Oscar-Claude Monet

Woman with a Parasol, 1875 - Initial Version

Woman with a Parasol - Version 2

Woman with a Parasol - 3

Woman with a Parasol - 4

The Luncheon 1868

Hauling a Boat Ashore, Honfleur 1864

In the Meadow 1876

Flowers and Fruit 1869

Le Rue de la Bavole at Honfleur 1864

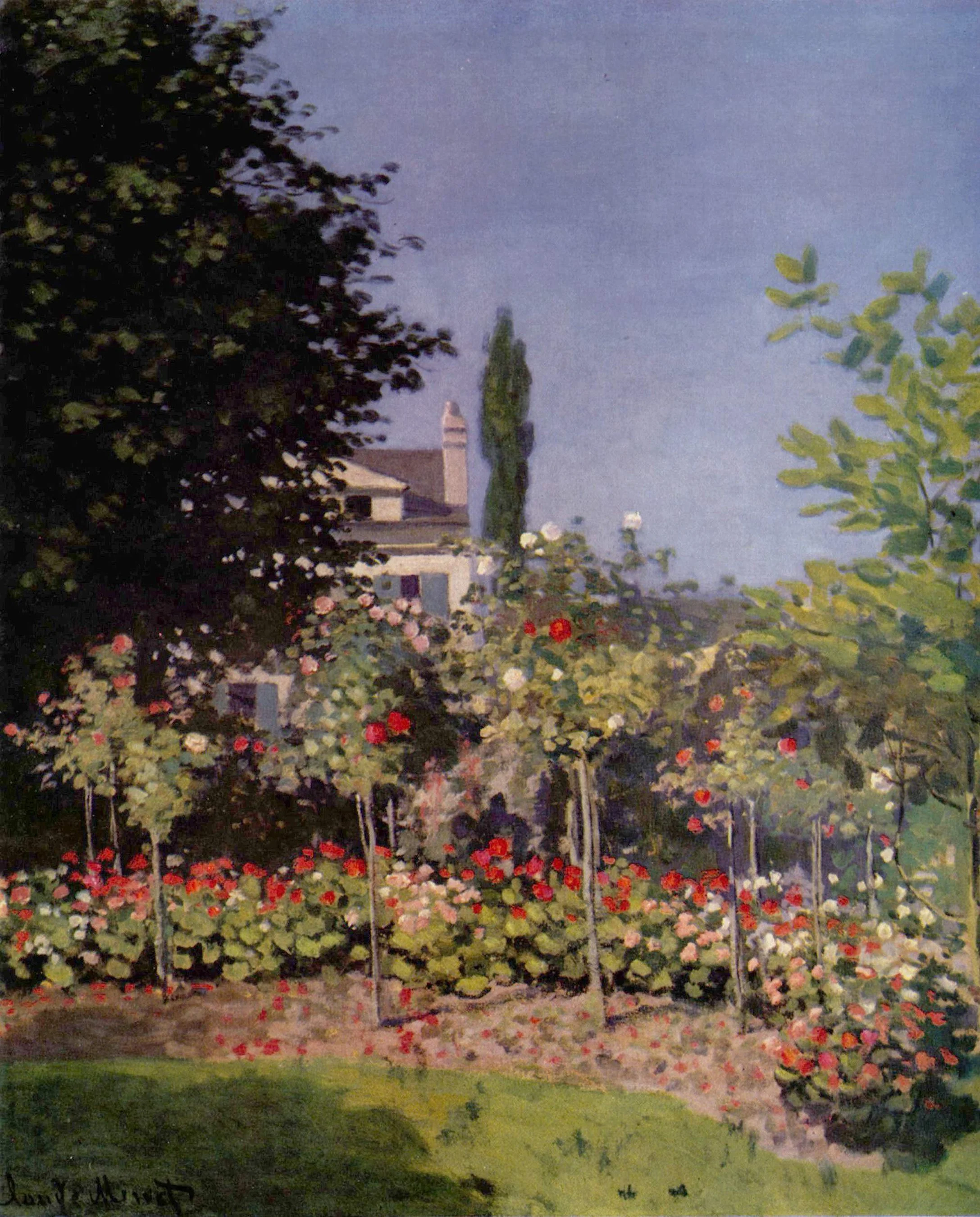

Garden in Flower 1866

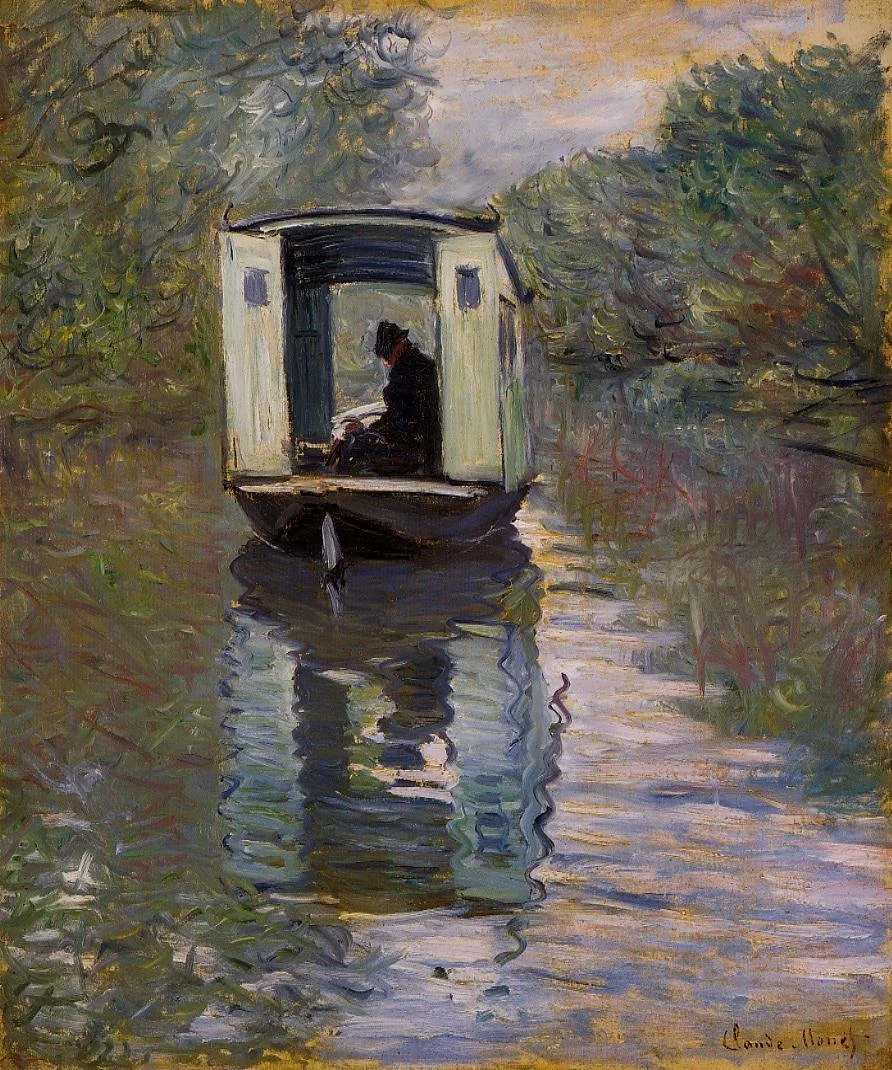

The Studio Boat, 1864

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe - left panel Unfinished Painting, 1866

