Edvard Munch

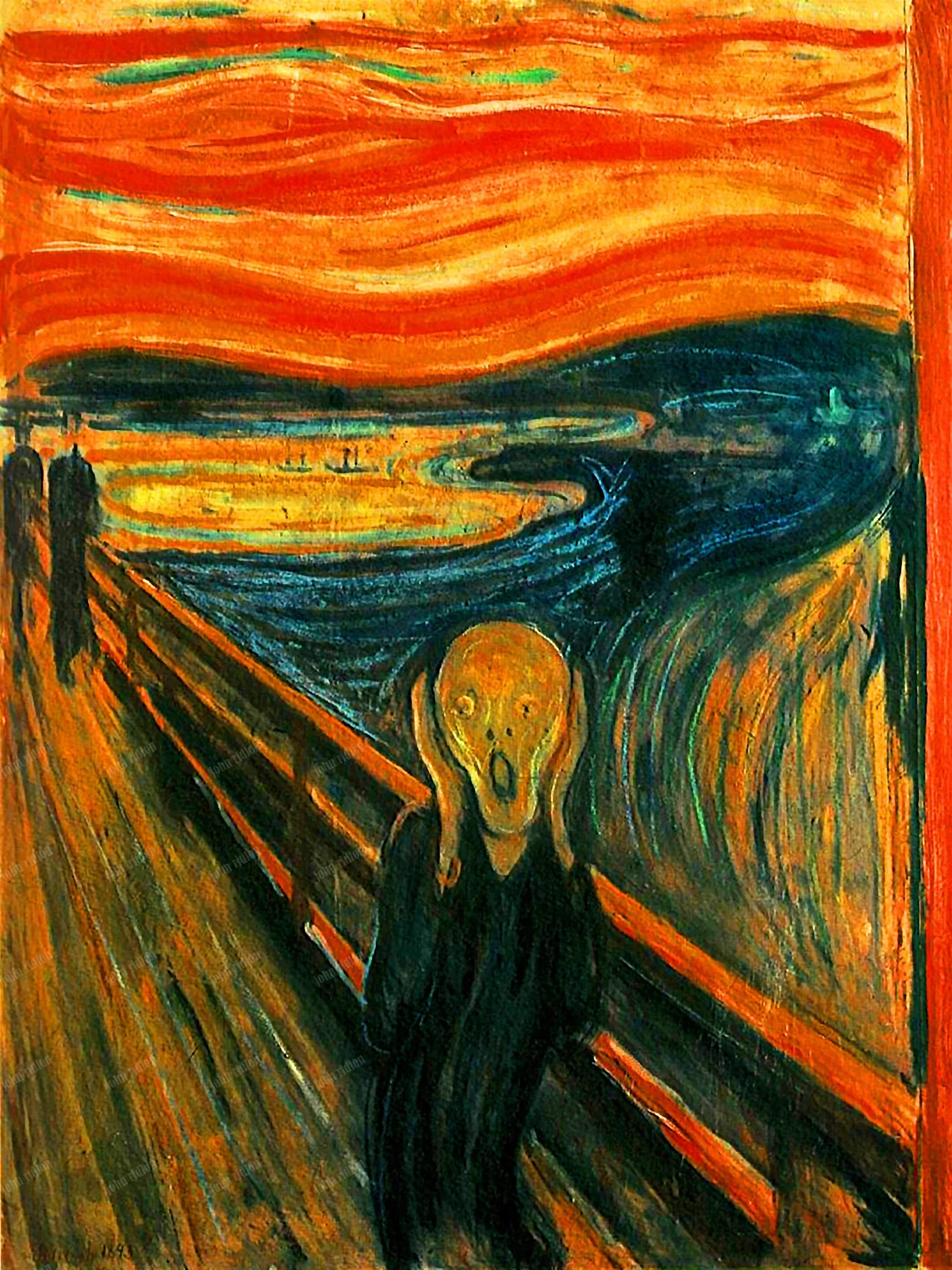

The Scream, 1910 - Initial Version

The Scream, 1910 - Version ll

The Scream, 1910 - Version lll

The Scream, 1910 - Version lV

The Biography of Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch: Painting the Soul’s Landscape

Edvard Munch, much like Gauguin and Van Gogh, turned away from the prevailing artistic traditions of his day—majestic landscapes, refined interiors, and the polished realism cherished by cultural elites. From the very start, Munch pursued a more profound goal: the creation of a visual language capable of conveying the raw, often unsettling truths of human feeling. “We want more than a mere photograph of nature,” he declared in 1888. “We want to create… an art that arrests and engages. An art created of one’s innermost heart.”

