Henri-Edmond Cross

The Pink Cloud, 1896

In The Pink Cloud (c. 1896), Cross captures a radiant Mediterranean sunset with bold, expressive brushwork and vibrant Neo-Impressionist color. Cypress trees frame the scene, guiding the eye to the glowing cloud, while his use of pure, complementary hues foreshadows Fauvism and influenced artists like Matisse.

The Pink Cloud, 1896 ll

The Pink Cloud, 1896 lll

The Pink Cloud, 1896 lV

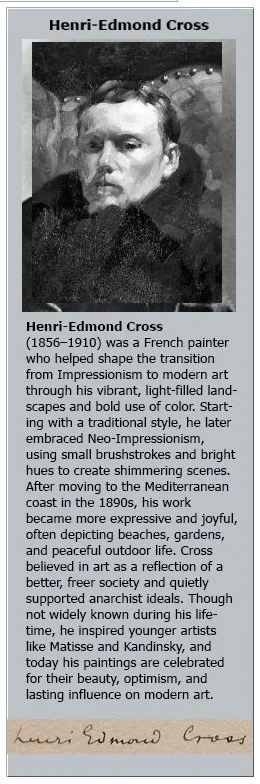

The Biography of Henri-Edmond Cross

Henri-Edmond Cross: Painter of Light, Harmony, and Utopian Vision

Henri-Edmond Cross (1856–1910) occupies a distinctive place in the history of modern painting. Though never as widely recognized as some of his contemporaries, he was a quietly radical force whose work bridged critical shifts in the art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His shimmering landscapes, suffused with radiant light and rhythmic color, embodied not only technical innovation but also an idealistic belief in beauty, harmony, and social renewal. In Cross’s canvases, art was never simply a matter of representation; it was a philosophical act, a way of imagining a world transformed by color, freedom, and utopian possibility.

Early Life and Education

Henri-Edmond-Joseph Delacroix was born on May 20, 1856, in the industrial town of Douai in northern France. His childhood was shaped by both the cultural richness and the economic struggles of the region. In 1865, when Cross was nine years old, his family moved to Lille, a city whose blend of industry and tradition provided fertile ground for his early artistic development. It was there that his talent first drew attention, nurtured by his cousin, Dr. Auguste Soins, who encouraged the young boy to pursue painting seriously.

Cross’s formal training began under the guidance of the realist painter Carolus-Duran, a demanding yet inspiring teacher who stressed precision and discipline. Later, he enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and subsequently studied at the Écoles Académiques de Dessin et d’Architecture in Lille under Alphonse Colas. These academic experiences immersed him in the established traditions of drawing, composition, and naturalistic depiction, laying a solid foundation from which his later innovations would emerge.

By 1881, Cross had settled permanently in Paris, where he began to establish himself in the city’s vibrant artistic scene. Two years later, in 1883, he chose to alter his name in order to avoid confusion with the great Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix. First anglicizing it to Henri Cross, he soon refined his signature identity to Henri-Edmond Cross—a name under which his most celebrated works would be produced.

From Realism to Radiance

In his earliest paintings, Cross worked firmly within the realist tradition. His canvases were dominated by dark palettes and conventional subjects, often reflecting the sober tones and meticulous observation characteristic of mid-19th-century painting. Yet even in these works, one senses a restlessness, a desire to break free from the weight of convention and to capture something more vital, more luminous.

The decisive turning point in his career came during the mid-1880s, when he encountered the revolutionary ideas of the Impressionists and the burgeoning Post-Impressionist movement. The freedom of their brushwork, the immediacy of their light-filled compositions, and the daring of their color experiments struck a deep chord. Cross’s artistic world widened considerably when he came into contact with Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, pioneers of Pointillism. Their systematic approach to color and optical effects offered him a new language, one both scientific and poetic, with which to reimagine the possibilities of painting.

In 1884, Cross became one of the founding members of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, a collective devoted to artistic freedom and innovation. Rejecting the rigid hierarchies of the official Salon, the group provided an unjuried platform for avant-garde painters. This commitment to independence was not merely professional but deeply ideological for Cross, who saw in it a parallel to his own belief in the liberating potential of art.

By 1891, Cross had fully embraced Divisionism, a technique in which small, distinct strokes or dots of pure color are placed side by side, allowing the viewer’s eye to perform the act of mixing. This method, though rooted in scientific theories of perception, became in Cross’s hands something more than technical precision—it became a means of creating atmosphere, rhythm, and emotional resonance. His palette lightened dramatically, moving toward brilliant hues of turquoise, gold, pink, and violet. His compositions grew expansive and dreamlike, suggesting landscapes not merely observed but idealized, transformed into visions of harmony and radiance.

Henri-Edmond Cross left Paris and moved to the small village of Saint-Clair, near Le Lavandou on the sun-soaked Mediterranean coast. This move marked a profound turning point in his career. The brilliant southern light, unlike anything he had known in northern France, transformed both his palette and his technique. Where once he had employed the tight, methodical dots of Pointillism, he now began to explore broader, mosaic-like brushstrokes, more fluid and expressive, shimmering like tesserae of color across the canvas. This evolution marked the second phase of Neo-Impressionism—less about rigid scientific application, more about harmony, decoration, and emotional depth.