Boulevard des Capucines 1873

Embankment in Le Havre 1874

Fishing Boats Leaving the Port of Le Havre 1874

Camille Monet in Japanese Costume 1875

Water Lilies (Agapanthus) - Initial Version, 1920

Water Lilies (Agapanthus) - Version 2

Water Lilies (Agapanthus) - Version 3

Water Lilies (Agapanthus) - Version 4

Poppies in a China Vase, 1883

The Artists Garden in Argenteuil, 1873 - Intial Version

The Artists Garden in Argenteuil-Version 4

The Artists Garden in Argenteuil-Version 3

The Artists Garden in Argenteuil-Version 2

The Bridge at Argenteuil-Version 2

The Bridge at Argenteuil, 1874 - Intial Version

The Bridge at Argenteuil-Version 3

The Bridge at Argenteuil-Version 4

Artists Garden at Vetheuil, 1876 - 1

Artists Garden at Vetheuil - 2

Artists Garden at Vetheuil - 3

Artists Garden at Vetheuil - 4

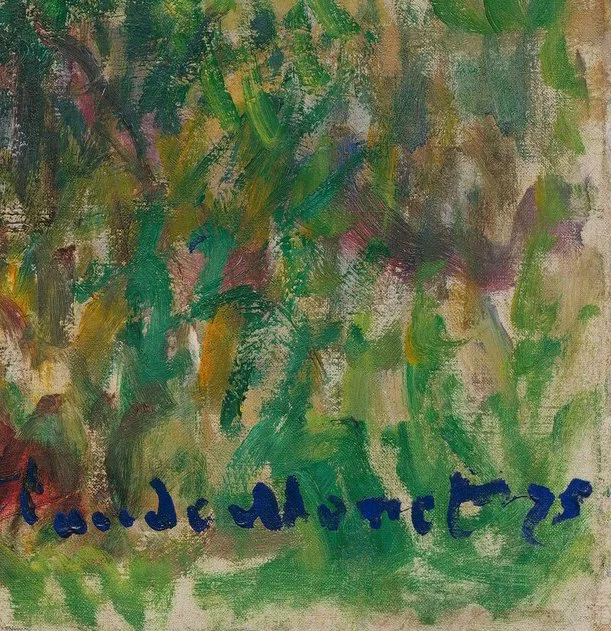

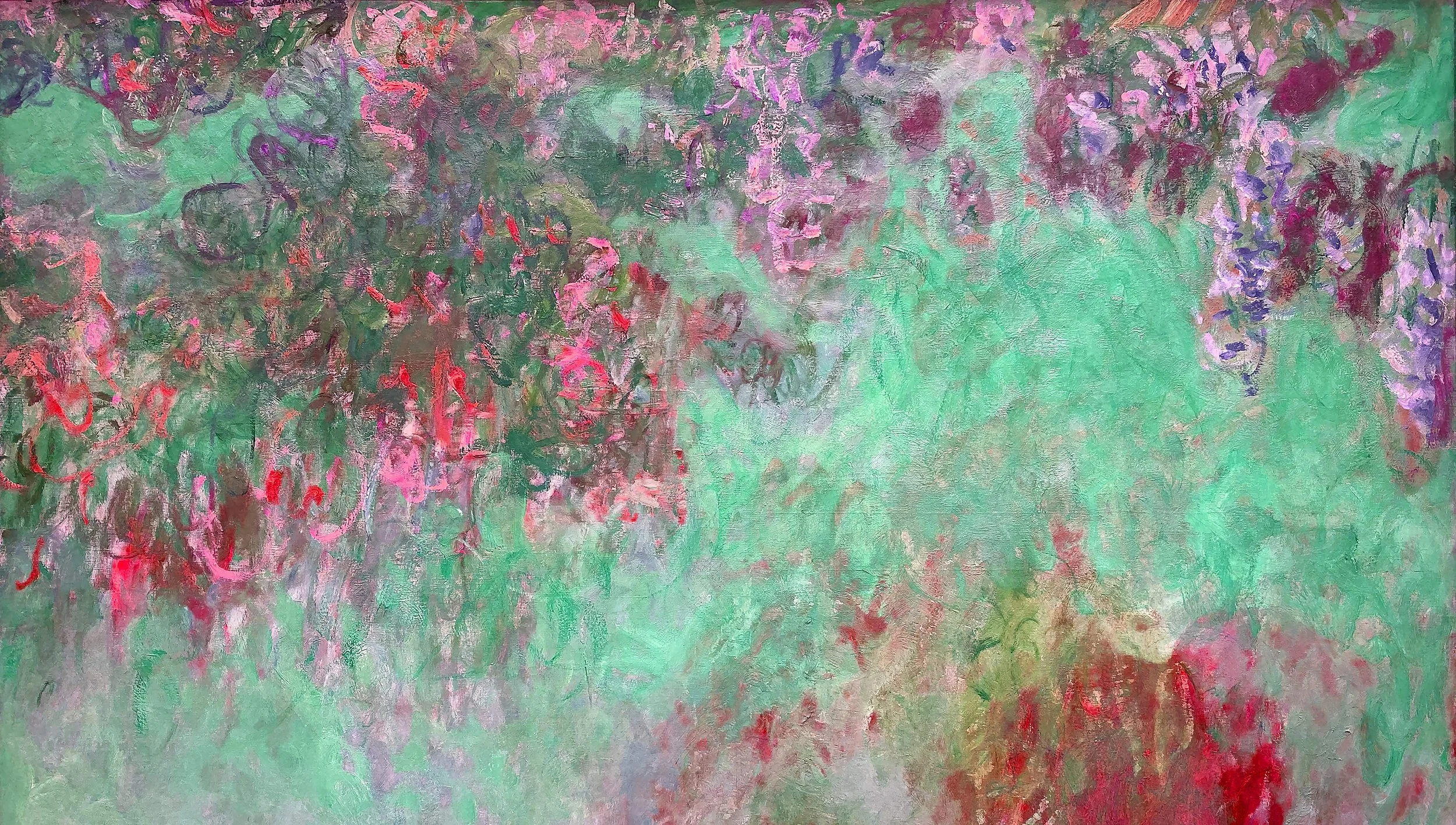

The Rose Garden, 1923 - Initial Version

The Rose Garden - 2

The Rose Garden - 3

The Rose Garden - 4

The Bench 1873

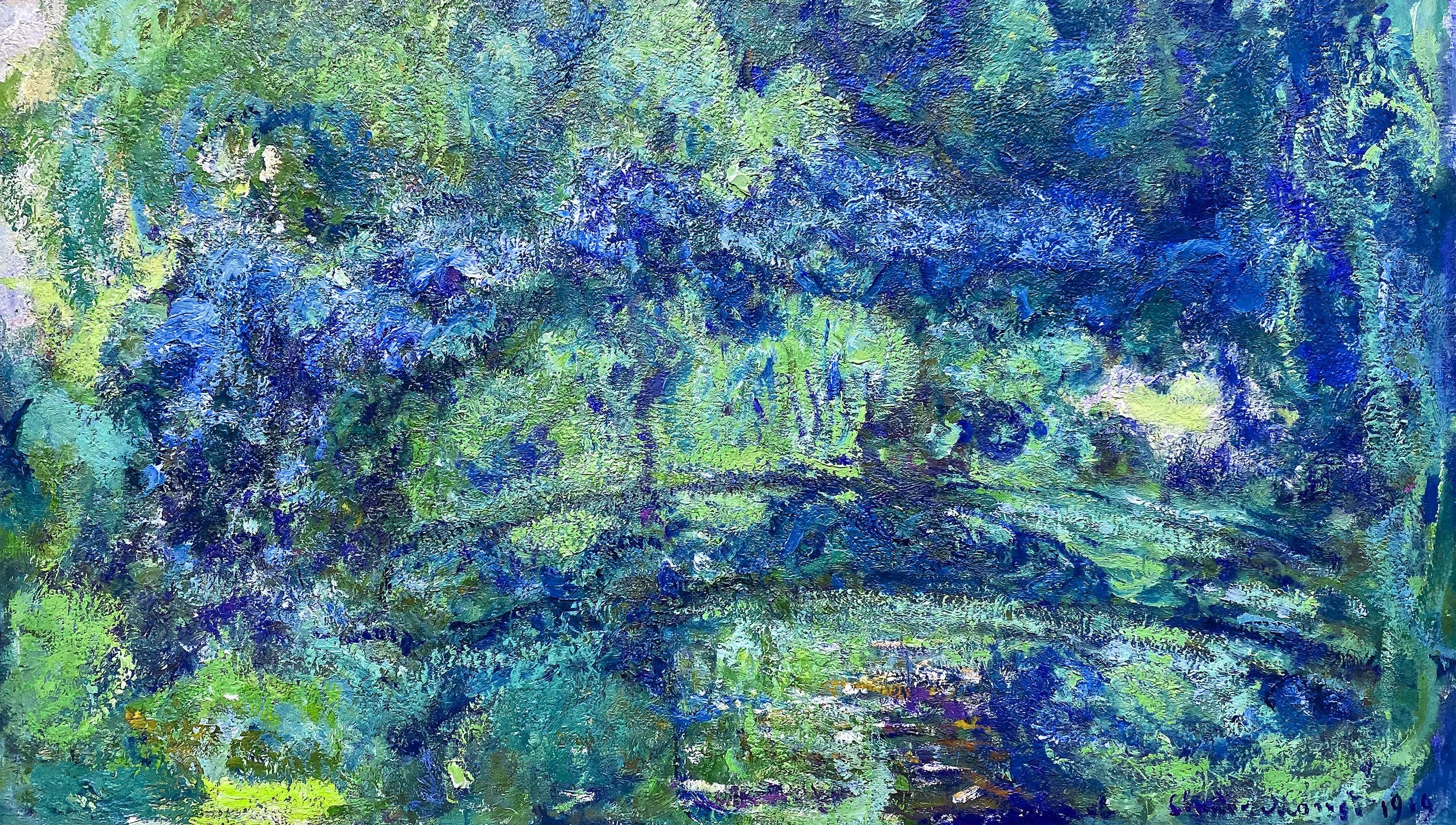

The Footbridge over the Water-lily pond 1919 - Initial Version

The Footbridge over the Water-lily pond 1919 - Version 2

The Footbridge over the Water-lily pond 1919 - Version 3

