Marcel Duchamp

Network of Stoppages, 1914

Chocolate Grinder (No. 1), 1913

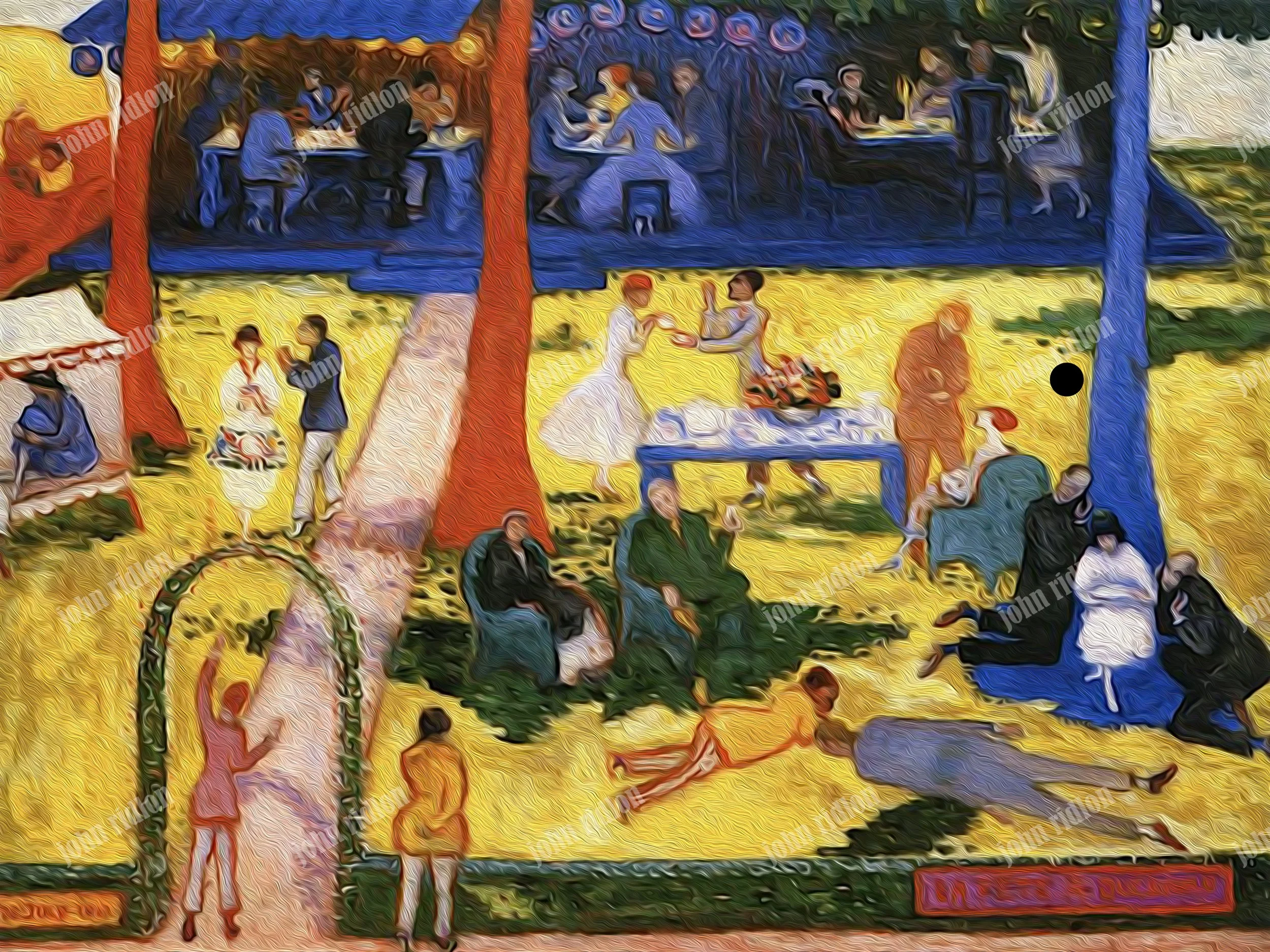

Florine Stettheimer, La Fete, 1917

Portrait of a Man, 1913

Katherine Sophie Dreier

Chocolate Grinder No. 2

The Biography of Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp: Art as Thought, Irony, and Provocation

Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) remains one of the most radical and influential figures in twentieth-century art. Often described by Willem de Kooning as a “one-man movement,” Duchamp’s work bridged visual art, literature, and philosophy, embodying the cerebral spirit of contemporaries like Marcel Proust and James Joyce. Jasper Johns once called his practice “the field where language, thought and vision act on one another”—a fitting description for an artist who sought to liberate art from mere visual pleasure and return it to the realm of intellectual inquiry.

