Wassily Kandinsky

Composition X, 1936

Composition X - 2

Composition X - 3

Composition X - 4

Sans Titre 1910-1913

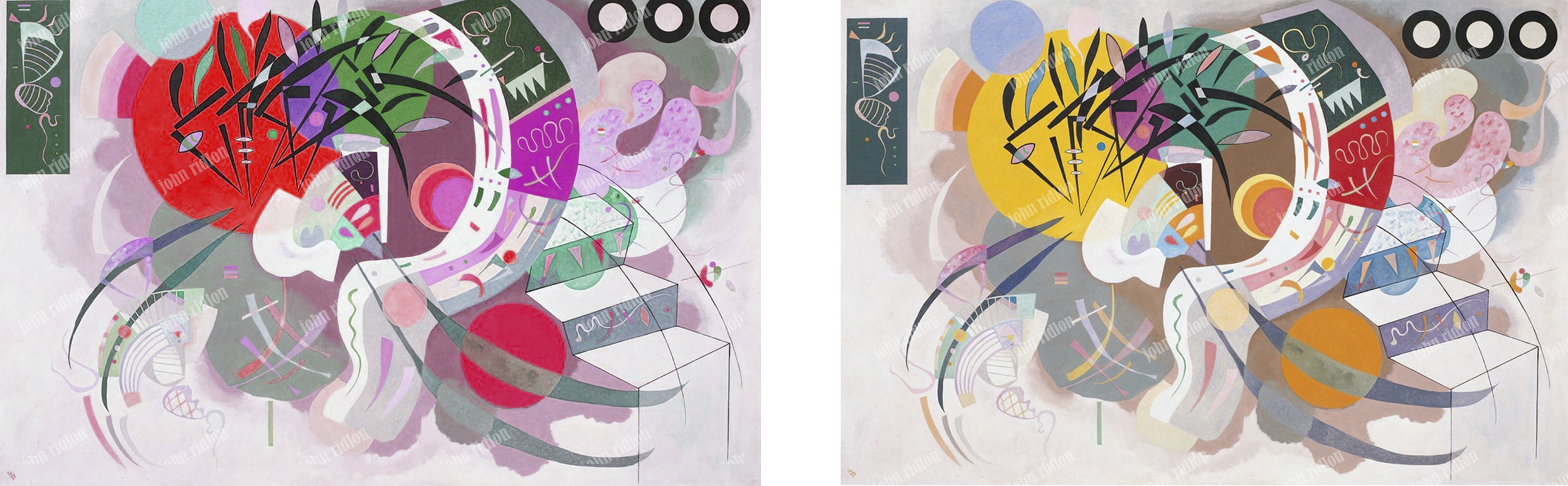

Dominant Curve

Dominant Curve 2

Dominant Curve 3

Dominant Curve 4

Three Pillars 1, 1943

Three Pillars 2

Three Pillars 3

Three Pillars 4

Painting with Three Spots 1914

Painting with Three Spots 1914 4

Squares with Concentric Circles 2

Squares with Concentric Circles, 1913

Squares with Concentric Circles 3

Squares with Concentric Circles 4

In the Bright Oval,, 1925

In the Bright Oval 2

In the Bright Oval 3

In the Bright Oval 4

Composition 1, 1914

Composition 2, 1914

Composition 3, 1914

Composition 4, 1914

The Red Knot 1936

Various Actions 1913

Composition 6, 1913

Fragments, 1943

Launisch, 1930

Yellow-Red-Blue, 1925

Snowy Landscape (1866-1944)

Impression III (Concert), 1911

Blue Segment 1921

blue circle, 1922

Autumn Landscape, 1908

In Blue, 1925

View from the Window of Griesbrau, 1908

Autumn

Composition 7

Bright Unity

The Biography of Vasily Kandinsky

Vasily Kandinsky: Architect of the Abstract Spirit

Vasily Kandinsky was more than a painter—he was a visionary thinker, a passionate educator, a cultural organizer, and a spiritual provocateur. His legacy in modern art rests not only on his pioneering abstract compositions but on his conviction that painting could serve as a conduit for the soul. Through decades of experimentation, writing, and teaching, Kandinsky redefined the purpose of art: not as a reflection of the external world, but as a language of inner necessity—a visual symphony of emotion, intuition, and metaphysical resonance.

