Paul Gauguin

Sacred Spring, Sweet Dreams, 1894

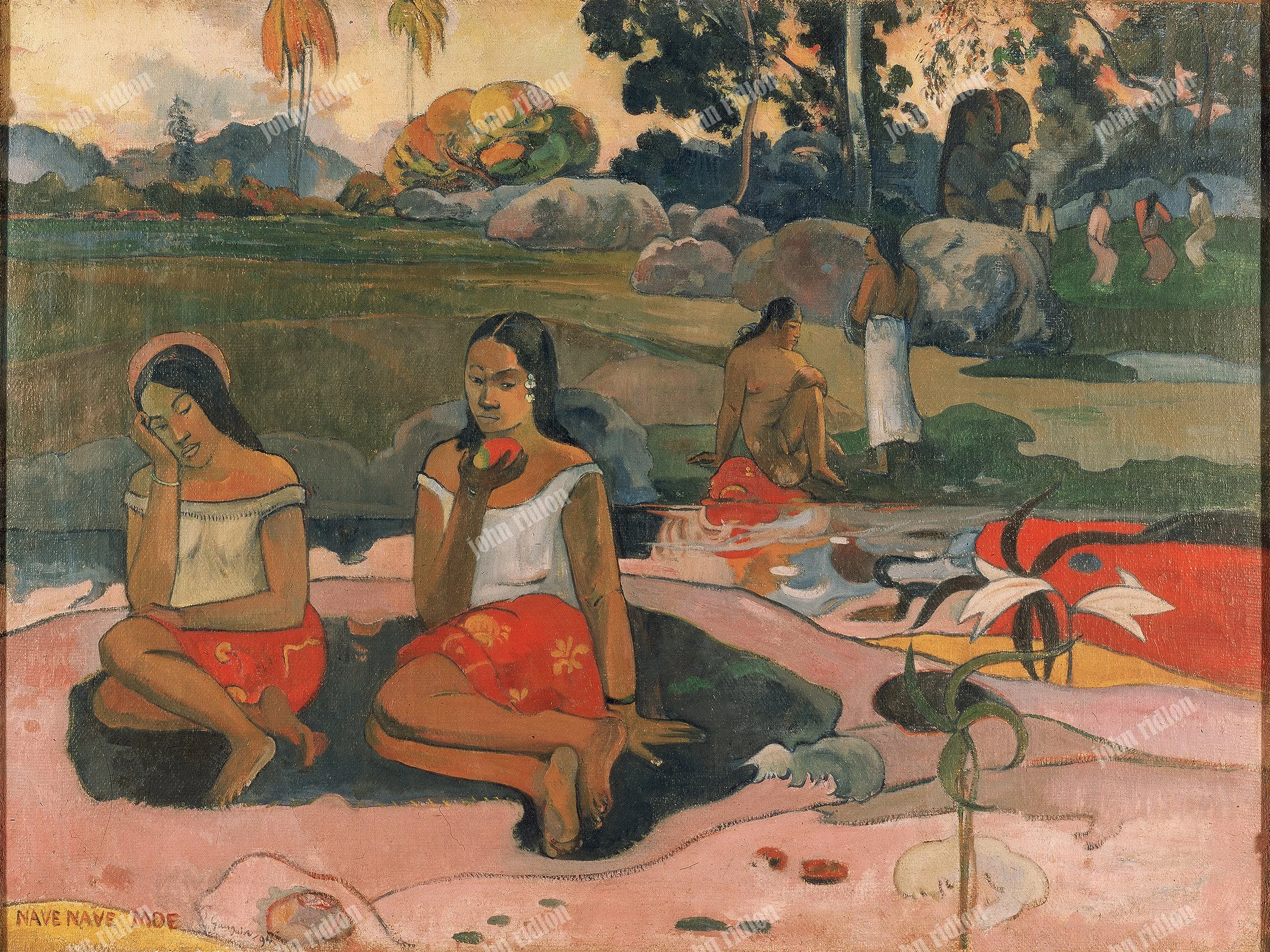

Nave Nave Moe, 1894

The Large Tree, 1892

Portrait of Two Children, 1889

Mrs Vornehme 1896

The Month of Mary, 1899

Still Life with Profile of Laval, 1886

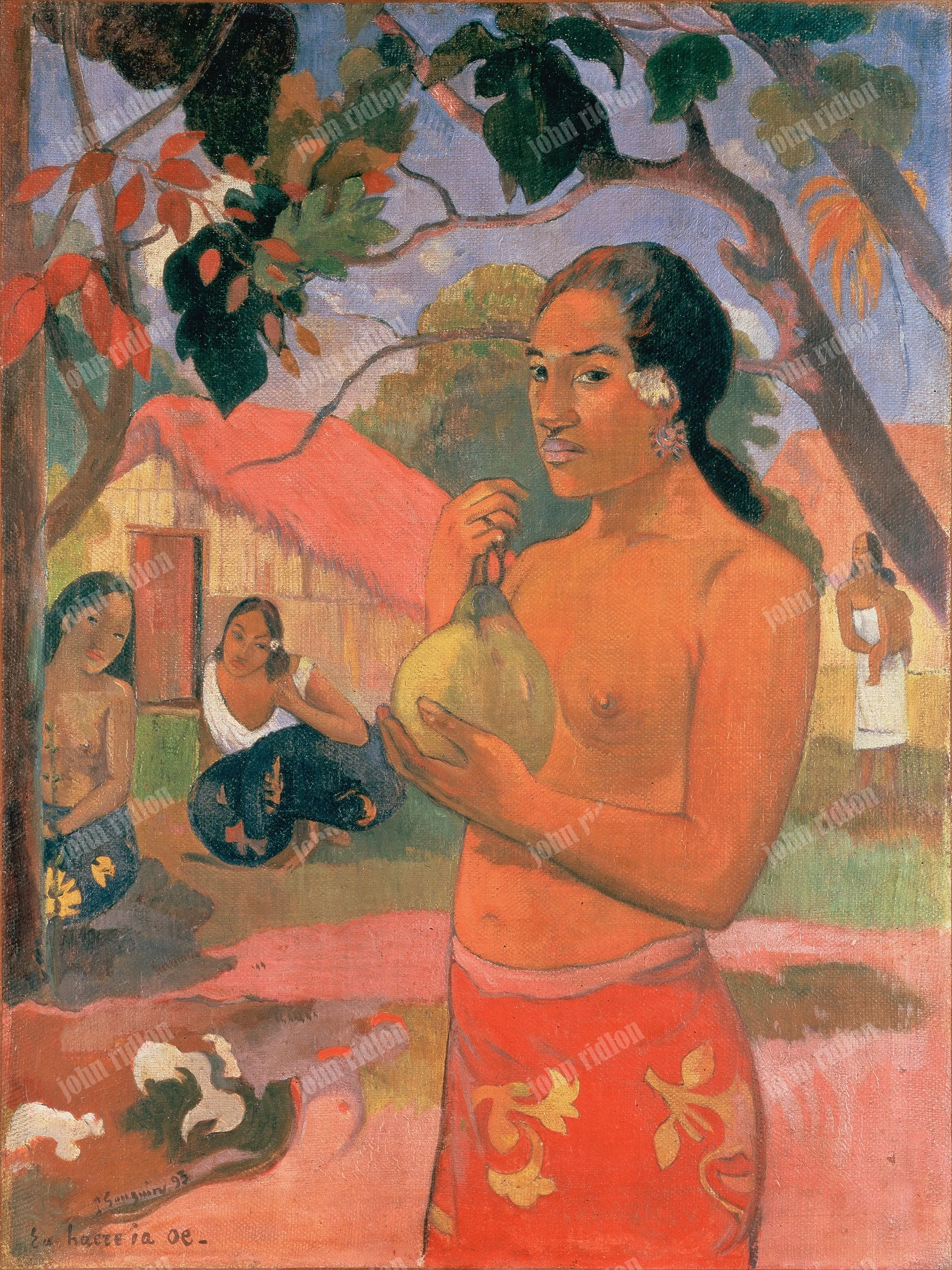

Woman Holding a Fruit, 1893

Roses and Statuette, 1889

Nafea Faa Ipoipo, 1892

Three Tahitian Women,1896

Te Tiare Farani, 1891

Still Life with Exotic Birds, 1902

Mahana no Atua, 1894

Mahana no Atua, 1894-2

The Ford (The Flight),1901

The Flageolet Player on the Cliff, 1889

Biography of Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin: From Impressionist Apprentice to Symbolist Visionary

