Pablo Picasso

Cubism

When Pablo Picasso passed away in April 1973 at the age of 91, he had become one of the most celebrated and influential artists of the twentieth century. His career stretched across nearly the entire century, and he played a key role in many of its most important artistic movements. Picasso created an extraordinary range of work—paintings, sculptures, drawings, etchings, constructions, and ceramics—moving effortlessly between mediums and styles. His natural talent and versatility seemed limitless.

Picasso was also a master of self-promotion, which helped redefine how the public viewed artists. No longer seen simply as instinctive geniuses, artists like Picasso began to be understood as deliberate creators of their own image and persona. Art historian Sam Hunter once wrote, “Picasso, the man and the artist, has cast a spell on his age.” Many critics and writers have likened him to a magician—someone who could transform anything he touched and reinvent himself again and again. This ever-changing, elusive quality is part of what keeps Picasso so fascinating. His life and work continue to inspire scholarly debate and draw crowds to exhibitions, including those featured at Masterwork Prints.

While some believe an artist’s life isn’t essential to understanding their work, Picasso’s art is deeply personal. He once said, “The way I paint is my way of keeping a diary,” showing how closely his art was tied to his experiences. His long life included many homes and cities, several romantic relationships and children, and friendships with other artists, poets, and writers. His paintings often reflected his surroundings, his changing domestic life, and his evolving sense of self. Each new style he adopted was rooted in his own life, making him one of the most relatable and human of artists. He was always drawn to the familiar—the people, places, and emotions he knew best.

Picasso was born on October 25, 1881, in Málaga, southern Spain, with the full name Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Crispín Crispiniano Santísima Trinidad. He was named Pablo Ruiz Picasso after his parents, José Ruiz Blasco and María Picasso López, but later dropped his father’s surname and became simply Pablo Picasso. His father was a painter and art teacher, and Picasso began drawing at a young age. In 1891, the family moved to La Coruña, where Picasso enrolled in the School of Fine and Applied Arts, where his father taught. By age 13, he was already producing oil paintings, including portraits of his family. In 1895, he began exhibiting and selling his work modestly. That same year, the family moved again—this time to Barcelona—where Picasso entered the Art School.

Barcelona became a vital center for Picasso’s early development. There, he formed close friendships with artists like Manuel Pallarès, Carlos Casagemas, and Jaime Sabartés (who would later become his trusted secretary). Around 1900, Picasso began mingling with the artists and writers of Els Quatre Gats, a bohemian tavern that served as a hub for avant-garde Catalan creatives inspired by Paris. Though he had been painting large religious works like First Communion and Science and Charity (1896), he soon shifted toward more experimental work—creating drawings for Catalan journals, designing posters, and painting portraits of his new circle. His first solo exhibition took place at Els Quatre Gats in 1900.

Paris was the ultimate destination for these young artists, and in October 1900, Picasso traveled there with Casagemas. They rented a studio, visited the Louvre, and Picasso signed a contract with Catalan dealer Pere Mañach to represent him in Paris. However, Casagemas’s romantic troubles with his model Germaine led to heartbreak, and the two returned to Barcelona. In early 1901, Picasso learned that Casagemas had taken his own life in Paris. That May, Picasso returned to Paris, moved into the sculptor Manolo’s studio, and later created several haunting works in memory of his friend.

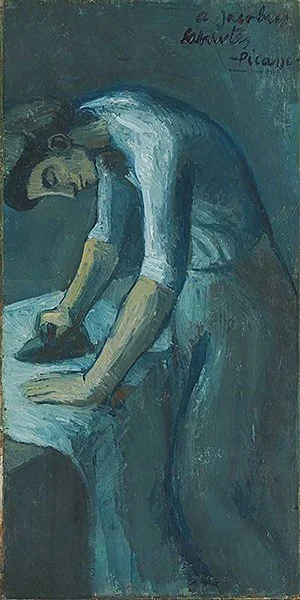

Picasso didn’t settle permanently in Paris until 1904. The years before were difficult—he had no fixed studio and little recognition. Back in Barcelona in 1903, he painted his Blue Period works, which reflected his struggles and depicted the poor, the elderly, and the blind. His large canvas La Vie captured the uncertainty and tension of the artist’s path. Once in Paris, his palette began to brighten, and he entered his Rose Period, painting traveling acrobats and circus performers. He became close with poets Max Jacob, Guillaume Apollinaire, and André Salmon, and together they formed the “bande à Picasso,” gathering at the Le Lapin Agile café. He lived and worked in the Bateau-Lavoir, a rundown artists’ studio in Montmartre, and began a relationship with Fernande Olivier, who moved into his studio in 1905.

