Degas

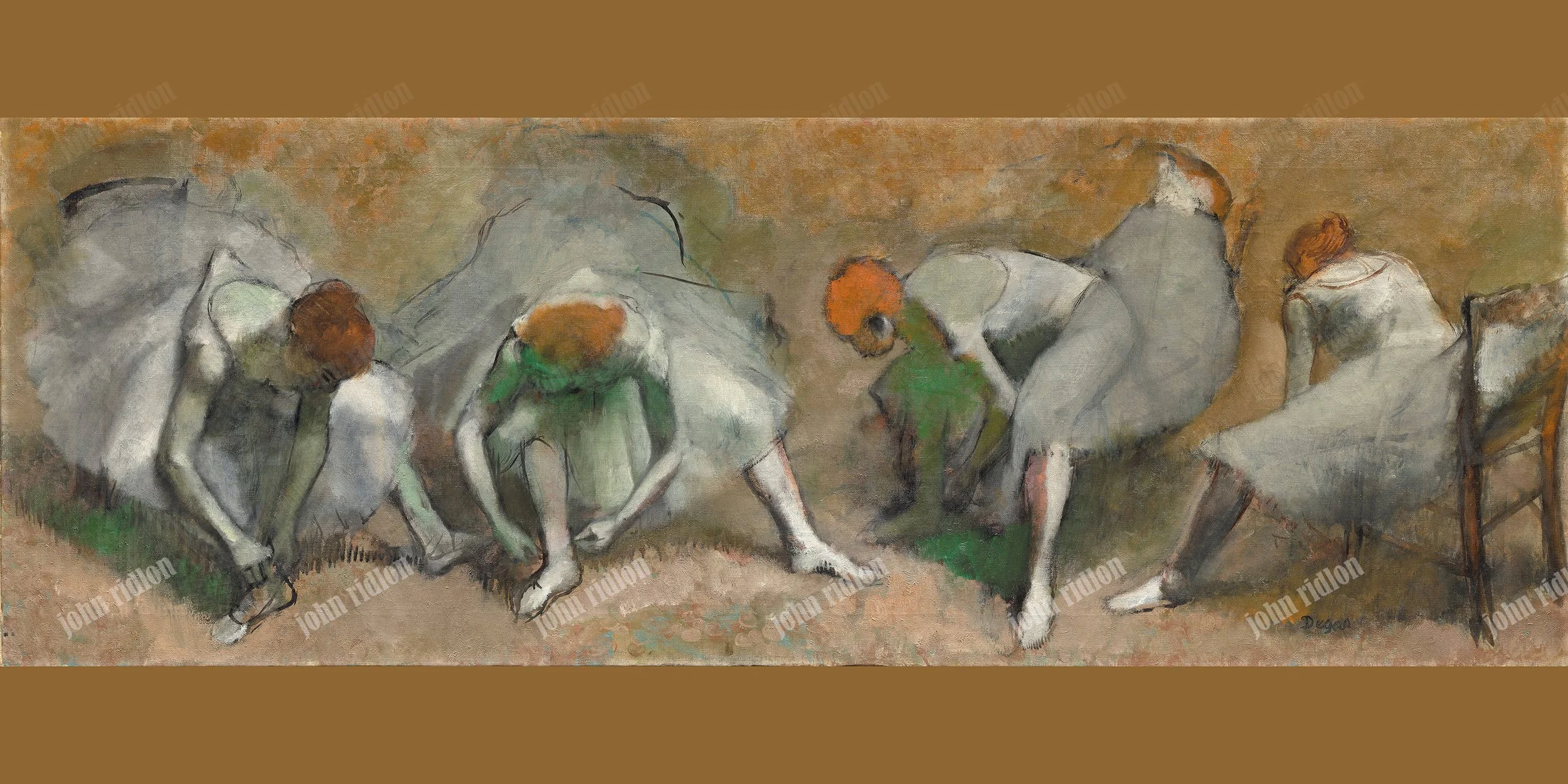

Edgar Degas: Frieze of Dancers, 1895 Initial Version

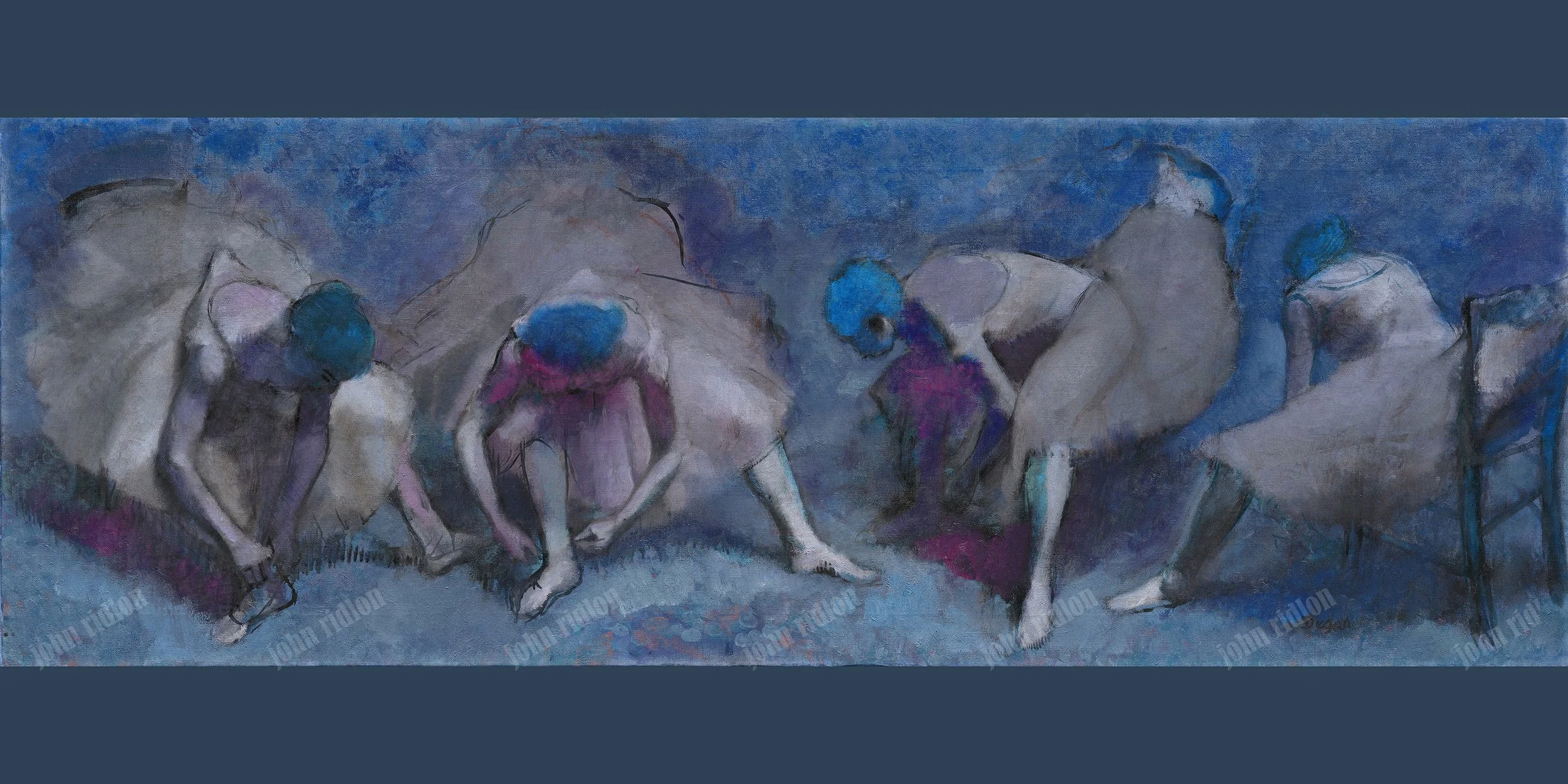

Edgar Degas: Frieze of Dancers, 1895 - Version 2

Edgar Degas: Frieze of Dancers, 1895 - Version 3

Edgar Degas: Frieze of Dancers, 1895 - Version 4

The Dance Class, 1874 1

The Dance Class, 1874 2

The Dance Class, 1874 3

The Dance Class, 1874 4

The Ballet Class

The Dancing Class by Edgar Degas, 1870 Initial Version

The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage, 1874 - Initial Version