A Late Start, A Lifelong Calling

Born in Moscow in 1866 and raised in the port city of Odessa, Kandinsky displayed an early sensitivity to color, music, and form. Yet he initially pursued a conventional path, earning degrees in law and economics and establishing a promising academic career. It wasn’t until the age of 30 that he made a radical pivot—abandoning legal scholarship to study painting in Munich. This decision was not impulsive, but the result of a quiet, persistent inner calling that refused to be ignored.

In Munich, Kandinsky entered art school as a mature student among younger peers. Despite his technical inexperience, his intellectual depth and philosophical insight quickly earned him respect. He became a teacher at the Phalanx school, where he fostered a community of progressive artists and thinkers. His early works—landscapes, urban scenes, and seasonal studies—were modest in scale and rooted in traditional techniques. Yet even in these early pieces, Kandinsky painted from memory rather than direct observation, signaling a shift toward internal vision and emotional truth.

Travel and Transformation

Between 1900 and 1908, Kandinsky embarked on a period of prolific creation and wide-ranging travel. He produced hundreds of works while journeying through Europe and North Africa, absorbing the visual rhythms of each place. His paintings from this era—windswept beaches in Holland, sun-drenched seascapes in Italy, and glowing vistas from Tunisia—reveal a growing confidence and complexity in his style.

During these travels, Kandinsky began to incorporate figures into his compositions, including romantic portrayals of horsemen and intimate portraits of Gabriele Münter, his student, companion, and artistic confidante. Their relationship was both personal and creative, and Münter’s influence can be felt in Kandinsky’s evolving palette and compositional daring.

These years were a crucible of experimentation. Kandinsky engaged with Impressionism’s light, Neo-Impressionism’s color theory, Fauvism’s boldness, and Art Nouveau’s decorative elegance. Yet he remained discerning, adopting only what resonated with his inner vision. His work from this period reflects a synthesis of external influences and internal revelation—a bridge between the seen and the

The Murnau Breakthrough

In 1908, Vasily Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter settled in Murnau, a quiet village nestled in the Bavarian Alps. This move marked a profound turning point in Kandinsky’s artistic evolution. Surrounded by alpine light and folkloric architecture, his landscapes began to shift—no longer descriptive, but expressive. Brushstrokes loosened, colors intensified, and natural forms dissolved into autonomous shapes and rhythmic patterns. Nature was no longer a subject to be depicted—it became a catalyst for abstraction.

By 1910, Kandinsky had completed the first of his Compositions—a series of ten monumental paintings he regarded as visual summations of his spiritual and artistic journey. These works abandoned narrative and representation entirely, channeling emotional and metaphysical realities through pure form. He did not reject nature; he transcended it. Abstraction, for Kandinsky, was not a stylistic choice—it was a spiritual imperative.

The Blue Rider and the Rise of Theory

Kandinsky’s influence extended far beyond the studio. In 1909, he became president of the New Artists’ Association in Munich, a group committed to progressive art. But ideological tensions soon surfaced. Kandinsky’s radical vision—rooted in spiritual abstraction—clashed with the group’s lingering conservatism. In 1911, he resigned and, alongside Franz Marc, co-founded Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), a short-lived but legendary initiative that reshaped the trajectory of modern art.

The Blue Rider was not a movement in the conventional sense. It was a platform for dialogue, diversity, and cross-cultural exchange. It embraced folk art, children’s drawings, music, and non-Western traditions. Kandinsky’s own paintings reflected the influence of Bavarian glass painting and other vernacular forms, while the group’s exhibitions revealed a shared sensibility among artists like Münter, Alexej von Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin, August Macke, Franz Marc, and Paul Klee.

In 1912, the Blue Rider Almanac was published—a landmark in art theory and interdisciplinary thought. Kandinsky’s essays, especially “On the Question of Form,” challenged the binary between abstraction and realism. He argued that both were valid paths when guided by “inner necessity”—a term he used to describe the authentic impulse that drives true artistic creation. He envisioned a spiritual reawakening through art, one that transcended materialism and rationalism.

Kandinsky also proposed a new kind of stage composition—one that fused music, color, and movement into a unified sensory experience. His theatrical scenario The Yellow Sound was a prototype for modern multimedia performance, anticipating developments in experimental theater, synesthesia, and installation art.

On the Spiritual in Art

Written in 1910 and published in 1911, Kandinsky’s treatise On the Spiritual in Art remains one of the most influential texts in modern aesthetics. In it, he argued that art must be rooted in inner necessity—not in external rules, academic formulas, or market trends. Form, he insisted, was not an end in itself but a vessel for spiritual intent.