During this time, Picasso was highly receptive to new artistic influences. The Fauvist works of Matisse at the 1905 Salon d’Automne, along with retrospectives of Ingres, Gauguin, and Cézanne, had a profound impact on him. Inspired by these avant-garde developments, Picasso began forging his own revolutionary style. A trip to Gósol, a village in the Spanish Pyrenees, marked a turning point. His art became more simplified and monumental, focusing on the human figure in a sculptural way. One of the most striking examples of this new approach was his 1906 portrait of Gertrude Stein, his new patron.

Dora Maar helped Picasso secure a studio on the rue des Grands Augustins in Paris, where he would go on to paint Guernica—a monumental work that she recognized as historically significant. She photographed its creation, preserving its evolution for future generations.

In 1907, as Matisse unveiled his Blue Nude, Picasso responded with a groundbreaking piece that would become central to his legacy: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. This painting marked a turning point, as Picasso began to incorporate African art influences, blending them with the structural insights of Cézanne and the inspiration drawn from his growing friendship with Georges Braque. These elements shaped his artistic direction for years to come.

Picasso’s work soon caught the eye of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, a young and affluent art dealer. Kahnweiler began purchasing Picasso’s pieces and eventually offered him an exclusive contract, providing financial stability. By 1909, Picasso had moved into a new studio on Boulevard de Clichy, and in 1912, he relocated again—this time to Montparnasse, a vibrant hub for artists.

During this period, Picasso and Braque became close collaborators. From 1910 to 1912, they worked side by side, vacationed together, and developed a shared visual language. Their paintings—still lifes, café scenes, musical instruments, and portraits—were rendered in muted tones and fragmented forms, sparking a revolution in how art could represent reality. In 1912, they began incorporating materials like faux wood grain and pasted papers into their compositions, challenging traditional notions of fine art and its reliance on precious materials.

By early 1913, Picasso’s first major retrospective in Munich marked his growing international reputation. His work was being promoted by critics like Apollinaire and Salmon, and he was beginning to enjoy financial success. However, the outbreak of World War I disrupted this momentum. Friends and collaborators were scattered—Apollinaire and Braque were sent to the front, and Kahnweiler, being German, fled to Switzerland.

During the war years, Picasso split his time between Paris and Barcelona and entered a new social circle that included dealer Léonce Rosenberg, poet Jean Cocteau, composer Igor Stravinsky, and choreographer Sergei Diaghilev. These connections led to new creative ventures. In 1917, Picasso collaborated with the Ballets Russes on the ballet Parade. While visiting Italy, he met Russian dancer Olga Kokhlova, whom he married in 1918. That same year, he moved into a refined apartment and studio on rue La Boëtie, reflecting his elevated social status.

Picasso’s artistic output during this time was diverse. He continued exploring Cubism while also embracing a neo-Classical style influenced by Ingres. His subjects included monumental female figures, Mediterranean landscapes, and scenes of motherhood. In 1921, Olga gave birth to their son, Paulo.

In the early 1920s, Paris was buzzing with Dada and Surrealism. Though Picasso didn’t formally join these movements, he was revered by their leaders—especially André Breton, who admired Picasso deeply and helped sell Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1924. In 1925, Picasso’s painting Three Dancers marked another stylistic shift, echoing the emotional intensity and dreamlike qualities of Surrealist art.

This period saw Picasso pushing the boundaries of form. His depictions of the human figure became increasingly distorted, sometimes violently so. He once described his painting as a “sum of destructions.” In 1926, he created a striking piece shaped like a guitar, made from torn cloth and protruding nails. Toward the end of the decade, his portrayals of Olga grew darker—she appeared as a screaming, monstrous figure, reflecting the tension in their marriage.

In 1927, Picasso began a relationship with Marie-Thérèse Walter, a 17-year-old schoolgirl. Her soft, rounded features soon dominated his art, appearing in sensual and dreamlike forms. Around this time, Picasso returned to sculpture, a medium he hadn’t explored since his early Cubist constructions. He learned to weld metal in Julio González’s studio, creating large rod-like sculptures and numerous preparatory drawings.

In 1931, Picasso began working in a spacious sculpture studio in a converted stable at his château in Boisgeloup, which he had purchased the year before. There, he sculpted a series of large busts of Marie-Thérèse, their swollen and bulbous forms echoing his painted depictions of her. During summers in Juan-les-Pins, he also began incorporating real objects into his sculptures—assembling and casting them into surreal hybrids. This technique would become a hallmark of his sculptural work in the years ahead.

Picasso’s relentless innovation and emotional depth continue to inspire artists and collectors alike. His legacy lives on through exhibitions, scholarship, and platforms like Masterwork Prints, where the echoes of his genius still resonate.