His paintings from this period—sun-drenched landscapes, luminous seaside vistas, and radiant gardens—embodied an almost musical rhythm of color. They celebrated joy, serenity, and the sensuous pleasures of light itself. Yet Cross’s art was never purely decorative. Beneath the idyllic beauty lay a deeper philosophical current. He imagined in these landscapes not merely the Mediterranean as it was, but as it could be: a symbolic stage for a future anarchist utopia. His canvases became visions of freedom, community, and harmony with nature.

This utopian impulse was shared by his close friend Paul Signac, who captured a similar dream in his vast canvas originally titled Au Temps d’Anarchie (In the Time of Anarchy), later retitled Au Temps d’Harmonie (In the Time of Harmony). Both artists envisioned a society defined by collective labor freely chosen, the joys of leisure, and a liberated love of life—an ideal in which art and beauty would permeate daily existence.

Cross’s own contribution to this dream found sublime expression in his 1894 painting L’Air du Soir (The Evening Air), a canvas suffused with serenity, glowing with the suggestion of communal bliss and spiritual calm. But his commitment extended beyond the studio. A devoted supporter of the anarchist cause, he contributed illustrations to Les Temps Nouveaux (New Times), the influential paper edited by Jean Grave. His designs appeared on the 1899 cover of Élisée Reclus’s pamphlet À Mon Frère le Paysan (To My Brother the Peasant), and again in 1900 for Grave’s Enseignement Bourgeois et Enseignement Libertaire (Bourgeois Education and Libertarian Education). He also provided work for a collective volume of lithographs in 1905 and later for Grave’s Patriotisme, Colonisation.

Despite his generous involvement, Cross remained ambivalent about creating overtly political images. He worried that propaganda risked narrowing the freedom of his artistic voice. At times he felt constrained by the utilitarian demands of such commissions, fearing that they reduced art to mere instrumentality. Nevertheless, he continued to donate paintings and drawings for fundraising lotteries supporting anarchist publications, striking a balance between his ideals and his devotion to pure artistic integrity.

Influence and Legacy

The resonance of Cross’s art extended far beyond his lifetime. In 1904, the young Henri Matisse met him in Saint-Tropez. The encounter was pivotal. Matisse was captivated by Cross’s bold use of non-local color, his willingness to distort natural forms for expressive effect, and the sheer vitality of his brushwork. These elements would become the foundation stones of Fauvism, the movement that catapulted Matisse and his circle into modernist prominence.

Other artists, too, felt Cross’s influence—André Derain, Wassily Kandinsky, and a host of others drew inspiration from the sensuous liberation of his palette and his daring in breaking from naturalism. Cross was both a bridge and a catalyst, helping shift the energy of painting from Neo-Impressionist science toward the expressive explosion of early 20th-century modernism.

Paul Signac once described him as “an impassive and consistent thinker, who is simultaneously a passionate and strange dreamer.” That paradox captures his essence: a man at once rigorously committed to his ideals and yet profoundly moved by beauty, joy, and the imaginative promise of color.

Unlike Signac, however, Cross did not leave behind children or heirs to safeguard his reputation. After his death, his works were scattered, and his name gradually receded from public memory. Yet his influence lived on—in the canvases of Matisse and the Fauves, in the roots of abstraction, and in the enduring radiance of his surviving paintings.

Final Years and Death

The last decade of Cross’s life was marked by suffering. He endured rheumatism, weakening eyesight, and finally the ravages of cancer. Despite illness, he continued to paint whenever strength allowed, finding in art both solace and joy. He died on May 16, 1910, in Saint-Clair, just four days before his fifty-fourth birthday. His close friend and fellow anarchist artist Théo van Rysselberghe honored him with a commemorative medallion for his tomb, a quiet tribute to a painter who had lived and worked with uncompromising integrity.

Though his earthly life was cut short, his legacy endures. Today, his works are housed in some of the world’s foremost institutions—the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Modern Art, and beyond. Each canvas still shimmers with light, carrying his utopian hope into new centuries.

Artistic Hallmarks

Movements: Neo-Impressionism, Pointillism, Divisionism

Mediums: Oil painting, watercolor, printmaking

Themes: Harmony, nature, utopia, light as a transformative force

Techniques: Mosaic-like brushstrokes, radiant contrasts, decorative and rhythmic compositions

Influence: Fauvism and modernism—particularly Matisse, Kandinsky, and Derain

Henri-Edmond Cross did not simply paint the Mediterranean coastlines and gardens before him. He painted possibilities—worlds suffused with light, joy, and human harmony. His art offers more than aesthetic delight; it whispers of freedom, of beauty as a communal language, and of the enduring hope that painting itself might help shape a more just and radiant future.

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.

Henri-Edmond Cross Crossword Puzzle

Click Image