Paul Gauguin remains one of the pivotal figures in the shift from the fleeting observations of Impressionism to the more introspective and symbolic directions of modern art. Although he began his career within the Impressionist circle—absorbing its emphasis on light, atmosphere, and everyday life—he quickly became restless. By the late 1880s, as Impressionism was reaching maturity, Gauguin sought a more profound means of expression. His pursuit of bolder color harmonies, flattened forms, and decorative compositions marked the beginning of his journey toward Symbolism, a movement that placed emotional and spiritual truth above mere visual description.

A decisive moment came with his short yet intense collaboration with Vincent van Gogh in Arles. The summer they spent working side by side in the luminous southern light of France was as volatile as it was productive. Their differing temperaments eventually led to rupture, but the encounter catalyzed Gauguin’s break from both Van Gogh and the constraints of European society. Having already abandoned his successful career as a stockbroker, he committed himself fully to art—and to a new existence outside the cultural boundaries of the West.

His subsequent travels to Tahiti and other islands of French Polynesia transformed his artistic identity. There, Gauguin developed a style that combined direct observation with myth, memory, and spiritual symbolism. Drawing on the visual languages of Africa, Asia, and Oceania, he created works that did more than borrow motifs—they attempted to channel universal truths about nature, existence, and the human soul. By rejecting the values of European domesticity, commerce, and academic art, Gauguin fashioned himself as a visionary outsider, a mystic wanderer in search of authenticity.

Artistic Achievements and Philosophical Pursuits

Gauguin’s early command of Impressionist technique gave him a technical foundation, but it was his experimentation that pushed him toward innovation. He studied contemporary theories of color perception and visual psychology, investigating how the eye interprets light, hue, and form. His journeys—to Brittany, the Caribbean, and ultimately Polynesia—immersed him in environments that were both visually striking and spiritually charged, each feeding into his evolving artistic vocabulary.

This path culminated in what he termed synthetic painting: an approach that privileged the symbolic and emotional resonance of a scene over faithful realism. Gauguin’s canvases became meditations on universal themes: the fragility of life, the search for transcendence, and the possibility of harmony between humanity and the natural world. His work reflects both a longing for purity and a critique of modernity, inspired by his perception of “authenticity” in non-Western cultures.

Within the movement later labeled Primitivism, Gauguin played a central role. The term—now regarded critically—once captured a romanticized European belief that societies untouched by industrialization were closer to spiritual truth. Gauguin embodied this ideal, though his works reveal the tensions and contradictions inherent in cross-cultural representation. His paintings are as much about European projections and desires as they are about the cultures he encountered.

Legacy of Liberation and Artistic Autonomy

By the time Gauguin broke definitively with his wife, children, and the European art establishment, he had embraced a radical independence that redefined what it meant to be an artist. His life itself became a statement of artistic freedom: the refusal to conform to conventional roles in pursuit of a singular vision. Today, Gauguin’s name evokes not only the luminous canvases he created but also the enduring myth of the artist as rebel, seeker, and exile.

For Gauguin, art was never confined to aesthetics. It was a spiritual rebellion, a philosophical inquiry, and a reimagining of the very function of painting. His works challenge viewers to look beneath surface appearances and engage with deeper symbolic and cultural meanings.

Gauguin’s Portraits: A Mirror of the Self and the World

Gauguin’s wide-ranging career—as painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, and writer—remains one of the most compelling stories in modern art. His oeuvre reflects a restless pursuit of transcendence and authenticity, fueled by his desire to break free from Western conventions. While his landscapes and Tahitian scenes are celebrated, his portraiture deserves equal recognition. It is in portraiture, perhaps more than any other genre, that Gauguin’s symbolic, psychological, and cultural concerns converge most powerfully.