By the early 1930s, Picasso had firmly established himself as a major figure in the international art world. His work was featured in prominent exhibitions across Paris, London, and New York, and in 1932, Christian Zervos—editor of the influential Parisian journal Cahiers d’Art—published the first volume of a catalogue raisonné, aiming to document Picasso’s entire body of work. In response to this growing recognition, Picasso began dating his drawings and paintings more consistently. He also produced around 100 etchings during the 1930s for dealer and publisher Ambroise Vollard, adding to his already vast output.

Earlier in his career, Picasso had used the Harlequin figure as a kind of alter ego, a way to explore layered color and identity. But in the 1930s, the Minotaur took center stage. A recurring symbol in his work, the Minotaur allowed Picasso to reimagine the Spanish bull as a complex figure—embodying forbidden desire, grotesque physicality, and human vulnerability. Sometimes depicted as a blind beast needing guidance, the Minotaur became a metaphor for inner turmoil and fragility.

Picasso returned to Spain in 1933 and 1934, though these would be his final visits. When civil war erupted in 1936, he supported the Republican cause and was named honorary director of the Prado Museum in Madrid. His circle expanded to include Surrealist poet Paul Éluard, photographer Man Ray, and Dora Maar, who became both his lover and artistic collaborator. His personal life was complicated—still married to Olga but living separately, while also supporting Marie-Thérèse Walter, who had given birth to their daughter Maya in 1935.

In 1937, Picasso created Guernica, his most overtly political painting. Though he had long been interested in social issues, Guernica marked a dramatic shift—a monumental condemnation of war and violence, inspired by the bombing of the Basque town during the Spanish Civil War. The painting was immediately recognized as a masterpiece and toured England the following year. Other works from this period, like the Weeping Woman series, echoed the emotional devastation of war while also portraying Dora Maar in her distinctive, theatrical attire.

During World War II, Picasso remained in Paris under the Nazi Occupation. His work from this time reflected the tension and scarcity of the era—still lifes of food, skulls, and candles, as well as distorted portraits of Olga, twisted into grimaces and contorted poses. These introspective themes were shaped by both the oppressive Vichy regime and the isolation of wartime life. Picasso’s decision to stay in Paris made him a symbol of resilience and liberation when the war ended. In 1944, he joined the French Communist Party, and his Dove lithograph (1949) was chosen as the emblem for the World Peace Congress.

Throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, Picasso continued to explore political themes in works like The Charnel House (1945), Massacre in Korea (1951), and the War and Peace murals (1952). He also created a famous portrait of Stalin in 1953, further cementing his role as a cultural figurehead for the Communist movement. At the same time, he deepened his connection to southern France, painting Mediterranean scenes at the Château Grimaldi in Antibes and beginning a prolific period of ceramic work at the Madoura pottery in Vallauris.

Despite his public persona, Picasso’s art remained deeply personal. During the war, he met Françoise Gilot, a painter who would become his partner and the mother of his children Claude (born 1947) and Paloma (born 1949). Their relationship was passionate but turbulent, and by 1951, Picasso was also involved with Geneviève Laporte. He divided his time between Paris, Saint-Tropez, and Vallauris, where he rented the villa La Galloise. After Françoise left him in 1953, Picasso created the Verve Suite—a series of 180 drawings featuring circus performers, clowns, Cupids, and aging artists studying young models. These works reflected a period of introspection and marked the emergence of the painter-and-model theme that would dominate his late career.

By 1955, Picasso had settled permanently in the south of France, returning to Paris only once before his death. He lived and worked in a series of villas and châteaux, producing an astonishing variety of work—from wooden sculptures to a mural for the UNESCO building in Paris. He also began revisiting the great masters, creating large series inspired by Delacroix’s Femmes d’Alger, Velázquez’s Las Meninas, and Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’Herbe. These homages reflected his awareness of his own stature and legacy.

Rather than looking outward, Picasso turned inward. His late works focused on studio interiors at La Californie in Cannes and Notre-Dame-de-Vie in Mougins, his final studio. He painted intimate portraits of Jacqueline Roque, whom he met in the late 1940s and married in 1961. He also created the Suite 347 etchings, reflecting on his own life and artistic journey.

In his final years, Picasso’s work expressed a powerful duality: a fierce, Spanish intensity—exploring violence, death, and fear—balanced by a joyful, sensual vitality. Some of his last self-portraits are haunting, skeletal, and filled with dread. Yet others burst with erotic energy and exuberant brushwork. If Picasso faced death with anguish, it was only because he had lived with such passion and intensity.

His legacy continues to resonate, not only in museums and scholarship but also through platforms like Masterwork Prints, where the emotional depth and creative daring of his work remain as compelling as ever.

Picasso and a Bull Mask, 1970

Guernica, 1937

Jacqueline Roque, 1961

Le Bal Tabarin, 1903

Jeune Fille Endormie, 1935

Abstraction Background with Blue Cloudy Sky, 1930

"Family of Saltimbanques" (1905)

Woman Ironing, 1904