The Footbridge over the Water-lily pond 1919 - Version 4

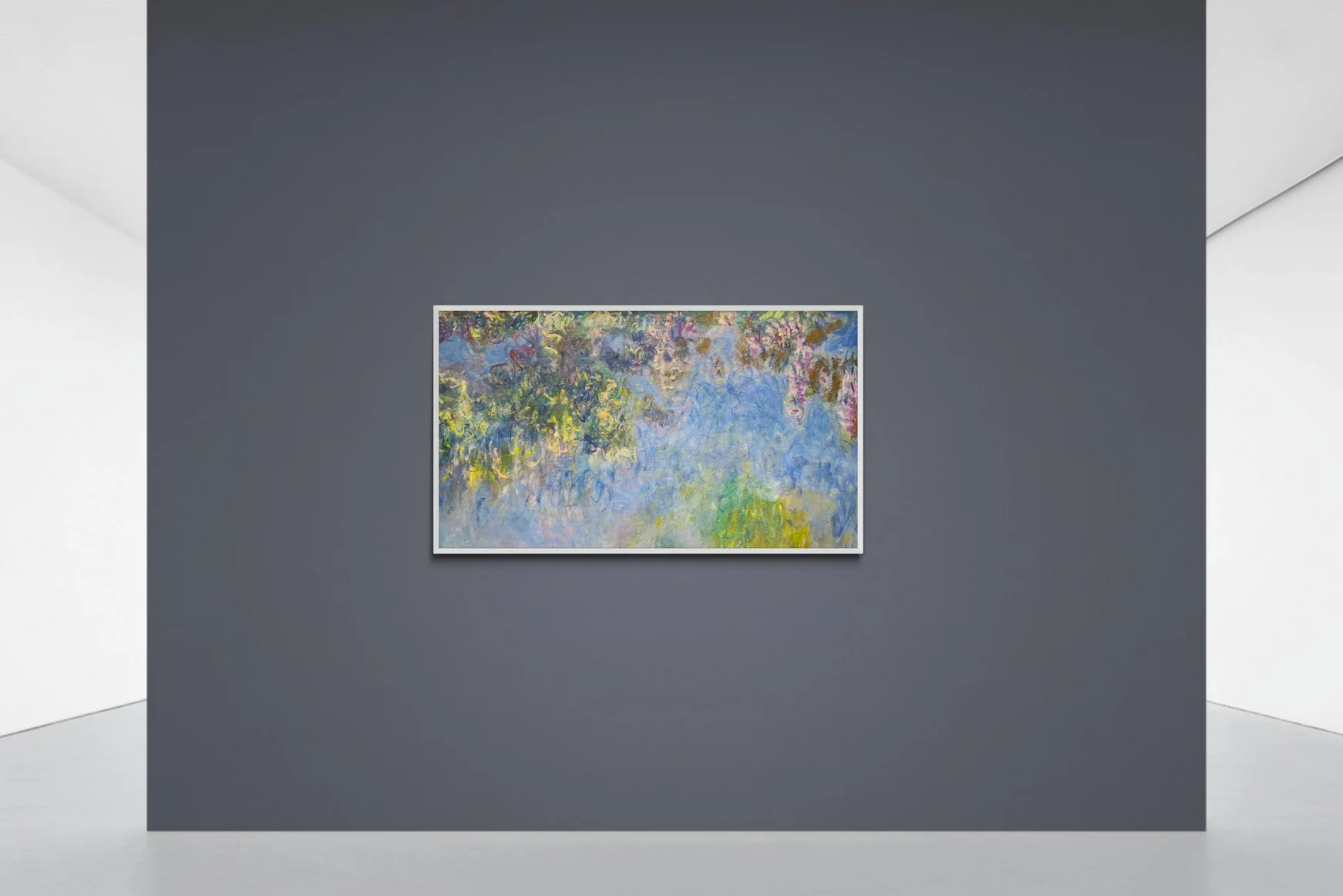

Wisteria, 1920-25 - Initial Version

Wisteria, 1920-25 - Version 2

Wisteria, 1920-25 - Version 3

Wisteria, 1920-25 - Version 4

Springtime Apple Blossoms in the Wind, 1925 - Initial Version

Springtime Apple Blossoms in the Wind - Version 2

Springtime Apple Blossoms in the Wind - Version 3

Springtime Apple Blossoms in the Wind - Version 4

The Water Lily Pond, 1918 - Initial Version

The Water Lily Pond, 1918 - Version 2

The Water Lily Pond, 1918 - Version 3

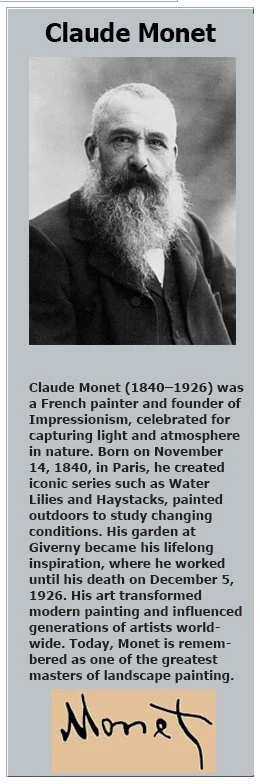

Monet Biography

Claude Monet: The Making of an Impressionist

Claude Monet’s name is forever entwined with the movement he helped define—Impressionism. It was his own painting, Impression, Sunrise (1872), that gave the movement its name. More than any of his peers, Monet remained unwavering in his quest to capture fleeting light, atmospheric subtlety, and the essence of a moment. He was prolific, exacting, and often restless—rarely content with the light, the time, the earnings, or the acclaim.