This conviction gave rise to his Frieze of Life, a cycle of paintings that chart the course of human existence—love, desire, jealousy, anxiety, and death. Shaped by both personal tragedy and philosophical reflection, the Frieze was not born as a single, unified project but gradually emerged as one. Each work was revisited, revised, and reimagined, as Munch sought to uncover what he described as its “soul.”

Symbolism and the Shoreline

Munch’s lyrical sensibility and his recurring imagery of solitary figures by the sea place him closer to the spirit of German Romanticism than to many of his contemporaries. He revered the moonlit meditations of Caspar David Friedrich and the visionary landscapes of Philipp Otto Runge. Like Wagner’s Ring cycle, the Frieze of Life was conceived as a Gesamtkunstwerk—a total artwork uniting emotion, symbolism, and atmosphere.

In 1918, Munch characterized the Frieze as “a number of decorative pictures… an image of life.” A sinuous shoreline runs through its panels, beyond which stretches the ceaseless ocean—an emblem of the unconscious, of eternity. Beneath the sheltering trees, life plays out in all its intensity, joy, and grief.

The Soul in Paint

Munch’s conviction that every painting possesses a metaphysical essence was deeply informed by his engagement with Nietzsche and Dostoevsky. Nietzsche’s assertion that behind every tangible phenomenon lies an eternal prototype resonated with Munch’s understanding of art as a spiritual endeavor. Dostoevsky’s probing of the human psyche—especially in The Idiot—fueled Munch’s own attempts to depict the mystical and the subconscious. He perceived each painting as a living entity: “I believe that each painting is an individual trying to achieve something of its own.” By continuously reworking his images, he believed he could bring forth more of their hidden truth.

A Life Rooted in Loss and Legacy

Munch’s early life in Kristiania (modern-day Oslo) was steeped in both religious devotion and intellectual tradition. In 1889, the sudden death of his father, a military physician, plunged him into a profound emotional crisis. His extended family included scholars, artists, and clergymen—among them the historian Peter Andreas Munch, whose grave Edvard later honored through both painting and print.

Introduced to drawing at the age of thirteen, Munch entered the National School of Art and Design in 1880. By eighteen, he was already exhibiting at the newly established National Gallery. His formative exposure to both classical and Romantic traditions laid the groundwork for an artistic career that would weave together personal anguish and universal human experience.

Edvard Munch: A City of Shadows

Late 19th-century Kristiania was a place of rigid morality and subdued despair. Until 1912, every citizen was legally required to be confirmed as Lutheran. The city offered no opera, no ballet—only music halls and taverns. Its central ritual was the daily promenade along Karl Johan Street, where the bourgeoisie displayed themselves in their finest dress. Munch captured this spectacle in Evening on Karl Johan Street (1892), presenting it not as celebration but as nightmare: ghostly, anxious figures confront the viewer directly, a motif he would intensify in Angst.

Industrialization transformed Kristiania at a brutal pace. The population, a modest 17,000 in 1801, swelled to more than 230,000 by 1900. Tuberculosis ravaged the working poor, leaving scars across families and neighborhoods. Munch knew its cruelty firsthand: his mother died of the disease when he was five, and his sister Sophie followed eight years later. Convinced that illness and death stalked him from birth, he wrote, “Disease and Insanity and Death were the black Angels that stood by my Cradle.” Haunted by this sense of inheritance, he resolved never to marry or raise children.

Sex, Disease, and Moral Hypocrisy

Munch’s anxieties were fueled not only by personal tragedy but also by the city’s conflicted approach to sexuality. Though prostitution was outlawed nationally in 1842, Kristiania permitted it under strict regulation. Women endured invasive medical inspections and constant police surveillance. Corruption was rife, and noncompliance could lead to imprisonment. The arrangement embodied a paradox: moral virtue publicly enforced while exploitation was quietly sanctioned.

This hypocrisy became a central theme in Norwegian culture. Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts (1881) laid bare the devastation caused by adultery, secrecy, and inherited syphilis. Munch admired the play deeply and later designed the set for a Berlin production in 1906—evidence of their shared indictment of society’s false pieties.

Art as Social Conscience

Munch’s earliest mentor, the realist painter Christian Krohg, was equally unafraid to confront such injustices. His novel Albertine and companion painting Albertine in the Waiting-Room of the Police Surgeon (1887) portrayed the humiliation endured by women trapped in prostitution. Executed with the scale and solemnity of history painting, the work shocked the public and contributed to legal reform.