By the time of World War I, Duchamp had grown disenchanted with what he called “retinal” art—works designed only to please the eye. His mission was clear: “to put art back in the service of the mind.” This shift marked the beginning of a lifelong pursuit of irony, conceptual rigor, and philosophical provocation.

From Normandy to New York: A Journey of Reinvention

Born in Normandy, Duchamp spent much of his life moving between Europe and the United States. His early paintings followed the Impressionist and Cézanne-inspired trends of the time, but by 1910, his work began to shift toward Cubism. His landmark painting Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) (1912) exemplifies this transition. While adopting Cubism’s muted palette and fractured geometry, Duchamp infused the figure with dynamic motion—breaking from the static, analytical style of Picasso and Braque.

The painting was controversial from the start. Rejected by the Salon des Indépendants for its mechanistic depiction of the female nude and provocative title, it later caused a sensation at the 1913 Armory Show in New York. The scandal surrounding the work cemented Duchamp’s reputation as a provocateur and opened the door to his eventual relocation to the United States, where he would continue to challenge the boundaries of art for decades to come.

The Readymade and the Rise of Conceptual Art

Marcel Duchamp’s most revolutionary contribution to twentieth-century art came through his invention of the readymade—ordinary, mass-produced objects designated as art simply by the artist’s selection and intent. His first, Bicycle Wheel (1913), combined a wheel and a stool into a sculpture that defied traditional notions of craftsmanship and aesthetic value. Duchamp viewed paint itself as an industrial product, once referring to painting as an “assisted-readymade.” In this light, the readymade was not a rupture with tradition, but a logical extension of modern materials and thought.

He also embraced chance as a creative force. In 3 Standard Stoppages (1913–14), Duchamp introduced randomness into the artistic process, allowing accident and unpredictability to shape the final result. His goal was to shift emphasis away from technical skill and toward conceptual depth—inviting viewers to engage with irony, wordplay, and philosophical paradox rather than visual beauty or formal mastery.

Later readymades included a snow shovel, a bottlerack, and most famously, Fountain (1917)—a porcelain urinal submitted under the pseudonym “R. Mutt” to a New York exhibition. These works challenged the boundaries of taste, authorship, and artistic legitimacy, transforming industrial detritus into cultural critique. Duchamp’s readymades were not just objects—they were provocations, designed to question the very definition of art.

Dada, Satire, and the New York Circle

Duchamp’s iconoclasm found resonance within the Dada movement, which emerged in response to the devastation of World War I and the collapse of European rationalism. While European Dada was overtly political and anarchic, Duchamp’s version—developed in New York alongside Francis Picabia, Man Ray, and patrons like Katherine Dreier and the Arensbergs—was more satirical, cerebral, and conceptually driven.

In this circle, Duchamp helped redefine the role of the artist—not as a craftsman or romantic genius, but as a thinker, a strategist, and a cultural saboteur. His work blurred the lines between art and philosophy, object and idea, joke and manifesto. Through wit, irony, and intellectual rigor, Duchamp laid the foundation for conceptual art and reshaped the trajectory of modernism.

Duchamp’s works from this period, especially Fountain, tested the boundaries of public perception and institutional authority. Through puns, alliteration, and layered humor, he critiqued not only the art world but also the broader political and economic systems of his time. His readymades were not simply provocations—they were philosophical statements, challenging the very premise of authorship, originality, and aesthetic value.

The Large Glass and the Breakdown of Form

Between 1915 and 1923, Duchamp worked on The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even—better known as The Large Glass. This enigmatic piece, now housed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, encapsulates Duchamp’s belief that traditional painting and sculpture were inadequate for expressing the complexities of modern life. Composed of glass, dust, and mechanical imagery, the work reflects his shift toward abstraction, mathematical symbolism, and conceptual layering.

His preparatory notes and diagrams—later compiled in The Green Box (1934)—reveal a meticulous intellectual framework that blurred the line between art and literature, object and idea. The Large Glass stands as a manifesto against realism and a celebration of intellectual play, inviting viewers to decode its cryptic mechanics and embrace ambiguity as a form of insight.

Chess, Legacy, and the Artist as Trickster

In the 1920s, Duchamp famously declared his retirement from art to pursue chess full-time. Yet this retreat was more theatrical than literal. He continued to shape the art world through quiet interventions, collaborations, and conceptual provocations—maintaining his role as the archetypal artist-trickster. His presence lingered in exhibitions, conversations, and the evolving discourse of modernism.

