Cezanne

Still Life with Apples on a Sideboard, 1906

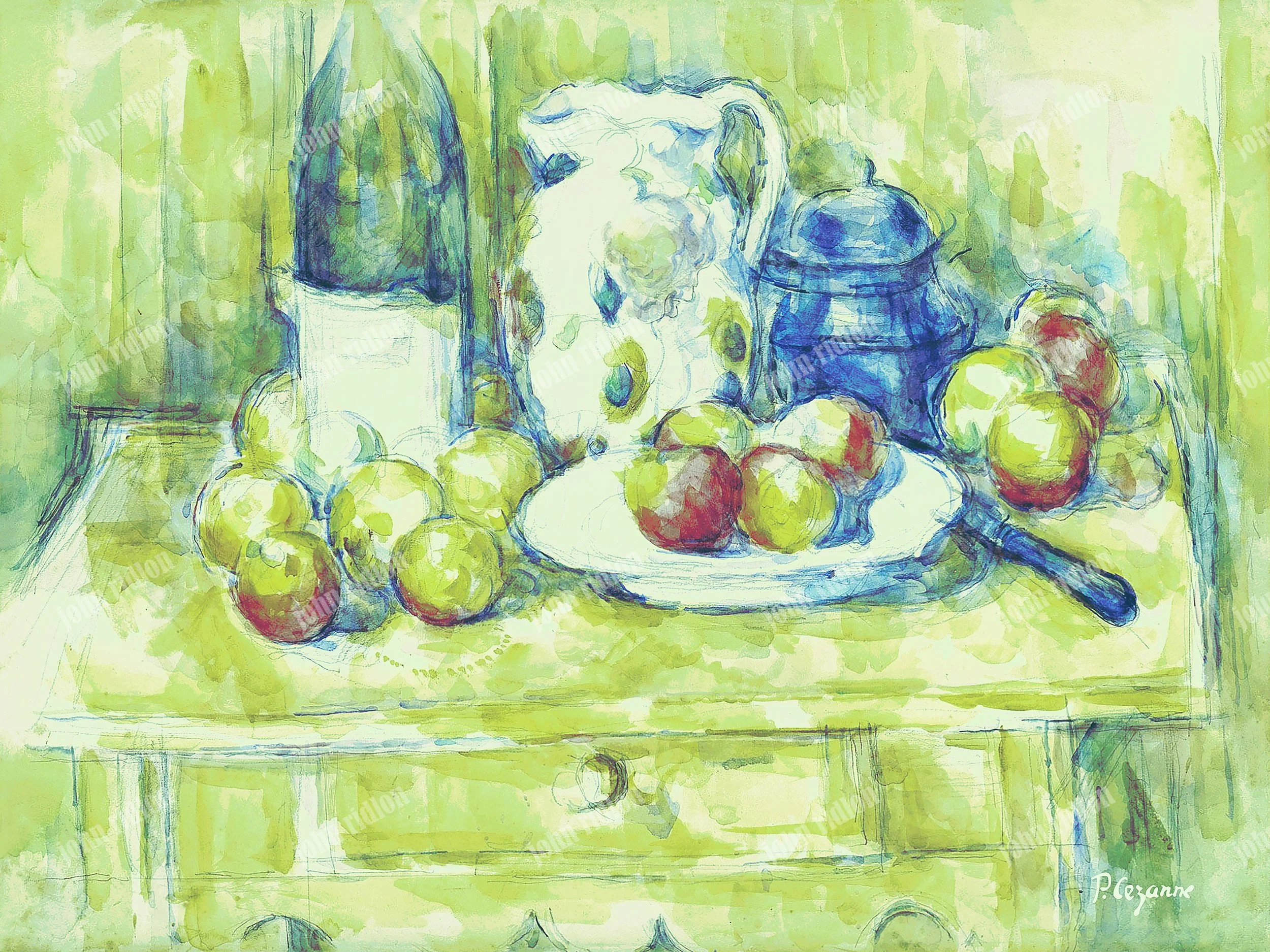

Still Life with Apples on a Sideboard, 1906-Version 2

In Still Life with Apples, Cézanne defies traditional perspective, using tilted tables and sculptural fruit to explore how objects occupy space. Across multiple versions, he transforms a simple arrangement into a study of perception, form, and the poetry of the everyday.

Still Life with Apples on a Sideboard, 1906 - Version 3

Still Life with Apples on a Sideboard, 1906 - Version 4

Abandoned House near Aix-en-Provence (1885)

In Abandoned House near Aix-en-Provence, Cézanne breaks from Impressionism, using geometry, layered brushwork, and color to reshape form and space, laying the groundwork for Cubism.

