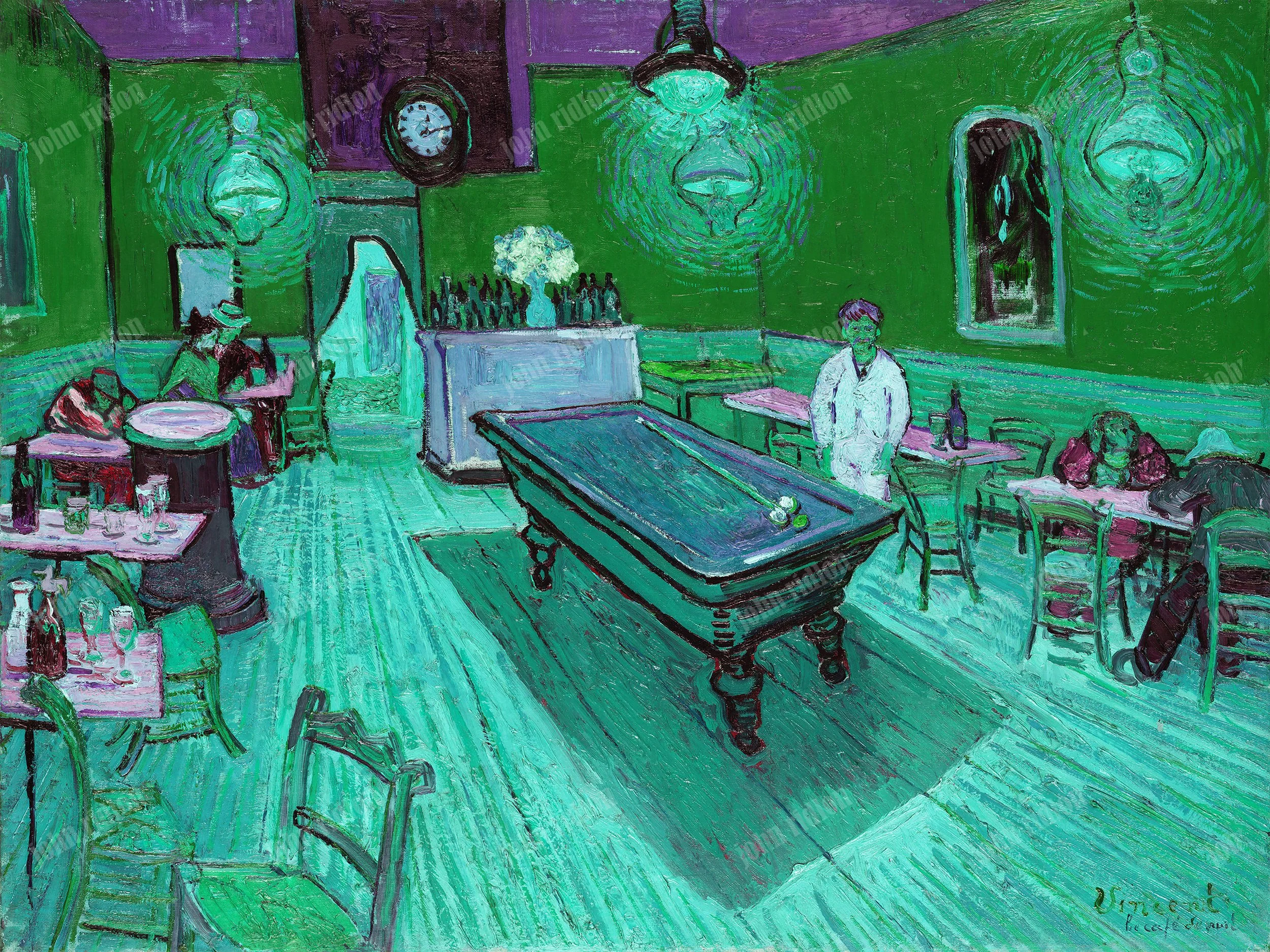

The Night Cafe 2 1888

The Night Cafe 1888 3

The Night Cafe 1888 4

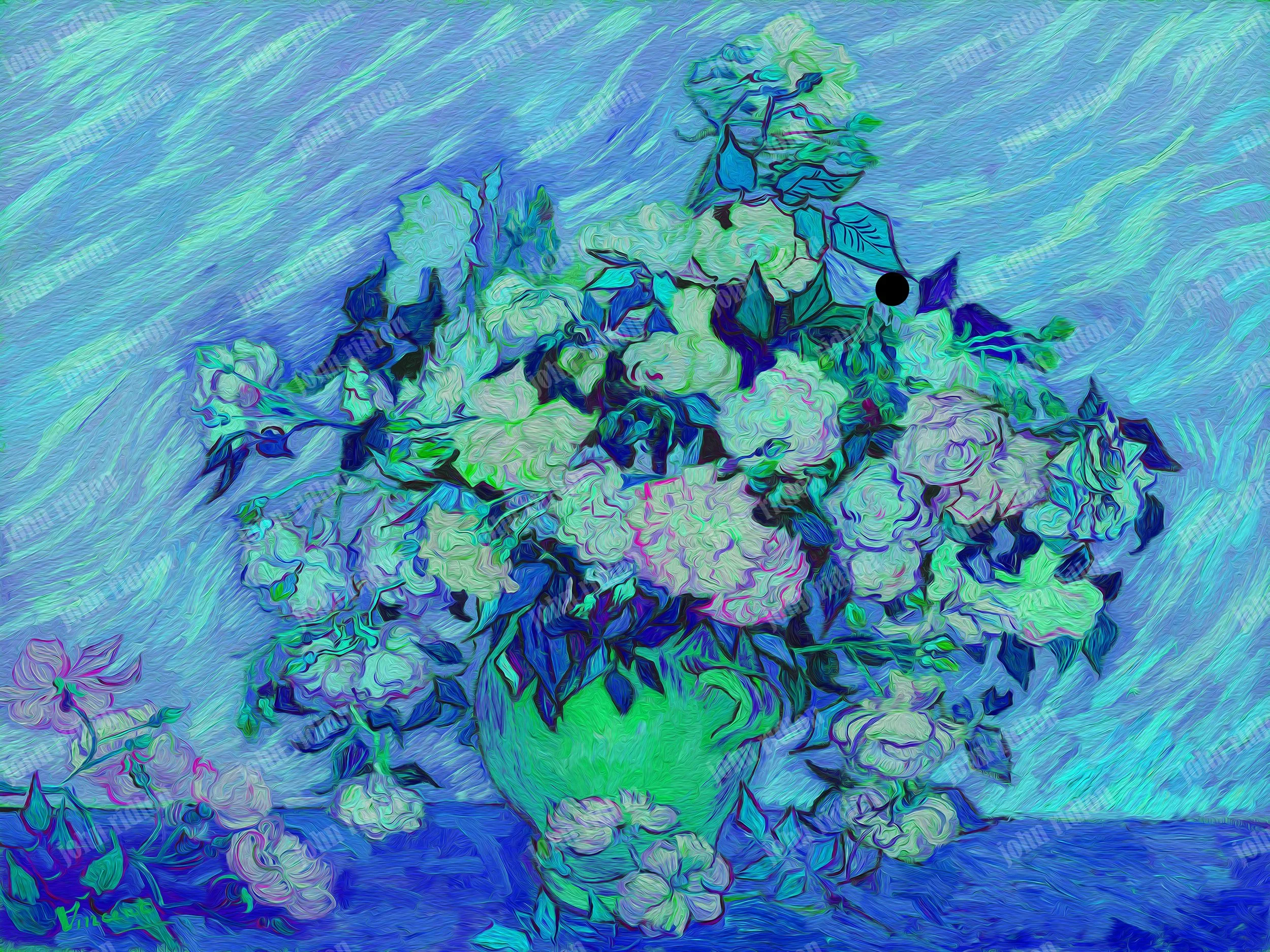

Roses Initial Version, 1890

Roses, 1890 Version 2

Roses Version 3

Roses Version 4

Farms near Auvers Initial Version, 1890

Farms near Auvers Version 2

Farms near Auvers Version 3

Farms near Auvers Version 4

Café Terrace at Night, 1888 Initial Version

Café Terrace at Night Version 2

Café Terrace at Night Version 3

Café Terrace at Night Version 4

Poppies, 1886 - Initial Version

Poppies - Version 2

Poppies - Version 3

Poppies - Version 4

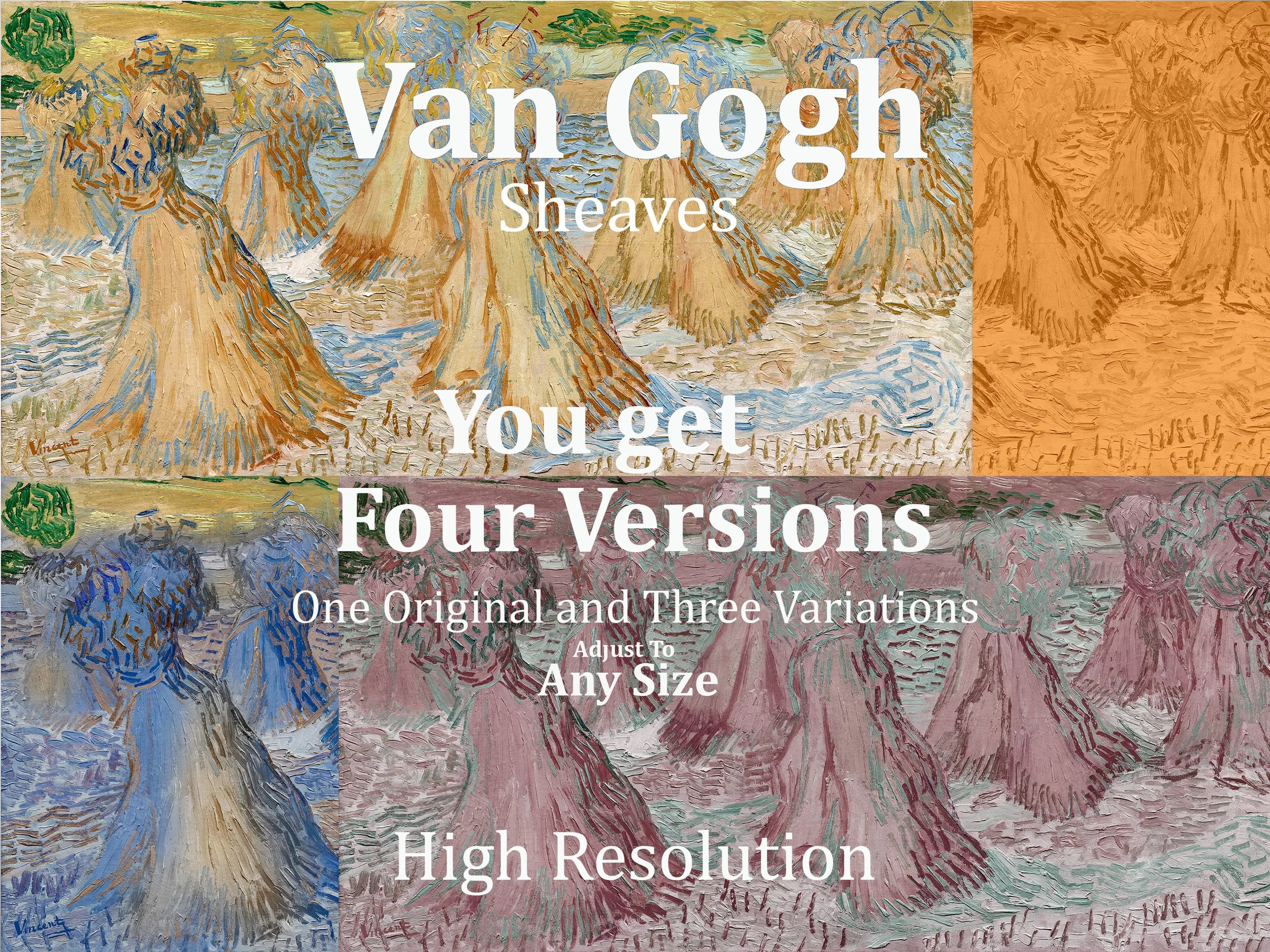

Sheaves, 1890 Initial Version

Sheaves Version 2

Sheaves Version 3

Les Arenes, 1888 Initial Version

Les Arenes, 1888 Version 2

Les Arenes Version 3