Dancers, Pink and Green, 1890 - Initial Version

Two Dancers, 1895 - Initial Version

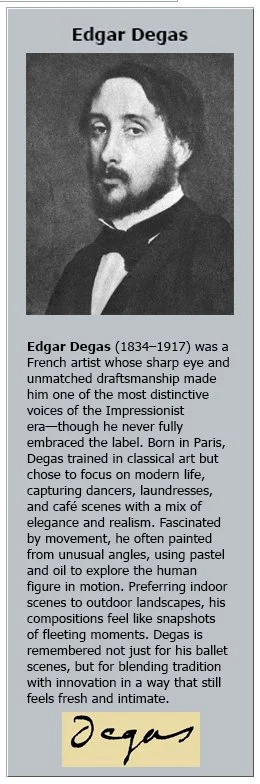

The Biography of Edgar Degas

Edgar Degas: A Modern Master in Motion

During his lifetime, Edgar Degas was already hailed as a visionary of modern art. Since his passing in 1917, his stature has only grown. His work continues to resonate—vivid, incisive, and unmistakably original. Degas didn’t merely witness the world; he dissected it, exposing its rhythms, tensions, and quiet revelations with razor-sharp visual intelligence and wit.

He lived through an era of sweeping change. Industrialization reshaped France, and Paris—his birthplace and lifelong home—underwent a dramatic transformation. The city that emerged during the Second Empire and early Third Republic became Degas’ stage: a metropolis of motion and spectacle, inhabited by dancers, jockeys, café patrons, and laborers. Though born into a privileged banking family, Degas chronicled the rituals of the haute bourgeoisie while also turning his gaze toward the working class. His art captured both refinement and grit, revealing a Paris alive with complexity and contradiction.

A Career in Three Movements

Degas’ artistic evolution unfolded in three distinct chapters:

• 1855–1865: The Aspiring Historian

In his formative years, Degas aspired to join the ranks of academic history painters. He immersed himself in the study of old masters, revering their techniques and ideals as he honed his craft.

• 1865–1885: The Realist and Impressionist Ally

This middle phase marked a decisive shift toward Realism and a close, though ambivalent, association with the Impressionist movement. While Degas resisted the label, he shared their fascination with modern life—its fleeting gestures and candid moments. His work from this period is rooted in observation, yet infused with psychological depth.

• 1885 Onward: The Aesthetic Explorer

In his later years, Degas became increasingly absorbed by form, movement, and the expressive potential of the human figure. Ballet dancers, bathers, and women at work dominated his compositions. He ventured into new techniques—pastel, monotype, and daring arrangements—blending classical reverence with a restless modernity that made his style unmistakably his own.

Degas embodied contradiction: a traditionalist who reshaped modern art. He revered the past but refused to be confined by it. His legacy is one of tension and transformation—a reflection of his time and a tribute to the power of deep perception.

Degas lived wholly for his art. He never married, and his personal life remains largely obscured, known only through the quiet recollections of close companions. What is certain is his unwavering dedication to painting and his relentless pursuit of mastery.

Romanticism and Revolution

By the 1820s, the classical ideals that had long dominated French art began to fracture. A new movement—Romanticism—emerged, led by figures like Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix. Ironically, its roots lay in the innovations of Davidian-trained artists such as Baron Gros, who had already begun to infuse historical painting with emotion and drama.

Delacroix believed the classical tradition required renewal—something that reflected the turbulence of the age. France had endured revolution, war, restoration, and upheaval. To poet Charles Baudelaire, Delacroix’s vivid brushwork and bold compositions embodied the volatility of the era. His art was more than visual—it was psychological, political, and deeply personal.

The Rivalry: Ingres vs. Delacroix

By the 1840s, the French art world was sharply divided by the rivalry between Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Eugène Delacroix. Ingres, a master of line and clarity, drew inspiration from Raphael and Poussin. Delacroix, driven by color and movement, looked to Titian, Rubens, Rembrandt, and Michelangelo.

Their mutual disdain was legendary. When Delacroix was elected to the Academy, Ingres cast a vote against him. This feud became a defining artistic debate for a generation—including Degas, who absorbed both traditions while forging his own path.

Historical Drama and Artistic License

Amid this artistic tension, Paul Delaroche emerged as a pioneer of the genre historique—melodramatic historical scenes rendered with theatrical lighting and emotional intensity. His Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833) exemplifies the style: blindfolded, pale, and reaching for the block, Jane’s portrayal is more poetic fiction than historical fact. Yet it resonated deeply with audiences, blending sentiment and spectacle in a way that captivated the public imagination.