Duchamp’s legacy spans Cubism, Dada, Surrealism, and beyond. His ideas laid the groundwork for Pop Art (Andy Warhol), Minimalism (Robert Morris), and Conceptualism (Sol LeWitt). More than any single style or object, Duchamp’s enduring contribution is his permission—indeed, his insistence—that artists challenge norms, question meaning, and redefine what art can be.

He didn’t just change the rules. He made it clear that the rules were always negotiable—and that the most radical gesture might be to laugh at them.

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.

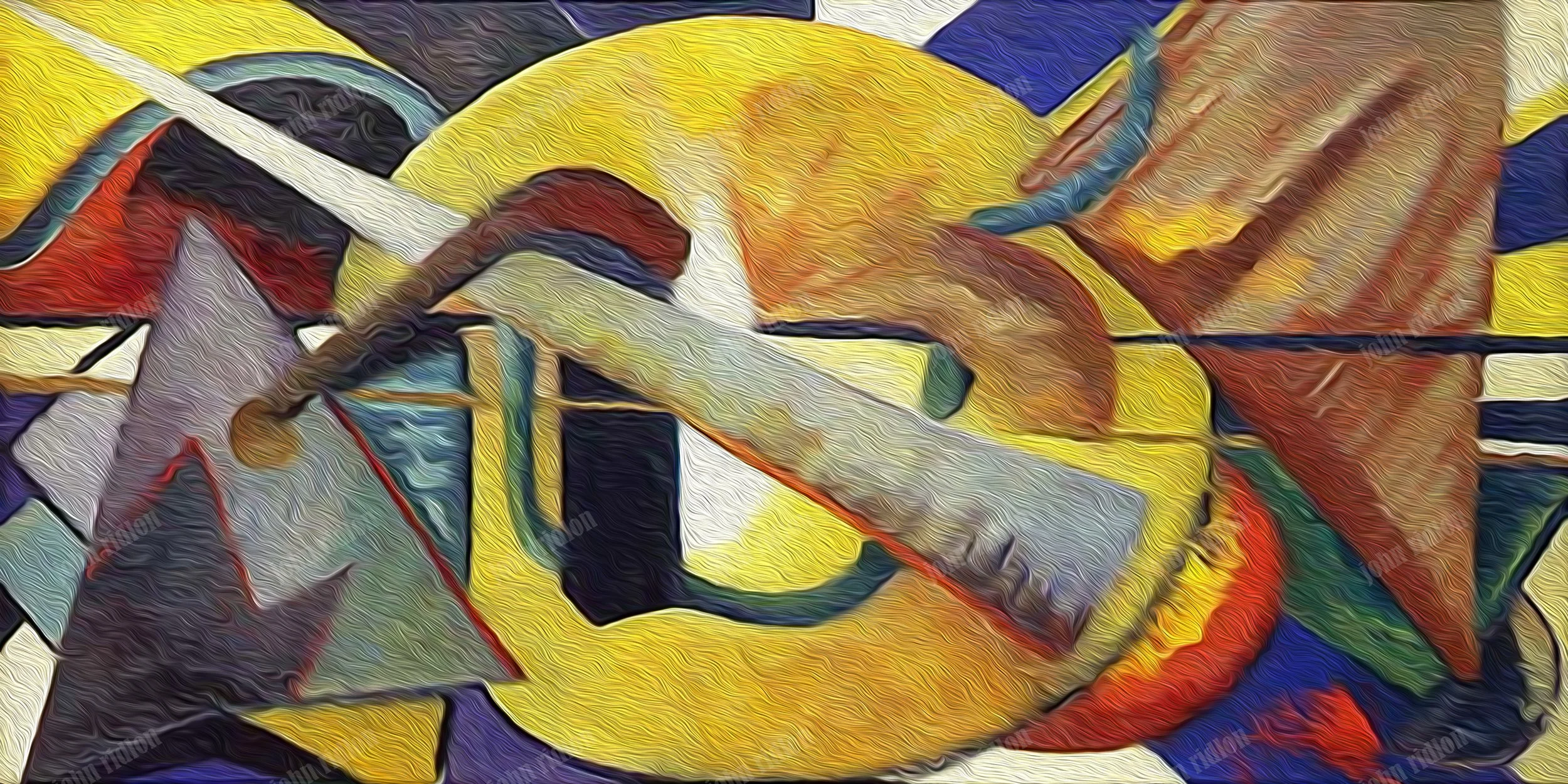

Duchamp Crossword Puzzle

Click on Image