Les Arenes Version 4

The Siesta Initial, 1890 Version

The Siesta Version 2

The Siesta Version 3

The Siesta Version 4

The Starry Night, 1889 Initial Version

The Starry Night Version 2

The Starry Night Version 3

The Starry Night Version 4

Almond Blossom, 1890 Initial Version

Almond Blossom, 1890 Version 2

Almond Blossom Version 3

Almond Blossom Version 4

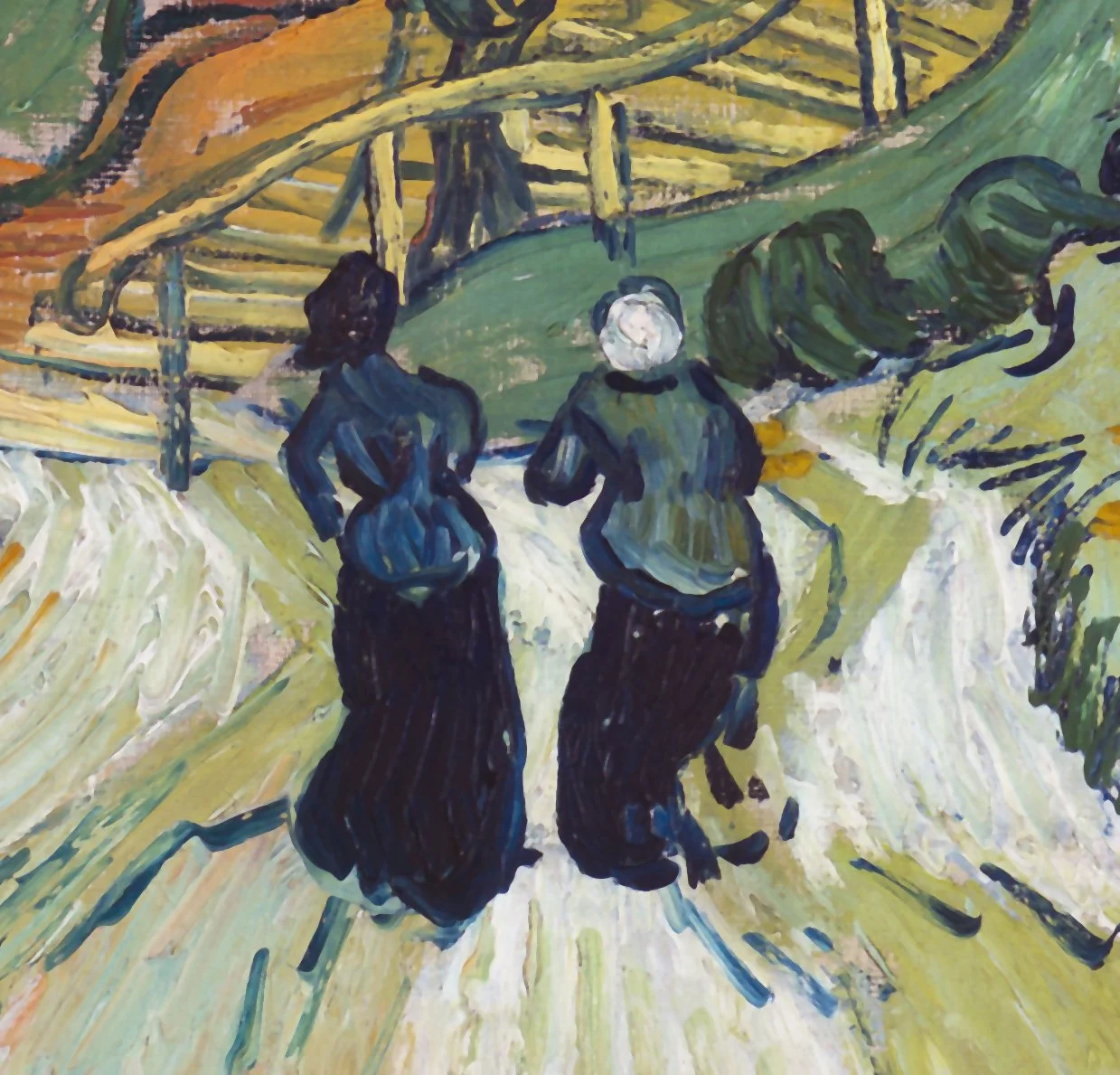

Stairway at Auvers, 1890 Initial Version

Stairway at Auvers Version 2

Stairway at Auvers Version 3

Stairway at Auvers Version 4

Street in Auvers, 1890 Initial Version

Street in Auvers Ve2ion 2

Street in Auvers Version 3

Street in Auvers Version 4

Irises, 1889 Initial Version

Irises Version 2

Lilacs - Version 3

Lilacs - Version lV

Irises, 1889 Version 1