To know Monet in his early years was to shoulder the weight of emotional and financial strain. His friend Frédéric Bazille, generous and loyal, experienced this firsthand. The young artist who once traded caricatures and painted on scraps would, in time, become a celebrated figure—commanding thousands for a single canvas of a grain stack and deftly managing art dealers to keep his prices high.

Normandy Beginnings

Claude Oscar Monet was born in Paris on November 14, 1840, the younger of two sons. At age five, his father Adolphe relocated the family to Le Havre, a thriving port city on the Normandy coast, where they joined the Lecadres—relatives who ran a successful wholesale and ship chandlery business.

From an early age, Monet displayed a natural gift for drawing. At the Collège du Havre, he studied under Charles Ochard, a teacher trained by Jacques-Louis David, the famed Neo-Classicist and court painter to Napoleon I. Yet Monet was never a conventional student. “I more or less lived the life of a vagabond,” he recalled in 1900. “By nature I was undisciplined; never, even as a child, would I submit to rules.”

School felt stifling. The sea, the sunlight, and the open air beckoned more than any classroom. By fifteen, Monet had gained local fame for his irreverent caricatures of teachers—boldly drawn and laced with biting humor. Beneath the mischief, however, was a serious artistic drive, nurtured by his aunt Mme Lecadre, an amateur painter who took a keen interest in his development, especially after the death of his mother in 1857.

Monet’s growing devotion to art strained his relationship with his father, who urged him to pursue a stable career. Mme Lecadre, with support from painter Armand Gautier, persuaded Adolphe to allow Claude to follow his passion. Monet skipped the baccalaureate exam and left school without formal qualifications—armed only with a fierce belief in his own path.

A Revelation in the Landscape

Though talented, Monet lacked formal training and resisted academic instruction. A turning point came when Gravier, a local frame-maker who displayed Monet’s drawings in his shop, introduced him to Eugène Boudin, a respected landscape painter.

Monet was initially unimpressed. He found Boudin’s work crude and disliked the naturalistic style, having been raised on stylized, fantastical compositions. But Boudin invited him on a plein air painting excursion—and the experience changed everything.

“I understood,” Monet later said. “I had seen what painting could be, simply by the example of this painter working with such independence at the art he loved. My destiny as a painter was decided.”