A Village Road near Auvers, 1873

During his 1872–73 stay in Auvers-sur-Oise, Cézanne worked alongside Camille Pissarro, adopting a brighter palette and focus on natural light. This period marked a key shift from his earlier dark tones toward the style that would define his Impressionist explorations.

Paul Cézanne's wife (1877)

Cézanne’s portrait of Hortense Fiquet emphasizes form, color, and composition over emotion, using her figure to explore structure and lay the groundwork for Cubism.

Seated Peasant (1892–1896)

Cézanne’s Seated Peasant (c. 1892–96) honors rural workers with structured brushwork and sculptural color. Though modest in size, the portrait conveys dignity and solidity, reflecting his Post-Impressionist vision.

Still Life with Bottle, Glass, and Lemons, 1868

Cézanne’s still lifes transform everyday objects into spheres, cylinders, and cones, emphasizing structure and spatial tension. Breaking from realism, they laid the foundation for Cubism and inspired modern artists like Picasso.

Vase of Flowers

Cézanne used still life to explore space and form, building objects from layered brushwork and subtle color shifts. By reducing everyday items to spheres, cylinders, and cones, he laid the groundwork for Cubism and modern art.

Dish of Apples, 1877

In Dish of Apples, Cézanne arranges fruit, cloth, and a screen with precision, using the napkin’s folds to evoke Mont Sainte-Victoire and connect still life to landscape.

In this Paris still life (1875–79), Cézanne transforms apples, cloth, and wallpaper through tilted perspectives and sculpted brushwork, turning the ordinary into a study of form that paved the way for modern art.

The Plate of Apples

At Jas de Bouffan, his family’s estate near Aix-en-Provence, Cézanne developed a new visual language rooted in geometry and structure. In this landscape, stark trees frame distant hills, revealing his move beyond Impressionism toward a more meditative and enduring vision of nature.

Trees and Houses Near the Jas de Bouffan (1885–1886)

The Fishermen (1875)

Curtain and Fruit (1898)

Three Pears

In Still Life with Floral Pitcher, Cézanne turns everyday objects—a family pitcher, fruit, and cloth—into studies of form, color, and light, creating meditative reflections on presence and perception.

In Three Pears, Cézanne transforms a modest subject into a study of balance, weight, and tonal harmony. Painted in oil, watercolor, and graphite, the motif reveals his pursuit of visual truth, turning simple fruit into a quietly dramatic meditation on form and space.

Marie Cézanne's Sister (1866–1867)

Paul Cézanne’s Portrait of Marie Cézanne, the Artist’s Sister (1866–67) offers a subtle, layered portrayal that invites varied emotional interpretations. Rather than expressing overt feeling, the painting suggests:

Picnic on a Riverbank (ca. 1873–74)

In Picnic on a Riverbank, Cézanne portrays three figures in a park setting, blending leisure with subtle social ambiguity. While echoing works by Tissot and Manet, his solid forms and structured planes of color mark a shift toward the geometric style that would shape modern art.

Four Bathers (Quatre baigneuses), 1877

Bathers (ca. 1874–1875)

In The Large Bathers, Cézanne reimagines the classical motif of nudes in nature by distorting anatomy and merging figures with their surroundings. The triangular composition recalls a Gothic cathedral, suggesting both harmony and tension between the sacred and earthly. Seen as the culmination of his bather theme, the work helped pave the way for Cubism and inspired artists like Matisse and Picasso.

Still Life with Apples and Peaches, 1905 01

This still life shows Cézanne’s devotion to everyday objects as a way to explore form, color, and space. A floral pitcher, fruit, and patterned cloth are rendered with shifting perspectives, luminous color, and subtle brushwork, turning the ordinary into a study of depth and presence.

Still Life with Apples and Peaches, 1905 02

Still Life with Apples and Peaches, 1905 03

Still Life with Apples and Peaches, 1905 04

Roses in a Bottle, 1904 01

In Roses in a Bottle (1900–1904), Cézanne turns a simple bouquet into a study of light, form, and color. Transparent washes and visible pencil lines give the flowers both delicacy and structure, while the angled background planes hint at the geometric vision that shaped early Cubism.

Roses in a Bottle, 1904 02

Roses in a Bottle, 1904 04

Rocks and branches (1895–1904) 01

In this view of the Bibémus quarry near Aix-en-Provence, Cézanne reduces rugged rock and twisting branches into interlocking planes of color and form. Painted between 1895 and 1904, the scene reflects his search for geometry in nature and foreshadows the birth of Cubism.