Irises Version 3

Irises Version 4

Irises Version 3

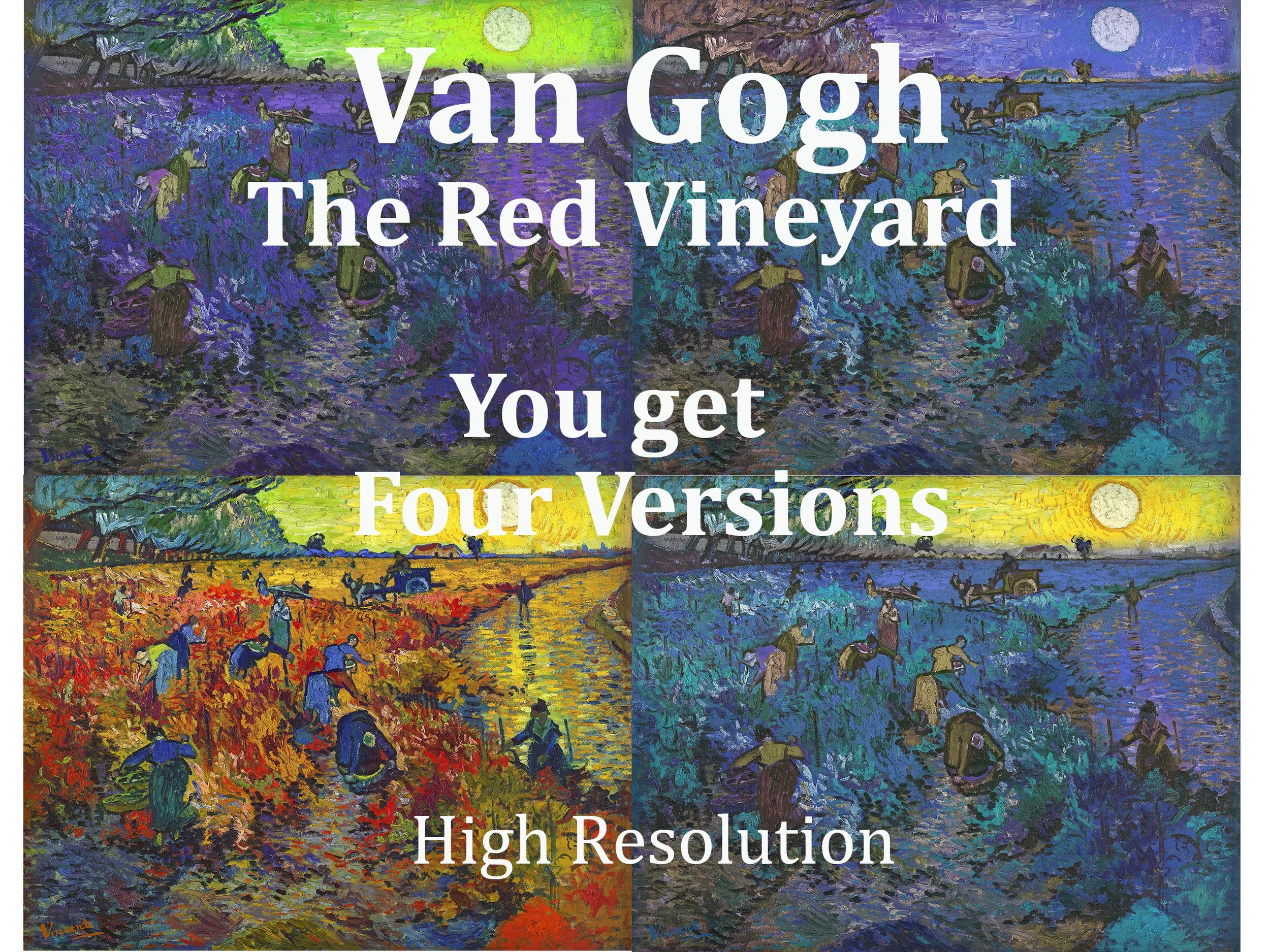

The Red, 1888 Vineyard Initial Version

The Red Vineyard Version 2

The Red Vineyard Version 3

The Red Vineyard Version 4

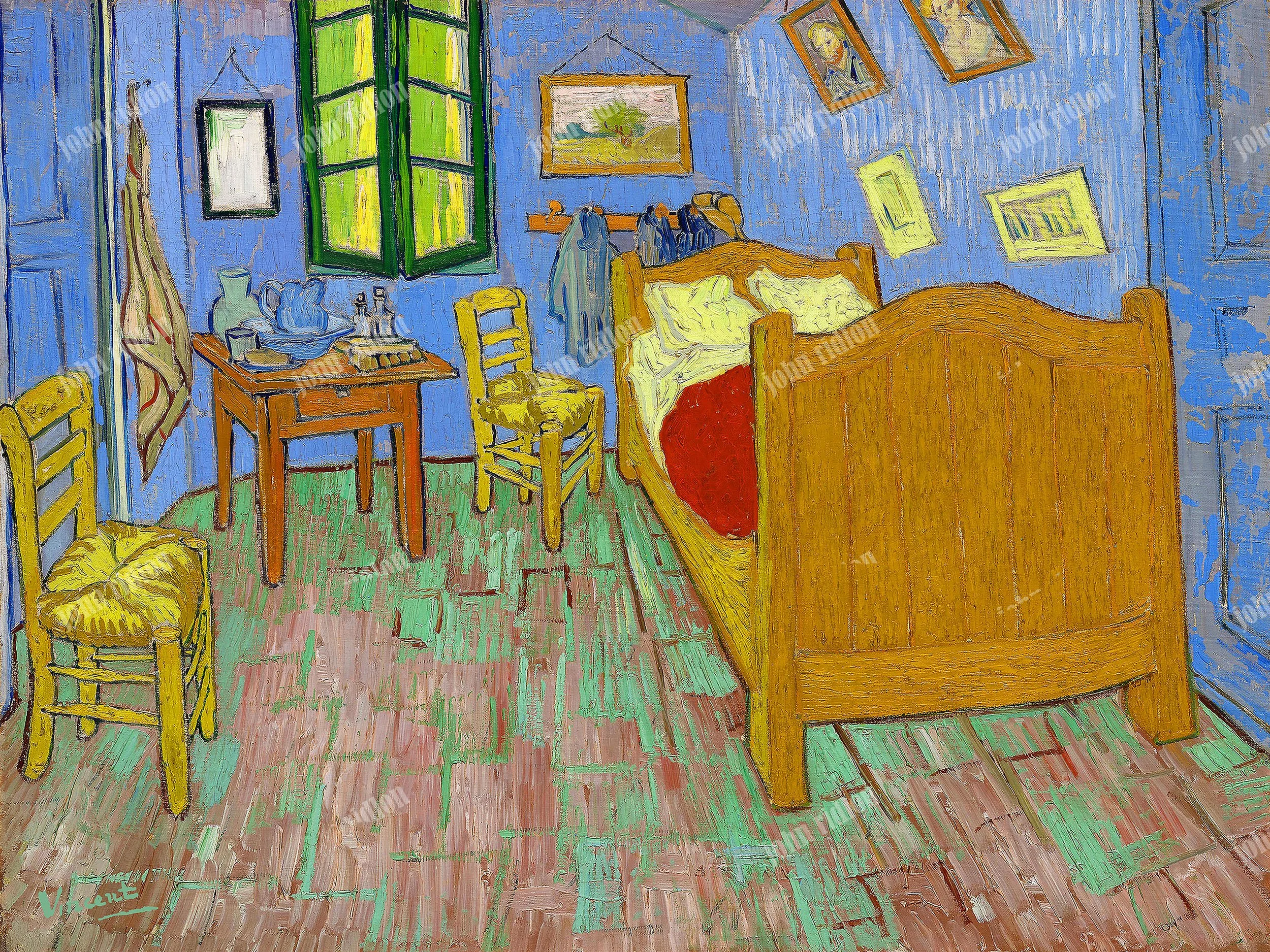

Bedroom in Arles, 1889 Initial Version

Bedroom in Arles Version 3

Bedroom in Arles Version 3

Bedroom in Arles Version 4

Fishing Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries, 1888 Initial Version

Fishing Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries Version 2

Fishing Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries Version 4

Fishing Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries Version 3

Sunflowers Roses And Other Flowers, 1888 Initial Version

Sunflowers Roses And Other Flowers Version 2