Drawing analogies from music, Kandinsky dismissed the notion of “dissonance” as arbitrary. What mattered was the authenticity of the artist’s inner voice—the resonance between the soul and the image. He believed that colors, shapes, and lines could evoke emotional states and spiritual truths, much like musical notes stir feeling without words.

This treatise laid the philosophical foundation for abstraction as a legitimate and profound artistic language. It was not a rejection of tradition—it was a renewal of purpose. Kandinsky saw the artist as a prophet, a visionary, a translator of the invisible

Moscow and the Russian Avant-Garde

Kandinsky’s return to Moscow in 1916 placed him at the epicenter of seismic cultural and political transformation. The Russian Revolution was reshaping every facet of society, and Kandinsky—ever attuned to the spirit of change—immersed himself in the evolving artistic landscape. He joined the People's Commissariat of Enlightenment (Narkompros), a progressive institution tasked with democratizing culture and education. Working alongside radical figures like Vladimir Tatlin, he helped promote contemporary art through newly established, state-funded museums and exhibitions.

In 1920, Kandinsky co-founded Inkhuk—the Institute of Artistic Culture—a think tank for avant-garde theory and practice. But ideological tensions quickly surfaced. Kandinsky’s belief in the spiritual and emotional dimensions of art clashed with the emerging Constructivist ethos, championed by younger artists like Aleksandr Rodchenko. For Rodchenko and his peers, art was to be functional, rational, and socially utilitarian. Kandinsky, by contrast, saw abstraction as a path to transcendence—a way to access inner truths beyond material form.

Though his artistic output during this period was modest, the years in Moscow were marked by intense intellectual reflection and personal upheaval. His separation from Gabriele Münter, his marriage to Nina Andreevskaia, and the tragic loss of his young son added layers of emotional complexity to an already turbulent time. Yet by the early 1920s, Kandinsky’s paintings began to exhibit renewed clarity. Defined geometric shapes—especially the perfect circle—emerged as recurring motifs, signaling a shift toward a more structured, symbolic visual language.

The Bauhaus Years: Geometry and Synthesis

In 1922, Kandinsky accepted an invitation to join the Bauhaus, the revolutionary school of art, design, and architecture founded by Walter Gropius. Initially based in Weimar and later relocated to Dessau, the Bauhaus emphasized functional design and the integration of art into everyday life. Though the school’s focus leaned toward applied arts, Kandinsky was eventually granted the freedom to teach painting on his own terms.

This period marked a creative renaissance. Kandinsky’s output surged, and his style evolved into a more geometric and analytical abstraction. He began to explore the interplay between form and space with mathematical precision, using circles, triangles, and lines to construct visual harmonies. His compositions often featured vertical subdivisions, creating dynamic contrasts between color fields, textures, and spatial rhythms.

In 1926, Kandinsky published Point and Line to Plane, a seminal treatise that codified his theories of visual structure. Drawing on musical analogies and spiritual philosophy, the book examined how basic elements—points, lines, and planes—could be orchestrated to evoke emotional resonance and compositional balance. It was not just a manual for abstract art—it was a manifesto for a new visual language rooted in inner necessity and universal form.

Circle became central icons, replacing earlier figurative motifs. Shapes floated in space, intersected, and merged into rhythmic compositions. His titles shifted from descriptive to poetic—Blue Painting, Pink Square, Capricious, Brown Silence. The Bauhaus years marked a consolidation of his abstract language—rigorous yet expressive, systematic yet mysterious.

But the political climate grew hostile. The Bauhaus was attacked by right-wing factions and eventually shut down in 1933. Kandinsky, holding on longer than most, finally left Germany and settled in Paris.

Final Years in Paris: Biomorphic Renewal

In Paris, Kandinsky entered a new phase. Living quietly in Neuilly-sur-Seine, he remained independent from Cubism and Surrealism, though he found inspiration in scientific illustrations and microscopic forms. His geometric base softened, giving way to biomorphic shapes—amoebas, moons, and floating organic forms.

Works like Graceful Ascent and Poker Orange revealed a new sensibility: slower rhythms, aqueous textures, and playful intimacy. Titles like Sweet Trifles and An Intimate Celebration reflected this shift. He began naming works in French, just as he had used German during his Bauhaus years.

This final chapter of Kandinsky’s life was one of quiet innovation. His art became more tactile, more humorous, and more alive—anchored not in celestial abstraction, but in the hidden worlds of nature.

To explore Kandinsky’s work and other pioneers of abstraction, visit masterworksprints.com.

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.

Kandinsky Crossword Puzzle

Click on Image