From that moment, Monet embraced the outdoors as his studio. The shifting light, drifting clouds, and shimmering water became his subjects, his obsession, and ultimately his legacy.

Paris Beckns

Monet applied for a municipal grant to study art in Paris but was rejected. Undeterred, he scraped together savings—mostly from caricature commissions—and headed to Paris in the spring of 1859. Armed with letters of introduction from Boudin, he met several artists, including Troyon and Gautier. Troyon recognized his promise and recommended he study at the atelier of Thomas Couture, a respected teacher whose students included Édouard Manet.

Monet declined. He disliked the rigidity of academic instruction and returned to Le Havre. Yet Paris continued to call. By the winter of 1860, he was back—this time drawing live models at the free Académie Suisse. There, he met Camille Pissarro, a fellow artist who would become a lifelong friend and collaborator.

Their meeting marked the beginning of a new chapter—not only for Monet, but for the birth of a movement that would reshape the course of art history.

Defiance and Discovery: Monet’s Military Interlude

In 1861, Claude Monet’s name was drawn for military service—a seven-year obligation dreaded by many young men. Families with financial means could pay to exempt their sons, and Adolphe Monet offered to do so—on one condition: Claude must abandon his artistic ambitions and join the family business. Monet, true to his nature, refused. With characteristic resolve, he enlisted in the Chasseurs d’Afrique, a cavalry regiment stationed in Algeria.

The North African landscape left a lasting imprint on his artistic sensibility. The clarity of light, the vastness of space, and the intensity of color would echo throughout his later work. Yet his time in Algeria was brief. Within a year, he contracted typhoid and returned to France to recover.

During this period, Monet encountered Johan Barthold Jongkind, a Dutch painter known for his land and seascapes. Jongkind became what Monet later described as his “true master…the final education of my eye.” His influence was transformative—encouraging Monet to perceive nature not merely as subject matter, but as atmosphere, as light in motion.

A Deal and a New Direction

Monet’s devoted aunt, Mme Lecadre, remained convinced of his talent. She offered to buy him out of the army, and a compromise was reached with Adolphe: Claude would receive a modest allowance to study art in Paris, provided he enrolled in a formal atelier.

Monet chose the studio of Charles Gleyre, a Swiss painter known for his landscape interests and his training of students for the Prix de Paysage Historique. Gleyre’s atelier was affordable—charging only for models and materials, not instruction—which suited Monet, whose father kept him on a strict budget.

The Birth of a Brotherhood

In 1862, Monet began his studies at Gleyre’s atelier and quickly bonded with fellow students Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille, and Alfred Sisley. Within months, Monet was leading plein-air painting excursions to the Fontainebleau Forest and the surrounding countryside.

By 1863, the French art world was in turmoil. Édouard Manet had scandalized the Salon des Refusés with Luncheon on the Grass, defying academic conventions with bold composition and modern themes. Monet, still unknown, was quietly forging his own path—rejecting Gleyre’s teachings and committing to a rigorous program of self-directed study.

When Gleyre retired in 1864, Monet—then 24—was free to chart his own course, though still financially tethered to his father. Bazille stepped in, offering not only financial support but companionship. The two shared a studio on rue Furstenberg between 1865 and 1866. Bazille’s death in the Franco-Prussian War would later prove a devastating blow—both personally and artistically.

First Successes and Artistic Evolution

By the Salon of 1865, Monet had achieved modest recognition. Two of his landscapes were accepted and exhibited, receiving mixed reviews. One critic hailed him as “a young Realist who promises much,” while another dismissed his work as immature. Yet Monet’s obsession with light and color was unmistakable. The influences of Boudin, Jongkind, Manet, and Courbet were evident, but his style was evolving—moving away from strict Realism toward something more atmospheric, more ephemeral.

During this period, Monet began experimenting with large-scale figure compositions. His own Luncheon on the Grass—never completed—was an ambitious attempt to integrate figures and natural light into a unified plein-air scene. Art historian Forge described it as an effort to “monumentalize the language of a plein-air sketch.”

Injury, Frustration, and Friendship

The project was bold, but perhaps destined to falter. Monet lacked the studio space, time, and financial stability to complete it. In 1865, he injured his leg and was confined to bed at the Cheval-Blanc Inn in Chailly, where he had been working on the painting.

Bazille, who had abandoned medicine to pursue art, used his medical knowledge to ease Monet’s discomfort—constructing a device to drip water onto the injured leg. His portrait Monet après son accident captures the artist lying in bed, impatient and irritable, awaiting Bazille’s arrival to model. More than a depiction, the painting is a testament to their deep friendship and Bazille’s unwavering support.

This chapter in Monet’s life is a study in contrasts: defiance and dependence, ambition and limitation, solitude and solidarity. It marks the emergence of a painter who would soon redefine the language of light—and the dawn of a movement that would reshape the course of art history.

Struggle, Love, and Artistic Resolve (1867–1871)

By 1867, Claude Monet’s life was unraveling. His relationship with Camille-Léonie Doncieux—his model, muse, and lover—had drawn the ire of both his father, Adolphe, and his aunt, Mme Lecadre. Camille had posed for several figures in Luncheon on the Grass and for Monet’s ambitious new canvas Women in the Garden, which was ultimately rejected by the Salon. Their romance, already strained by financial instability, was now under siege from their families.