Sunflowers Roses And Other Flowers Version 3

Sunflowers Roses And Other Flowers Version 4

Sunflowers, 1887 Initial Version

Sunflowers Version 2

Sunflowers Version 3

Sunflowers Version 4

Imperial Fritillaries in a Copper Vase, 1887 Initial Version

Imperial Fritillaries in a Copper Vase Version 2

Imperial Fritillaries in a Copper Vase Version 3

Imperial Fritillaries in a Copper Vase Version 3

The Biography of Vincent Van Gogh

A Short Life, A Long Echo

Vincent’s story is often reduced to a tragic shorthand: the tortured genius, the lonely visionary. He died in 1890, just thirty-seven years old, from a gunshot wound whose circumstances remain uncertain. Recognition, which he had chased for a decade with little reward, arrived only after his death. Yet once the world caught up, it could not let go. His canvases became touchstones of modern art, and his letters one of the most revealing correspondences in art history.

But myth can obscure the man. To see Van Gogh clearly, one must return to the sources: to the letters filled with love and anguish, to the paintings alive with wheat fields, starlit skies, and human sorrow. He lived in a century of upheaval—industrialization, scientific discovery, shifting beliefs. Photography was changing vision; Japanese prints were reshaping composition. Van Gogh absorbed all of it. He did not imitate—he translated. He understood that sight is not merely optical; it is emotional. We do not only see with our eyes. We see with our hearts. That is why his work continues to speak—not as history, but as humanity itself.