Portraiture as Psychological and Mythic Terrain

To study Gauguin’s portraits is to navigate a complex field of self-invention, cultural projection, and spiritual inquiry. Unlike traditional portraits that document likeness or social rank, Gauguin’s images use human figures as vessels for archetype and allegory. His sitters—friends, lovers, or imagined beings—appear stylized, their faces enigmatic, their surroundings charged with symbolic energy.

This reflects Gauguin’s embrace of synthétisme, his conviction that art should communicate inner meaning rather than external truth. His portraits often dissolve the boundaries between the individual and the mythic, merging lived identity with religious motifs, cultural borrowings, and personal symbolism. Each portrait becomes a mirror—at once of the subject, of Gauguin himself, and of the world he sought to reinvent through art.

Cultural Hybridity and the Ethics of Representation

Gauguin’s journeys—to Brittany, Martinique, and Polynesia—were motivated by a longing to escape what he saw as Europe’s moral and cultural decline. Yet his quest for authenticity was fraught with contradictions. His portraits of Tahitian women, for example, radiate sensuality and spiritual gravity, but they also reflect colonial fantasies and orientalist tropes.

Still, Gauguin’s engagement with non-Western art was not superficial. He studied indigenous forms, absorbed their visual logics, and translated them into his own symbolic idiom. Flattened space, bold contours, and resonant color harmonies echo Polynesian cloth designs, Buddhist iconography, and other traditions. His portraits thus embody hybridity: a fusion of Western technique and non-Western inspiration that anticipated the global currents of twentieth-century modernism.

The ethical questions, however, remain pressing. Were his sitters collaborators in his vision, or subjects consumed by it? Did he honor their individuality, or subsume them into myth? These tensions continue to shape critical debates around his work and complicate his legacy.

Dialogues with Tradition and Innovation

Though often cast as a revolutionary, Gauguin was deeply engaged with European art history. His portraits borrow strategies from Renaissance composition, Romantic intensity, and Impressionist modernity. He admired Courbet’s realism, Degas’s intimacy, Manet’s audacity, and Cézanne’s structure—all influences that subtly surface in his own work.

His relationships with contemporaries were equally complex. His portraits of Van Gogh, for instance, combine tribute and critique, capturing the Dutchman’s fervor while hinting at instability. Symbolic still lifes often served as surrogate portraits, evoking absent friends or artistic mentors through charged objects.

Most revealing are Gauguin’s self-portraits, in which he appears as Christ, devil, martyr, or prophet. These images declare his ambivalence and ambition, presenting not likeness but identity in transformation. They are visual manifestos, existential declarations of the artist’s role in modernity.

The Catalogue and Its Contributions

The recent exhibition catalogues in Ottawa and London mark a milestone in Gauguin scholarship, offering the first comprehensive exploration of his portraiture. Drawing on international research, they examine Gauguin’s art from aesthetic, cultural, and philosophical perspectives. Essays by scholars such as Elizabeth Childs, Dario Gamboni, Linda Goddard, Claire Guitton, Jean-David Jumeau-Lafond, and Alastair Wright illuminate subjects ranging from Gauguin’s self-fashioning to his depictions of fellow artists like Meijer de Haan.

These studies situate Gauguin’s portraits within the shifting landscape of late nineteenth-century portraiture, a time when identity and representation were being radically redefined. They reveal how Gauguin’s symbolic strategies opened new possibilities for portraiture as a vehicle for cultural critique and personal myth-making. Newly uncovered works—such as the drawing of Jean Moréas for La Plume—further expand our understanding of the breadth and depth of his practice.

Legacy and Resonance

Ultimately, Gauguin’s portraits compel us to rethink what it means to depict a person. They insist that identity is not fixed but fluid, shaped by memory, myth, and desire. His works are not simply likenesses; they are interpretations, constructions of meaning that intertwine sitter and artist.

This vision has profoundly influenced twentieth- and twenty-first-century art. Expressionists pursued psychological depth; contemporary artists interrogate identity itself. Gauguin’s insistence on portraiture as a symbolic act reverberates in their work.

His portraits remain mirrors—sometimes clear, sometimes clouded—of human complexity. They reflect the tensions between self and other, innovation and tradition, imagination and reality. And in doing so, they affirm the enduring power of art to probe the mysteries of existence.

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.

Gauguin Crossword Puzzle

Click on Picture