Rocks and branches (1895–1904) 02

Rocks and branches (1895–1904) 03

Rocks and branches (1895–1904)03

Endorsement Without Applause: Cézanne’s Collectors and the Language of Loyalty

Paul Cézanne’s path to recognition was neither straightforward nor immediate. Unlike many of his contemporaries, his reputation was not shaped by dazzling appearances at group exhibitions, nor by the approval of prominent critics. Instead, it grew quietly, nourished by the loyalty of fellow artists and a handful of discerning collectors who recognized the radical honesty of his vision. His story is less about applause than about persistence—about a painter whose solitude was balanced by a small circle of believers who helped carry his reputation into the future.

The Waning of Zola and the Faith of Artists

In the earliest stages of his career, Cézanne could count Émile Zola—his childhood friend—as one of his most ardent advocates. Zola once championed him as an untamed genius, a painter who might shake the foundations of French art. But by the 1870s, that enthusiasm began to falter. Zola grew increasingly impatient with Cézanne’s slow progress, writing in 1880 that he had “the temperament of a great painter who still struggles with problems of technique.” The words stung, even if Cézanne never openly protested them. Ever loyal, he continued to esteem Zola as a friend, even asking him on occasion to intervene on behalf of fellow Impressionists when they sought public recognition.

But the truest champions of Cézanne’s art were not men of letters—they were painters themselves. Degas, Renoir, Monet, Caillebotte, and especially Pissarro understood that Cézanne’s pursuit of sensation—his attempt to render not just the appearance of things but the experience of seeing them—was not weakness but revolution. Their support was quiet, often wordless, expressed less in manifestos than in the simple act of acquisition. To buy Cézanne’s paintings, to live with them in their studios and homes, was to affirm his value even when the public failed to.

Monet’s Loyalty: A Collector’s Testament

Among Cézanne’s peers, Claude Monet offered perhaps the most powerful endorsement. He invited Cézanne to Argenteuil in the early 1870s and visited him in Aix a decade later, cementing a friendship that was grounded in shared respect. Unlike many artists who exchanged gifts, Cézanne never offered Monet one of his canvases; yet Monet purchased them anyway. His collection eventually grew to fourteen paintings and a watercolor—more than he owned of any other artist.

This was no casual collecting habit. Monet’s acquisitions were acts of faith, each one a silent acknowledgment that Cézanne’s art mattered, not just to posterity but to his own artistic evolution. That level of commitment—private, consistent, unshowy—illustrates the quiet language of loyalty that surrounded Cézanne.

Gauguin’s Tribute: Reverence and Misinterpretation

Through Pissarro, Cézanne came into contact with Paul Gauguin, then a stockbroker with an emerging passion for art. Between 1877 and 1883, Gauguin acquired at least six of Cézanne’s works. Among them, Still Life with Fruit Dish became a touchstone. Gauguin guarded it with fervor, vowing to part with it only in dire necessity. He displayed it prominently in his studio, showing younger artists how Cézanne’s brush seemed to construct form and space through vibration and color rather than line.

Yet Gauguin’s understanding of Cézanne’s method was partial at best. He admired the surface effects, but his own attempts to replicate Cézanne’s “sensation” often fell short, flattening into decorative pattern rather than spatial depth. In his writings, he called Cézanne “polychromatic, even polyphonic”—an evocative phrase but one that revealed more admiration than comprehension. Like so many of Cézanne’s admirers, Gauguin’s tribute was not an intellectual analysis but a possession, a conviction that owning Cézanne’s work was itself an act of reverence.

The Solitude of Influence

Despite his circle of supporters, Cézanne himself was not a collector of art. He rarely acquired or displayed works by his peers, even when they gifted them to him. His generosity flowed outward—he gave paintings to friends like Zola or Cabaner—but seldom reciprocated through collecting.

In the shared company of painters such as Pissarro, Renoir, or Gauguin, it was often their styles that bent toward his, not the reverse. Cézanne absorbed the lessons of Impressionism, but he always redirected them toward his own ends, away from fleeting effects and toward enduring structure. Influence radiated outward from him, confirming the peculiar solitude of his genius.

Homage Across Generations

By the dawn of the twentieth century, Cézanne had become less a misunderstood eccentric than a figure of continuity between generations. His work bridged the Impressionists and the Symbolists, and even pointed toward the abstraction to come.

In 1901, the Nabi painter Maurice Denis unveiled Homage to Cézanne, a monumental tableau that placed Still Life with Fruit Dish at its center. The painting gathered around it a circle of admirers—Redon, Vollard, Denis himself—paying collective tribute to a master they recognized as foundational. Denis later confessed that as late as 1890, Cézanne had seemed almost mythical, so rarely was he seen in public. Yet now his presence was felt everywhere.

The tribute did not end there. Writers, too, began to take note. In 1905, Charles Morice circulated a questionnaire to fifty-seven artists asking, “How do you feel about Cézanne?” Many who responded already owned his work. Their answers placed Cézanne at the heart of the modern conversation, elevating him from marginality to centrality.