These examples left a lasting imprint on Munch. His Inheritance (1898), together with its related print, addresses the transmission of syphilis with stark and unsparing imagery: women infected by unfaithful partners condemned to watch their infants suffer. Far from sensationalism, the work functions as an indictment—of gendered inequity, of the destruction visited upon the powerless, and of a society that condemned its victims while protecting its perpetrators.

In the late 19th century, Edvard Munch inhabited two contrasting worlds: the stifling moral rigidity of Kristiania and the freer, cosmopolitan atmosphere of Paris. In Norway, prostitution was tightly regulated and cloaked in stigma; in Paris, by contrast, social boundaries were more porous. Courtesans could reinvent themselves through marriage, while artists openly explored the lives of women on society’s margins. Writers such as Zola and Flaubert, along with painters like Manet, Degas, and Toulouse-Lautrec, transformed these figures into modern icons—symbols of desire, vulnerability, and defiance.

Munch’s early artistic trajectory unfolded against this backdrop. Though briefly pressured into engineering studies to satisfy his father, he soon entered the National School of Art and Design in 1881. Encouraged by his cousin Frits Thaulow—a landscape painter who had himself clashed with artistic conservatism—Munch secured a travel grant in 1885. Immersed in the radical currents of European art, he began to forge a style that would challenge prevailing norms.

The Sick Child and the Birth of Expressionism

Munch’s first teacher, the realist painter Christian Krohg, believed in art’s social responsibility. His Albertine in the Waiting-Room of the Police Surgeon (1887) laid bare the cruelty inflicted on women under Norway’s prostitution laws. Yet it was another of Krohg’s works, Sick Girl (1881), a harrowing vision of a child near death, that struck Munch most deeply.

In The Sick Child (1885–86), Munch returned to his own childhood trauma: the loss of his sister Sophie. With its coarse surface, muted colors, and turbulent brushwork, the painting departed radically from academic polish. Critics dismissed it as unfinished, but Munch defended its unvarnished honesty: “We can’t all paint fingernails and twigs.” He later described it as his first true “soul painting”—a work not meant to reproduce appearances but to embody emotion itself.

Life-Painting and the Bohemian Ideal

Munch’s philosophy of art was less indebted to German Symbolism or Strindberg, as has often been claimed, than to the radical bohemian circle led by Hans Jaeger. Jaeger’s anarchist worldview repudiated religion, marriage, and bourgeois respectability. His incendiary book From the Kristiania Bohemians, banned by the authorities, argued that celibacy, poverty, and sexual repression were society’s deepest ills. The group’s manifesto urged its followers to renounce family ties and even embrace suicide—a nihilistic doctrine that resonated with Munch’s own brooding sense of fate.

Reflecting on this period years later, Munch called it “Russian” in spirit—a time of trailblazing experiments carried out in what he described as a “Siberian town” locked in moral frost. “It was a testing time for many,” he told Pola Gauguin. “To describe it would require a Dostoevsky, or a mixture of Krohg, Jaeger, and possibly myself.”

Edvard Munch: Love, Loss, and the Making of the Frieze of Life

In the late 1880s, Edvard Munch entered his first serious love affair with Milly Thaulow, a married woman from a prominent Norwegian family. Their secret summers in Åsgårdstrand became the emotional and atmospheric backdrop for works such as Summer Night: The Voice. For Munch, the relationship embodied the irreconcilable tension between the religious piety of his upbringing and the bohemian ideals of free love and artistic freedom. This inner conflict became a wellspring for his creativity.

Although Munch never fully embraced Hans Jaeger’s radical creed—he rejected its call for suicide and the renunciation of family ties—Jaeger’s influence was undeniable. Munch began to paint with heightened emotional urgency, producing works like Hulda, an early precursor to his erotic Madonna, which he famously gave to Jaeger for his prison cell.

The Frieze of Life: Art from Inner Turmoil

The themes that would define Munch’s Frieze of Life—desire, jealousy, melancholy, and isolation—were born from the emotional turbulence of the Kristiania bohemian circle. Oda Lasson, the sole woman depicted in Munch’s painting Kristiania Bohemians, epitomized the group’s entangled passions. Her affairs with Jaeger, Krohg, and later Jappe Nilssen mirrored the dissolution of the group’s utopian ideals. Nilssen himself became a recurring figure in Munch’s art, his pensive form anchoring Melancholy III. In later years, Nilssen’s support as a critic helped legitimize Munch’s work in Norway.

Munch’s own romantic entanglements remained fraught. After Milly Thaulow, he withdrew into increasing solitude. His most destructive relationship was with Tulla Larsen, who pursued him across Europe. Their affair culminated in a violent quarrel in 1902, during which a pistol was fired, leaving Munch with a permanently injured hand—an injury immortalized in one of the earliest surviving X-rays.