The Artist and the Mirror

Van Gogh never separated life from art. He painted not only what he observed around him but what he carried within him. His canvases are autobiography in color; his letters, confessionals in ink. Where Paul Gauguin sought escape in distant lands, Vincent stayed close—to soil, sky, and the people who worked the land. He began within the tradition of Realism but soon broke beyond its confines. Inspired by the Impressionists, he transformed paint into a medium of revelation. For him, emotion itself became the subject. He did not chase perfection. He pursued truth.

Northern Roots: Holland and England

The beginnings were humble. Van Gogh’s early years unfolded among the flat landscapes and muted skies of the Netherlands. He sketched laborers, farmers, and weavers with an empathy that bordered on the spiritual. These were no idealized figures. They were men and women bent by toil, dignified in their endurance. His palette was dark, his lines rough, yet his honesty radiated through. These works were not images alone. They were acts of witness.

From childhood, Vincent carried a quiet intensity, more attuned to solitude than to play. He was remembered as peculiar, withdrawn, more old soul than boy. In his letters, he later described his youth as “gloomy, cold and sterile.” Yet in the countryside he found peace. He wandered the fields of Brabant, attuned to subtle changes in season and light. Nature was his first and constant companion. Even in his final illness, he recalled in precise detail the churchyard of his childhood, the garden, the acacia tree with its magpie’s nest.

This bond with the land shaped his worldview. Like his artistic hero Jean-François Millet, he saw the cycle of the seasons as a mirror of human life—birth, labor, death, renewal. The son of a pastor in a farming village, he would have known the verse from Genesis: “While the earth remaineth, seedtime and harvest, cold and heat, summer and winter, day and night shall not cease.” That rhythm echoed through his art forever after.

Schooling and Separation

Vincent’s formal education began locally but soon shifted. His parents worried about rough influences from village boys, so he was sent first to a governess, then to Jan Provily’s boarding school in Zevenbergen. The separation marked him deeply. In a later letter, he remembered standing on the school steps, watching his parents’ carriage disappear down a rain-soaked road lined with bare trees and mirrored puddles. The image, both visual and emotional, reveals his gift: to bind memory with sensation so that it lingers like a painting in words.

After two years, he moved to a state-run boarding school in Tilburg. There he excelled at languages—French, English, German—and began formal drawing lessons. But his schooling ended abruptly, just before his fifteenth birthday. Financial hardship likely played a role. His formal education never resumed.

First Steps into Art

After leaving school, Vincent spent a quiet year at home, uncertain of his path. His uncle Cent, a respected art dealer, offered a direction. In 1869, Vincent entered Goupil & Co., an international art firm with offices in The Hague. The company specialized in engravings and reproductions of Salon and Barbizon painters, including Millet and Rousseau, whose reverence for rural life and nature resonated with Vincent. Their work revealed to him that art could dignify the laboring classes and sanctify the land itself.

At Goupil, Vincent proved capable, well-liked, even imaginative—making booklets of animal drawings for the manager’s daughter. His letters to Theo, who soon joined the firm himself, became lifelines, weaving brotherly love with aesthetic reflection. “Always your loving brother, Vincent,” he signed them, a refrain he kept to the end.

By 1873, his diligence was rewarded with promotion to London.

London: Wonder and Wound

In London, Van Gogh arrived with hope and a top hat, earning a respectable salary and a reputation as a rising dealer. The city dazzled him with its parks, galleries, and gaslit streets. At the Royal Academy he admired Millais and Constable; in literature he immersed himself in Keats, Dickens, and the English Social Realists. Their depictions of poverty and endurance resonated with his own growing moral urgency.

But London was also a place of shadows. He collected engravings from The Graphic and Illustrated London News—images of hardship etched with empathy. Gustave Doré’s London: A Pilgrimage haunted him with its crowded alleys and stark contrasts. For Vincent, art and compassion were inseparable. “An artist needn’t be a clergyman,” he wrote, “but he must have a warm heart for his fellow men.”

Yet amid this cultural awakening came heartbreak. Lodging in Brixton with the Loyer family, Vincent fell in love with Eugenie, his landlady’s daughter. When she rejected his proposal, his heart shattered. His persistence turned painful, and eventually he was forced to leave. The experience marked the beginning of years of emotional turmoil. “Poor boy,” his mother wrote to Theo, “he does not take life easily.”

The rejection altered his spirit. His passion for selling art waned; religion and inner reflection consumed him. Ernest Renan’s words—“Religion is not a philosophy, but a history; not an abstract doctrine, but a life”—became a guiding flame. He began searching, not for career success, but for meaning.

Paris and the Turn to Faith

Transferred to Goupil’s Paris office in 1874, Vincent found himself unsettled, depressed, and spiritually restless. While he admired Rembrandt and Millet, his fervor grew increasingly religious. He lived austerely, denying himself comforts, and filled his letters with biblical passages. He believed sacrifice might lead to truth. “Take off your shoes,” he wrote after viewing Millet’s drawings, “for the place where you are standing is Holy Ground.”

But zeal unnerved those around him. By 1875 his behavior became erratic, and after nearly seven years with Goupil, he was pressured to resign. His professional world collapsed. What remained was faith.