A Legacy Beyond Applause

Cézanne’s legacy was not secured by critics’ praise or the roar of exhibitions. It was built on quieter gestures: the steady acquisitions of Monet, the reverent guarding of Gauguin, the homages of Denis, the unwavering respect of Pissarro. Each act of loyalty spoke louder than words, sustaining his reputation until the wider world could catch up.

Today, when we look at Cézanne’s still lifes, bathers, and mountain landscapes, we see not only the solitary labor of one man but also the constellation of friendships and convictions that carried his art into the future. These are the moments of recognition and reverence that Masterwork Prints seeks to preserve: living testaments to artists whose work transcends their time.

Between the Bathers and Us: Cézanne’s Energeia of Renewal

In the early twentieth century, Paul Cézanne became a touchstone not only for his paintings but for the ideas he shared with younger artists who sought him out in Aix-en-Provence. Visitors such as Émile Bernard and Maurice Denis recorded fragments of their conversations with him at Les Lauves—reflections on art, nature, and perception that continue to resonate today. These recollections, though scattered, reveal a vision not grounded in theoretical systems but in the lived intensity of sensation.

For Cézanne, painting was inseparable from perception itself. His way of seeing was profoundly personal, a mode of grasping the world that could never be codified or imitated. Denis captured this truth in 1907 when he observed that Cézanne’s work was so inseparably bound to his inner being that “only Cézanne could make a Cézanne.” His brushwork did not merely describe appearances—it revealed them. His forms did not simply represent—they vibrated with resonance, carrying the presence of lived experience into paint.

Energeia and the Living Pulse of the Bathers

Nowhere is this vitality more evident than in Cézanne’s Bathers. These enigmatic figures seem to contain more than muscle or bone. Their bodies stretch, bend, and merge with the world around them, as if shaped by a current of energy that also ripples through trees, rivers, skies, and earth. The entire scene becomes animated by a hidden rhythm, binding figure and landscape into one continuous force.

Aristotle called this energeia: the living essence that grants beings the power to act, move, and think. The concept feels profoundly relevant to Cézanne’s art. His paintings embody movement and thought at once, collapsing the distance between perception and being. A genuine thought, he seems to remind us, must move—must stir something—if it is to be felt at all.

Cézanne’s bathers radiate this vitality with a curious serenity. They are untouched by aggression, guilt, or fear. Instead, they exude quiet joy, as though immersed in a state of elemental renewal. Across cultures, water has long symbolized life, cleansing, and rebirth. In Cézanne’s hands, the motif of the bather becomes more than a pastoral scene: it is a meditation on regeneration, both bodily and spiritual.

The Quiet Gift of Renewal

What Cézanne offers us in these works is not spectacle but renewal. True pleasure, he suggests, carries restorative power. The joy of his bathers—unforced, unguarded, unaggressive—expands our capacity for empathy. It is a pleasure akin to deep rest, one that cleanses, clarifies, and prepares us to meet life with renewed strength.

What struck me most, on closer study, was their freedom from suffering. These figures do not display anxiety or anger; they bear no trace of invisible burdens. Instead, they embody a rare humanity: one content simply to exist, to share presence, to be alive together. In a world often marked by conflict or sorrow, Cézanne imagines a vision of community unclouded by arbitrary pain.

This is his quiet gift. His bathers remind us of the pleasure of renewal—pleasure that restores clarity, strengthens empathy, and reawakens the pulse of life. They remind us of what it feels to emerge refreshed, as if stepping from water, ready once more to live.

The Ten Most Famous Paintings

1. The Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses) – A monumental work blending landscape and nude figures, often seen as a precursor to Cubism.

2. The Basket of Apples – A still life masterpiece known for its tilted perspective and geometric tension.

3. Mont Sainte-Victoire – A recurring subject in Cézanne’s work, this mountain became a symbol of his evolving style and spatial experimentation.

4. The Card Players – A quiet, meditative scene of peasants playing cards, celebrated for its composition and psychological depth.

5. Boy in a Red Vest – A portrait that showcases Cézanne’s mastery of color modulation and form.

6. Curtain, Jug and Fruit Bowl – A still life that plays with balance, texture, and spatial ambiguity.

7. Apples and Oranges – Another iconic still life, rich in color and rhythm, emphasizing Cézanne’s love for everyday objects.

8. Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Chair – A portrait of his wife, marked by introspection and subtle emotional tension.

9. The House with the Cracked Walls – A landscape that reveals Cézanne’s architectural approach to nature.

10. A Modern Olympia – A provocative reinterpretation of Manet’s Olympia, blending satire and sensuality.

The Biography of Paul Cezanne

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.