Monet was drowning in debt. Camille was pregnant. The modest 800 francs he had earned from the Salon of 1866 had long since vanished. Under pressure from Aunt Lecadre and Adolphe, Monet was forced to retreat to Sainte-Adresse on the Normandy coast. Camille remained in Paris, where she gave birth to their son Jean in July—alone, ill, and destitute.

In a letter to Bazille that May, Monet confessed his despair: Camille was “ill, bedridden and penniless,” and he didn’t know what to do. He reminded Bazille of a fifty-franc debt due by the first of the month. Bazille, ever loyal, bought Women in the Garden for 2,500 francs—payable in monthly installments. But Monet’s desperation deepened. In June, he asked for another 100 or 150 francs. By August, he wrote a heartbreaking plea: “Really, Bazille… there are things that can’t be put off until tomorrow. This is one of them and I’m waiting.”

Sainte-Adresse and the Maturing Eye

Despite the emotional turmoil, Monet’s enforced stay at Sainte-Adresse yielded a series of beach scenes that revealed a growing maturity in his vision. The brilliant sunlight, however, caused severe eye strain, forcing him to stop painting that autumn.

The following year brought mixed fortunes. Monet sold a full-length portrait of Camille—Woman in the Green Dress—to Arsène Houssaye, editor of L’Artiste, and received a commission to paint Mme Gaudibert, the wife of a Le Havre notable. Yet creditors seized his paintings at an exhibition in Le Havre, and the strain on his relationship with Camille, now caring for a newborn, was immense.

In June 1868, the family was evicted from a country inn. Monet, overwhelmed, confessed in a letter to Bazille that he had attempted suicide. Whether this was a genuine act or a dramatic expression of despair is unclear—Monet’s letters often veered into bathos. But the pain was real.

By December, the tide had turned. Thanks to the patronage of M. Gaudibert, Monet, Camille, and Jean were living in a small cottage in Etretat. Monet was ecstatic. “Surrounded by my family and able to work in peace,” he wrote to Bazille. Reflecting on his art, he added: “The further I get, the more I realize that no one ever dares give frank expression to what they feel.”

The Birth of Impressionism

In the summer of 1869, Monet began to do just that. Working alongside Renoir at La Grenouillère on the Seine, he produced what are now considered the first truly Impressionist paintings. Monet dismissed them as “rotten sketches,” but signed them nonetheless. They were studies for a larger, now-lost canvas—known only through a faint photograph—but the surviving works reveal the essence of the movement: fluid brushwork, fleeting light, and atmospheric immediacy.

At this point, the distinction between sketch and finished painting was beginning to dissolve. Monet was painting wet-on-wet, using swift, confident strokes to blend color directly on the canvas. This technique matured in Trouville the following summer and reached new heights during his exile in London from 1870 to 1871.

Exile and Reinvention in London

Monet had just married Camille when the Franco-Prussian War broke out. To avoid conscription, he fled to London. The city was unfamiliar, its climate mercurial, its fogs legendary. “I endured much poverty,” he recalled in 1900. Yet London offered new challenges—and new allies.

There, Monet reconnected with Pissarro and Daubigny, fellow exiles, and met the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. Their relationship, forged in hardship, would last a lifetime. Durand-Ruel became Monet’s most important patron, championing his work through decades of ups and downs.

London’s mists, parks, and river scenes presented a new set of atmospheric problems for Monet to solve. He embraced them with fascination and frustration—emotions he would revisit when he returned to London more than thirty years later to paint its fog-shrouded bridges and Parliament.

This chapter in Monet’s life is a crucible of emotion and innovation. Personal hardship, romantic devotion, and artistic daring collided to produce the first glimmers of Impressionism. Through it all, Monet remained true to his vision—painting not what he saw, but what he felt.

“My first thought was that I was done for. My boots, stockings and coat were soaked through… the palette had hit me in the face and my beard was covered in blue and yellow… the worst thing was that I lost my painting which soon disintegrated along with the easel.”

It was a moment of chaos, but also of commitment. Monet’s willingness to risk physical harm for the sake of a canvas speaks to the depth of his artistic obsession.

This chapter in Monet’s life is a study in resilience. Amid personal loss, financial instability, and artistic tension, he continued to expand his vision—seeking not just to paint what he saw, but to capture the very sensation of seeing.

Color Unbound: The Mediterranean and Monet’s Emotional Palette

For an artist like Claude Monet—whose sensitivity to color had been honed in the muted, often melancholic landscapes of northern France—the Mediterranean presented a visual shock. The intense blues of sea and sky were, at first, “appalling” and “beyond me,” he admitted. But the challenge of mastering this new light became a turning point. By the 1880s, Monet’s palette had shed its lingering ties to naturalistic color. His canvases—such as Rocks at Belle-Île and Poppy Fields at Giverny—were worked and reworked with thick, vivid pigment, transforming color into a language of emotion.

These paintings were no longer mere impressions of light—they were expressions of feeling, of memory, of the artist’s psychological relationship to the landscape. Monet had begun to paint not just what he saw, but what he felt.