Berlin: Scandal and Stardom

Munch’s fortunes shifted dramatically in 1892, when fellow Norwegian Adelsteen Normann invited him to exhibit in Berlin. His emotionally charged canvases—especially The Sick Child—clashed with the rigid taste of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s court. The exhibition was shut down within a week, prompting the Frankfurter Zeitung to sneer: “Art is endangered! An Impressionist, and a mad one at that, has broken into the herd of our fine solidly bourgeois artists.”

Yet the scandal proved a blessing. By December, the exhibition had reopened, and Munch’s work began traveling across Germany. In Berlin he became part of a lively circle of international bohemians who gathered at the Black Piglet tavern—among them August Strindberg, Stanisław Przybyszewski, Holger Drachmann, Jens Thiis, and Richard Dehmel. Their late-night debates spanned science, sexuality, alchemy, and Symbolist art.

Drachmann’s fascination with cabaret and the Parisian can-can inspired Munch’s print Tingletangle (1895), a playful nod to Berlin’s own dance craze. By then, Munch had secured his reputation—not only as a painter of emotion, but as a cultural force at the center of Europe’s avant-garde.

Women and the Frieze of Life

The tangled passions of the Kristiania Bohemians provided the raw material for Munch’s greatest artistic project: the Frieze of Life. Among the women who inspired its imagery was Dagny Juel, a free-spirited writer and pianist whose beauty and independence captivated his circle. Married to Przybyszewski, she bore him two children before her life ended tragically in Tbilisi in 1901, murdered by a jealous lover. While the press vilified her for her sexuality, Munch wrote a moving obituary in her defense.

Dagny, together with Milly Thaulow and Tulla Larsen, became the source of Munch’s symbolic depictions of women—figures that merged memory, desire, and myth. In Jealousy II, Przybyszewski appears pale and tormented beside a half-dressed Dagny, while Munch lingers in the background. These were not portraits in the traditional sense, but archetypes of emotion: embodiments of passion, betrayal, and longing that transformed private turmoil into universal image.

A Poem in Paint

By 1893, Edvard Munch began conceiving his work not as isolated images but as parts of a greater whole. His Berlin exhibition Study for a Series: Love, shown at Unter den Linden, gathered six compositions set against the pinewoods and shoreline of Åsgårdstrand—landscapes still haunted by memories of Milly Thaulow. The works—The Voice, Kiss, Vampire, Melancholy, Moonlight, The Scream, and Death in the Sick Room—formed a lyrical progression through love, loss, and existential dread.

Three years later, in 1896, ten canvases from the series appeared at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris, where they received wide attention. Munch continued to elaborate the cycle, producing a portfolio of prints under the title The Mirror, exhibited in Kristiania in 1897.

From the Modern Life of a Soul

The series reached its fullest expression in 1902, when Max Liebermann invited Munch to present the complete cycle at the Berlin Secession. Retitled From the Modern Life of a Soul, the installation was organized into four thematic sequences:

I. Seeds of Love – The Voice, Attraction, The Kiss, Madonna

II. Flowering and Passing of Love – Vampire, Melancholy, Jealousy

III. Life Anxiety – Evening on Karl Johan Street, The Scream

IV. Death – Death in the Sick Room, Dead Mother and Child

To bind the whole together, Munch added Metabolism—a spectral vision of a naked couple beneath a tree whose roots entwine human bones, a symbol of life emerging from death. “It may appear that the motif… stands somewhat apart,” he explained, “yet it is as necessary for the entire Frieze as a buckle is for a belt.”

A Vision Without a Home

Munch long hoped to sell the Frieze of Life as a single, unified installation, ideally housed in a dedicated room that would preserve its emotional and architectural coherence. “Each individual panel,” he wrote, “should be shown to its total advantage without the overall impression being compromised.” But no patron came forward.

The cycle continued to travel—Leipzig (1903), Kristiania (1904), Prague (1905), and again in Kristiania in 1918—its contents shifting as individual works were sold and new panels substituted. Though it never found a permanent home, the Frieze of Life remained Munch’s defining achievement, the anchor of his artistic identity.

On his seventy-fifth birthday, a photograph shows the painter standing in his studio at Ekely, surrounded by fragments of the cycle. The image is both poignant and emblematic: a man who spent his lifetime painting the soul, enclosed by the living remnants of his great unfinished poem in paint.

Munch Quiz

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.

Munch Crossword Puzzle

Instructions

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.

PC instructions; left click in the word space you want. Then type with your keyboard.

Mobile instructions: touch the word space you want to fill in. Then touch the little black squares at the bottom of the screen. That will bring up your keyboard. Type in the word.

Click Image