Italy: Classical Foundations and Personal Discovery

Though France had become the heart of the art world, Italy’s classical legacy still held profound influence. In 1856, Degas traveled to Naples, staying at his grandfather’s palazzo. There, he immersed himself in the Museo Nazionale Romano, studying ancient murals from Pompeii and masterpieces by Titian and Veronese. He read Dante, sketched the Sorrento coastline, and painted portraits of his family—most notably his troubled aunt, Laura Bellelli.

Rome: Art, Antiquity, and the Caldarrosti

While in Rome, Degas immersed himself in the city’s artistic and historical grandeur. He explored the Vatican’s treasures, studying Leonardo’s Saint Jerome, Canova’s Perseus, and the Papal collection of classical statuary. He meticulously copied Domenichino’s frescoes, examined mosaics attributed to Giotto, and sketched scenes from the Roman Forum and the Villa Borghese Gardens.

During this period, Degas became part of a vibrant circle of young artists known as the Caldarrosti—named after Rome’s roast chestnut vendors. Gathering at the famed Caffé Greco, they engaged in spirited discussions on art, music, and literature. Their conversations often revolved around cultural giants like Goethe, Byron, Shelley, Leopardi, Stendhal, and Berlioz, as well as the ongoing debate between Ingres and Delacroix.

Inspired by these exchanges, Degas began developing religious and mythological works, including studies for Saint John the Baptist and the Angel and paintings influenced by Dante. Yet self-doubt crept in, and many of these projects remained unfinished.

Naples, Florence, and the Bellelli Family

In August 1857, Degas made a brief return to Naples to continue copying murals from Pompeii. By mid-October, he was back in Rome, where he grew close to Gustave Moreau. Under Moreau’s mentorship, Degas deepened his appreciation for the expressive power found in the works of Delacroix, Rembrandt, and the Venetian masters.

After short visits to Arezzo, Assisi, and Perugia, Degas arrived in Florence in August 1858. He stayed with his aunt Laura Bellelli, whose quiet resilience and troubled marriage would later inspire The Bellelli Family—a painting that marked a turning point in Degas’ artistic evolution. It signaled a shift from classical studies to psychological insight, from tradition to modernity.

In Florence, Degas worked with renewed intensity. He studied the Florentine masters, read Pascal’s Pensées, and sketched mythological and historical subjects such as David and Goliath and Blind Oedipus. Yet beneath the discipline, a quiet melancholy stirred. “There is an emptiness that even art cannot fill,” he confided to Moreau—a poignant reflection of the emotional weight he carried. The death of his grandfather and the temporary absence of Laura Bellelli deepened this sense of loss.

When Laura returned, Degas concentrated on preparatory sketches for her portrait. With Moreau preparing to leave Italy and the Paris Salon approaching, Degas grew eager to return to France. He wrote to his father, requesting help in securing a studio where he could complete the painting.

The Bellelli Family: A Portrait of Distance

Widely regarded as Degas’ first true masterpiece, The Bellelli Family is a psychological group portrait of extraordinary depth. Laura Bellelli is depicted in mourning for her father, her poised and refined features echoing the influence of Ingres and Bronzino. Her daughters, Giulia and Giovanna, are rendered with subtle contrast—one formal and composed, the other relaxed and natural. Meanwhile, her husband Gennaro sits apart at his desk, absorbed in his work, physically and emotionally distant.

The composition is pyramidal in structure but fractured in feeling. The emotional divide between Laura and Gennaro is unmistakable. Degas produced numerous studies in pursuit of a visual language that could convey the tension, restraint, and quiet sorrow that permeated the household. This is not merely a portrait of individuals—it is a meditation on relationships, silence, and the weight of domestic life.

A Changing Art World: The Rise of Modernism

The 1860s ushered in a seismic shift in French art. With the deaths of Delaroche, Delacroix, and Ingres, an era rooted in classical and academic tradition came to a close. In its place, new movements—Realism, Naturalism, and a lingering Romanticism—began to challenge the old guard, reshaping the artistic landscape.

Growing dissatisfaction with the Academy’s rigid standards sparked public protests. In 1863, Napoleon III authorized the Salon des Refusés, a groundbreaking exhibition for artists rejected by the official Salon. Though Degas did not participate, the show featured works by Manet, Whistler, Fantin-Latour, Pissarro, and others. Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe drew fierce criticism, yet its boldness galvanized a younger generation of artists.

The Salon des Refusés weakened the Academy’s grip and opened the door to alternative venues. That same year, the École des Beaux-Arts underwent reform, appointing younger faculty and embracing more liberal teaching methods. As France prioritized industrial modernization, state support for the arts waned. Grand history commissions dwindled, and a new art economy emerged—one shaped by private galleries and public taste.