The Meules Series and the Rise of Serial Vision

Following the death of Ernest Hoschedé in 1892, Monet withdrew from extensive travel and refocused on the familiar landscape surrounding his home. Driven by an obsession with capturing the “fugitive effect”—those elusive moments when light and atmosphere converge—he began painting multiple canvases simultaneously, each attuned to a specific condition of light.

The first major fruit of this method was the Meules (Grain Stacks) series, begun in the mid-1880s and exhibited at Durand-Ruel’s gallery in 1891. These were not mere haystacks, but stacks of wheat and oats—ordinary rural forms transformed into extraordinary visual phenomena.

The series was a sensation. Pissarro, somewhat exasperated, wrote to his son Lucien about the frenzy it caused. Collectors, especially in America, paid thousands of francs for each canvas. Yet beyond its commercial success, the series marked a philosophical turning point. Monet was no longer painting objects—he was painting time, perception, and presence. As Kandinsky later observed, Monet’s abstraction through repetition became a defining feature of his late style.

This approach continued in subsequent series: Poplars (1891), Rouen Cathedral (1894), and Mornings on the Seine (1896–97)—each a meditation on rhythm, light, and the dissolution of form.

London, Venice, and the Final Travels

In the late 1890s and early 1900s, Monet embarked on his final major journeys. He returned to London, where by 1904 he had painted over 100 views of the Thames—capturing the city’s fog, bridges, and Parliament in a haze of color and atmosphere. In 1908, he traveled to Venice, producing luminous depictions of canals and palazzos that shimmer with reflection and reverie.

These were not travel souvenirs. They were philosophical inquiries into the nature of perception itself—visual meditations on how light transforms space and memory.

Giverny: The Garden as Vision

With his paintings now commanding high prices, Monet was finally able to realize a lifelong dream: to create a living canvas. He purchased land adjacent to his home in Giverny, diverted a stream, and built a water garden complete with a Japanese bridge. Over time, the garden blossomed into a floral wonderland—a monumental orchestration of color, form, and seasonal change.

“What I need most of all are flowers, always, always,” he once said.

His attention turned to the waterscape of the lily pond. The Nymphéas (Water Lilies) series became his obsession. “These landscapes of water and reflections have become an obsession,” he told Geffroy in 1908. “It’s quite beyond my powers at this age, but I need to succeed in expressing what I feel.”

In 1909, forty-eight of these canvases were exhibited at Durand-Ruel’s gallery. They were not simply paintings—they were immersive environments, precursors to installation art, and expressions of pure visual meditation.

The Décorations: A Gift to France

Encouraged by Georges Clemenceau, Monet envisioned a monumental cycle of Water Lilies to be donated to the French state. The plan was ambitious: a series of massive canvases to be housed in a specially designed oval room. The Orangerie near the Louvre was selected as the site, though political and logistical hurdles made the project seem, at times, impossible.

In 1911, Alice Monet died. In 1914, his son Jean passed away. Monet, now seventy-four, was cared for by his stepdaughter Blanche Hoschedé-Monet. Despite grief and declining health, he pressed on.

To accommodate the scale of the Décorations, Monet proposed building a new studio. As World War I raged, he oversaw its construction and continued working in his old studio. Cataracts clouded his vision, making color difficult to discern. In frustration, he destroyed several canvases. An operation in 1923 restored partial sight, allowing him—at eighty-three and dying of cancer—to nearly complete the cycle.

The Final Light

Monet died on December 5, 1926, a month after his eighty-sixth birthday, with Clemenceau at his side. He lived just long enough to see the completion of his final masterpiece—a gift to France, the culmination of decades devoted to light, nature, and the fleeting moment.

Geffroy wrote of the lily pond:

“There he found, as it were, the last word on things, if things had a first and last word. He discovered and demonstrated that everything is everywhere, and that after running round the world worshipping the light that brightens it, he knew that this light came to be reflected in all its splendour and mystery in the magical hollow surrounded by the foliage of willow and bamboo, by flowering irises and rose bushes through the mirror of water from which burst strange flowers which seem even more silent and hermetic than all the others.”

The Last Canvases

In his final years, Monet returned to the Japanese bridge and the garden at Giverny. These late works are marked by violent, feverish brushstrokes—an inferno of color, a last challenge to sunlight. They are not quiet reflections, but bold declarations. The Impressionist who once sought to capture the fleeting now painted with urgency, as if racing against time itself.

Six months before his death, Monet wrote:

“...in the end the only merit I have is to have painted directly from nature before the most fugitive effects, and it still upsets me that I was responsible for the name given to a group, most of whom had nothing Impressionist about them...”

Monet outlived two wives, a son, the Second Republic, the Second Empire, and all his contemporaries—Pissarro, Degas, Renoir. His work was celebrated across the globe, commanding enormous prices. But his true legacy lies not in fortune, but in vision: a lifelong pursuit of light, color, and truth.

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.

Monet Crossword Puzzle

Instructions

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.

PC instructions; left click in the word space you want. Then type with your keyboard.

Mobile instructions: touch the word space you want to fill in. Then touch the little black squares at the bottom of the screen. That will bring up your keyboard. Type in the word.

Click Image