Teaching, Preaching, and Seeking

In 1876, he taught briefly in Ramsgate and then London, taking modest posts with little pay. Collecting school fees in the East End, he saw the poverty Dickens had described and felt called to witness it. He sketched, read scripture, and found solace in preaching. When invited to the pulpit in Turnham Green, he chose Psalm 119: “I am a stranger on the earth; hide not Thy commandments from me.” The words captured his own sense of exile.

Back in the Netherlands, he pursued theology, but academic hurdles defeated him. His devotion deepened into obsession. He fasted, deprived himself of sleep, punished himself with cold. Colleagues worried for his health. The Church eventually dismissed him as too zealous.

The Borinage: Faith in Action

In 1879, in Belgium’s coal-mining Borinage, Van Gogh tried to live as Christ among the poor. He gave away his possessions, slept on straw, and smeared coal dust on his face to share the miners’ suffering. He tended to the sick and preached redemption through endurance. But his radical empathy alarmed the Church, and after six months he was dismissed for “excess of zeal.” “They turned me out like a dog,” he said, “because I tried to relieve the misery of the wretched.”

Broken yet transformed, Vincent began to draw. In misery, he found clarity. “I shall set to work again with my pencil,” he wrote in 1880, “and from that moment everything has changed for me.”

At twenty-seven, he chose his vocation—not to preach in words, but in paint.

A New Evangel: Art

In Brussels, he studied anatomy, perspective, and form. He devoured Rubens, whose dynamism showed him how painting could move beyond description to revelation. Theo, now thriving in the art trade, sent him money—support that sustained Vincent for the rest of his life. Their relationship, tender yet tense, grew ever more central.

He befriended Anthon van Rappard, a young artist, and produced early drawings of miners and laborers, infused with empathy and raw force. When Rappard left, Vincent returned home, seeking in familiar landscapes the beginnings of a new voice.

His suffering had not ended. But his art had begun.

s

Van Gogh’s reverence for the Dutch masters deepened. He admired Frans Hals for his bold, spontaneous brushwork and Rembrandt for his spiritual gravity and mastery of light and shadow. These artists, he felt, painted not just faces but souls. Their work challenged him to create a modern equivalent—art that could speak to the human condition with honesty and depth. Portraiture, for Van Gogh, became a kind of history painting for his own time—a way to document not events, but emotions.

Becoming “Vincent”

By now, Van Gogh had shed his former identity. His faith in the institutional Church had collapsed, and his commitment to art had become absolute. To mark this transformation, he began signing his work simply “Vincent.” It was a symbolic break from the Van Gogh family name—a gesture of independence, and perhaps a nod to Rembrandt, who also signed his work with only his first name.

Etten: A Return and a Reckoning

Back in Etten, Van Gogh’s health improved. He painted outdoors, reconnecting with the land and the people. He embraced the idea that truth—however harsh—was rooted in rural life. “When I say I am a painter of peasant life, that is a fact,” he wrote. His evenings spent with miners, weavers, and peat cutters had shaped his vision. He found kinship in the work of Millet, Breton, Lhermitte, and Mauve, and in the Dutch tradition of Rembrandt and Hals. Yet his spiritual independence remained fierce. “Their whole system of religion is horrible,” he wrote to Theo, rejecting the moral rigidity of his upbringing.

Another Wound

During the summer of 1881, Van Gogh fell in love again—this time with his widowed cousin, Kee Vos-Stricker. She was visiting Etten with her young son. Vincent declared his feelings, but Kee rejected him outright. Undeterred, he pursued her, even traveling to Amsterdam to plead his case. Her father refused to let him see her.

In a dramatic moment, Vincent placed his hand over a flame and said, “Let me see her for as long as I can keep my hand in the flame.” The lamp was extinguished. He was told, “You shall not see her.” His mother sided with Kee. From that moment, Vincent considered her a stranger. Kee vanished from his letters, and the emotional rupture was permanent.

Painting in Earnest

Unable to remain at home, Van Gogh moved to The Hague. He lived in poverty on the industrial outskirts of the city, but he was free—and determined. He began painting seriously, visiting Anton Mauve for guidance and continuing to refine his technique. For the next 18 months, he worked obsessively, laying the foundation for the expressive style that would soon emerge.

Père Millet: A Prophet in Paint

To Van Gogh, Jean-François Millet was more than a painter—he was a spiritual guide. Revered as the “peasant-painter,” Millet embodied the values Van Gogh longed to inherit: humility, reverence for labor, and a deep connection to the land. “Millet is father Millet,” Van Gogh wrote, “counsellor and mentor in everything to the younger painters.” His religious fervor, once channeled through sermons, now found expression in brushstrokes. Art had become his gospel.

The Hague: A Style Begins to Emerge

In The Hague, Van Gogh began to paint in earnest. With guidance from his cousin Anton Mauve and the help of instructional manuals, he developed a style that was raw, awkward, and unmistakably his own. He worked obsessively with pen and ink, chalk, and litho crayon—tools that echoed the engravings he had collected from English periodicals.

His empathy for the poor and working class fueled his vision, and his powers of observation gave his drawings a stark immediacy. He struggled with perspective, a challenge for any artist depicting the flat Dutch landscape. To solve this, he built a simple drawing frame inspired by Albrecht Dürer and the old Dutch masters. It allowed him to break down scenes into geometric patterns, turning what once felt like “witchcraft” into a tool of expressive clarity. Perspective, once elusive, became part of his visual vocabulary.

Drawing the City: A New Kind of Realism

Commissioned by his Uncle Cor to document the changing face of The Hague, Van Gogh produced a series of pen and ink drawings that rejected picturesque convention. He avoided tourist landmarks, focusing instead on roadworks, poor neighborhoods, and the people who lived there. “Full reality,” he called it.