Changing Tastes: Realism and the Rise of Landscape

The economic boom of the Second Empire introduced a new class of art collectors with eclectic preferences. Realism gained traction, with artists like Courbet and Millet earning acclaim for their unvarnished portrayals of rural life and labor. Meanwhile, Fantin-Latour, Legros, and Whistler carried forward Delacroix’s legacy in quieter, more poetic forms.

Landscape painting also evolved. The Barbizon School—Daubigny, Rousseau, Troyon, Diaz de la Peña, and Corot—rejected idealized scenery in favor of direct observation. Working en plein air, they captured nature’s immediacy and atmosphere. Their approach profoundly influenced Degas and the emerging Impressionists, who embraced spontaneity and the fleeting qualities of light.

Painting Modern Life: Degas and the Pulse of Paris

By the late 1850s, a new artistic philosophy was taking hold: painting should reflect the present, not the distant past. Writers and critics began to champion art that captured contemporary life—its people, its streets, its moods. This cultural shift laid the foundation for movements that would redefine the very purpose of painting.

Émile Zola, a towering literary and critical figure, made his mark with gritty novels that exposed the realities of Parisian life. As an art critic, he urged artists to embrace personal expression and draw inspiration from the world around them. His belief in art as a mirror to society resonated deeply with Degas, who shared Zola’s commitment to truth and observation.

Baudelaire and the Spirit of Modernity

Among the voices shaping this new sensibility, none was more influential than Charles Baudelaire. A close friend of Manet and an ardent admirer of Delacroix, Baudelaire viewed Paris as a city of both enchantment and disillusionment. His poetry captured the paradoxes of modern life, while his essay The Painter of Modern Life became a manifesto for a new generation of artists.

Published in 1863, Baudelaire’s essay celebrated the work of Constantin Guys, a popular illustrator of Parisian street scenes. But it was more than praise—it was a provocation. Baudelaire called on artists to seek “that indefinable something we may be allowed to call modernity… the transient, the fleeting and the contingent.” He believed the artist’s role was to uncover the poetry of the everyday and find meaning in the moment.

Degas absorbed these ideas with intensity. Like Guys, he cultivated wit, curiosity, and a keen eye for detail. His portrayals of dancers, laundresses, and café-goers reflect Baudelaire’s vision of Paris—its elegance, its fatigue, and its quiet drama.

The Origins of Impressionism

Though Degas was closely aligned with the Impressionists, his approach often diverged in style and temperament. Impressionism emerged from debates about realism, perception, and the expressive power of the sketch. Romantic artists had already begun to value the oil sketch as a direct channel to artistic thought, and collectors responded with enthusiasm.

The term “Impressionist” was coined derisively by critic Louis Leroy in 1874, in response to Monet’s Impression, Sunrise. Yet the artists embraced it. Degas, along with Monet, Morisot, Pissarro, Renoir, Sisley, Cézanne, Guillaumin, and Caillebotte, exhibited together in eight independent shows between 1874 and 1886. Their work reflected a shared desire to depict contemporary life and break free from academic constraints.

Degas’ method was more structured than many of his peers. He focused less on light and atmosphere and more on form, movement, and psychological nuance. Still, his dedication to portraying modern life placed him firmly within the Impressionist fold.

A New Era for Art

The 1860s marked a definitive turning point in French art. With the passing of Delaroche, Delacroix, and Ingres, the classical tradition lost its dominance. In its place, naturalism, realism, and a late romanticism began to reshape the artistic conversation.

Public frustration with the Academy’s rigid standards led to reform and rebellion. The Salon des Refusés gave voice to the avant-garde, and although Degas did not exhibit there, the event catalyzed a broader transformation. Manet’s controversial Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe shocked critics but inspired a generation to seek new artistic paths.

As the École des Beaux-Arts modernized and state funding dwindled, artists turned to private galleries and independent networks. Degas, ever adaptive, found new ways to navigate this evolving art world—building a career that reflected both tradition and innovation.

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.

Degas Crossword Puzzle

Instructions

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.

PC instructions; left click in the word space you want. Then type with your keyboard.

Mobile instructions: touch the word space you want to fill in. Then touch the little black squares at the bottom of the screen. That will bring up your keyboard. Type in the word.

Click on Image