These works, rooted in the visual language of magazine illustration, marked the beginning of Van Gogh’s mature style. His character studies were powerful and unsentimental—figures rendered with empathy but without romanticism. The strong, chiseled lines and dramatic tonal contrasts gave his subjects a dignity that transcended their circumstances. These were not portraits of individuals—they were archetypes of human endurance.

Studying the Masters

As Van Gogh’s artistic journey deepened, so too did his reverence for the great Dutch masters. He looked to Frans Hals with admiration for the painter’s astonishing bravura—brushstrokes that seemed to dance with improvisational energy, capturing the vitality of sitters with an immediacy that defied convention. In Rembrandt, he discovered something even more profound: a spiritual gravity that transcended mere likeness. Light and shadow in Rembrandt’s canvases were not technical devices alone, but metaphors for the soul’s struggle, the drama of human existence.

For Vincent, these painters did more than depict appearances—they revealed inner truths. They offered a model of painting as revelation, as testimony. To follow in their footsteps was not simply to imitate but to translate their genius into the modern age. His challenge was to create a contemporary equivalent: art capable of speaking honestly to the human condition, art that conveyed not only what people looked like but what they felt and suffered.

In this spirit, portraiture emerged as central to his mission. For Van Gogh, the face became a battlefield of emotions, a map of human endurance. He conceived of portraiture as a modern history painting—not a record of public events, but a chronicle of private struggles and inner states of being.

Becoming “Vincent”

This period also marked the rebirth of Van Gogh’s identity. The collapse of his religious vocation had left him estranged from the institutional Church, and the role of preacher was now fully eclipsed by the vocation of painter. His commitment to art hardened into something absolute, even sacred.

To signal this transformation, he began signing his canvases simply with his first name: “Vincent.” The gesture was at once intimate and radical. It stripped away the weight of family heritage and societal expectation, asserting instead a singular, uncompromising identity. In doing so, he aligned himself with the tradition of Rembrandt—another Dutch master who had used his first name as an emblem of personal authenticity. For Vincent, the signature was more than ink on canvas; it was a declaration of artistic faith.

Etten: A Return and a Reckoning

When Van Gogh returned to Etten in 1881, he found his health improving, and with it, his connection to the rhythms of rural life. He immersed himself in the fields and gardens, painting outdoors with an intensity that bordered on the devotional. To him, the truth of art was rooted in the soil and in the labor of ordinary people. “When I say I am a painter of peasant life, that is a fact,” he wrote, reaffirming his sense of calling.

These convictions had been shaped by earlier experiences—his evenings spent with miners in the Borinage, his encounters with weavers and peat cutters, his studies of peasants bent over their work. In the lives of the poor, he recognized not only hardship but a universal dignity. He aligned himself with a lineage of artists who had elevated humble subjects into vehicles of spiritual meaning: Jean-François Millet, Jules Breton, Léon Lhermitte, and his cousin Anton Mauve. To these he added the weight of Dutch tradition—Rembrandt’s humanity, Hals’s vigor—yet he forged his own path with a spirit of defiance.

Even as his art rooted itself in human endurance, Van Gogh’s relationship with organized religion grew more embittered. The rigid moralism of his upbringing felt increasingly suffocating. “Their whole system of religion is horrible,” he confided to Theo, distancing himself not from faith itself but from the institutions that claimed to embody it. His spirituality, now independent and deeply personal, would flow into his brushstrokes.

Another Wound

Yet life in Etten was not without turbulence. In the summer of 1881, Vincent fell deeply in love with his widowed cousin, Kee Vos-Stricker, who was visiting with her young son. He pursued her with passionate intensity, declaring his devotion despite her clear rejection. When her father barred him from seeing her, Vincent responded with characteristic drama: he pressed his hand into a flame, vowing to keep it there until he was allowed to see her. The lamp was swiftly extinguished, and the verdict pronounced—“You shall not see her.”

The episode severed him from his cousin and cast a shadow over his family relations. His mother sided with Kee, and what had once been a fragile bond between Vincent and his relatives fractured further. Kee disappeared from his life and from his correspondence, leaving behind an emotional wound that would linger. For Vincent, it was yet another experience of unrequited love, another reminder of his outsider status.

Painting in Earnest

Unable to remain in the suffocating atmosphere of home, Van Gogh relocated to The Hague. Though he lived in poverty on its industrial margins, he was unshackled—and free to work with obsessive dedication. There, under the mentorship of Anton Mauve, he began painting seriously, committing himself to a life of relentless practice.

For the next eighteen months, Van Gogh labored tirelessly, building the foundation of his style. His art, raw and unrefined, pulsed with urgency. He filled sheets with pen and ink studies, scrawled figures in chalk and crayon, and experimented with lithography. His eye was drawn to the engravings in English illustrated periodicals—images of miners, laborers, and the poor—which shaped his vocabulary of stark lines and dramatic contrasts. These works were not decorative but confrontational, demanding recognition of human hardship.

Struggling with perspective, he devised a simple wooden drawing frame—an echo of Albrecht Dürer’s devices and of old Dutch practice—that allowed him to dissect scenes into geometric grids. What had once seemed like “witchcraft” became a practical tool, enabling him to capture space with greater clarity. Technique, for Van Gogh, was never an end in itself, but a means to channel truth.

Van Gogh Quiz

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.