Salvador Dali

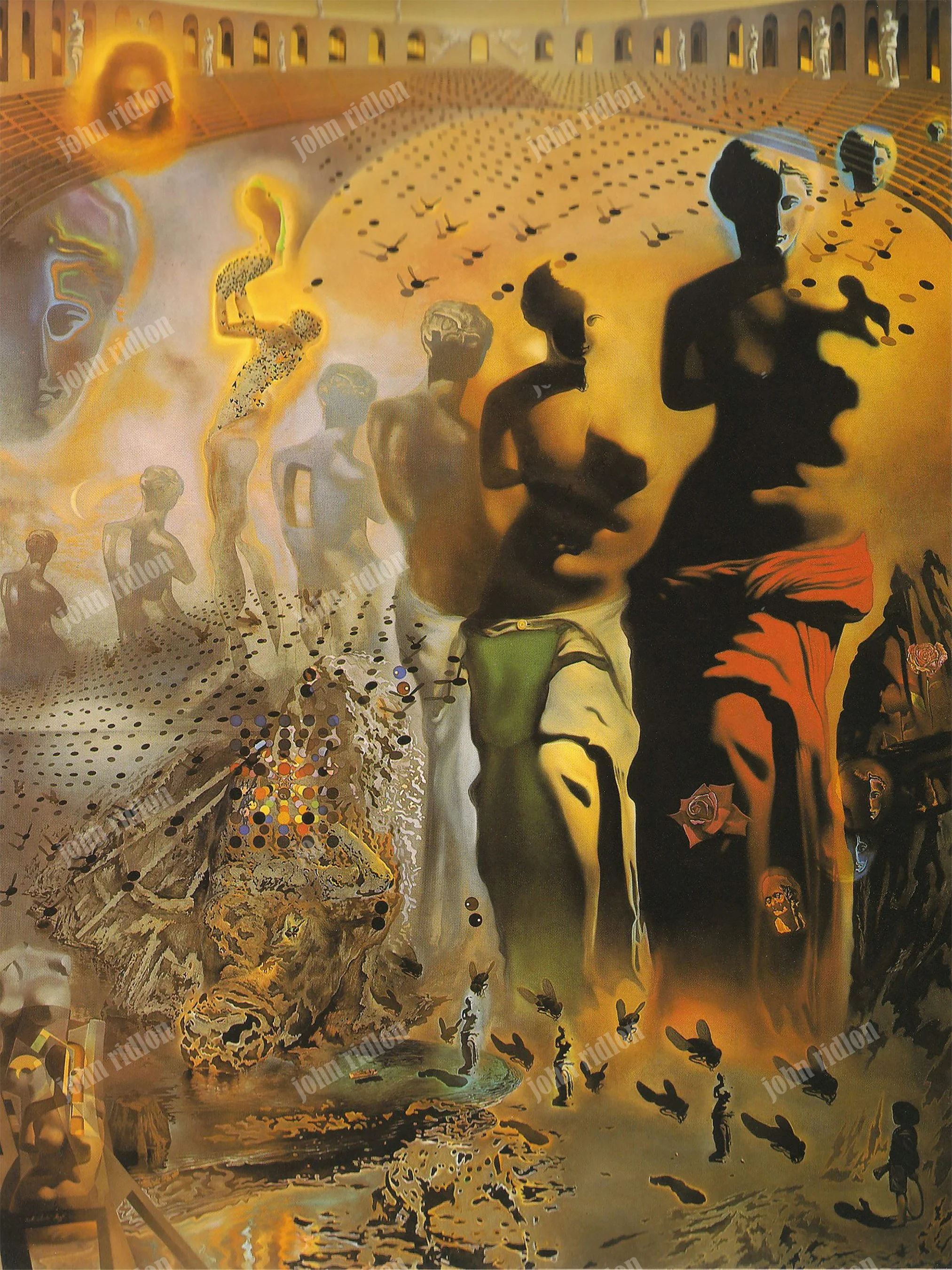

"The Hallucinogenic Toreador" (1969–1970)

Initial Version

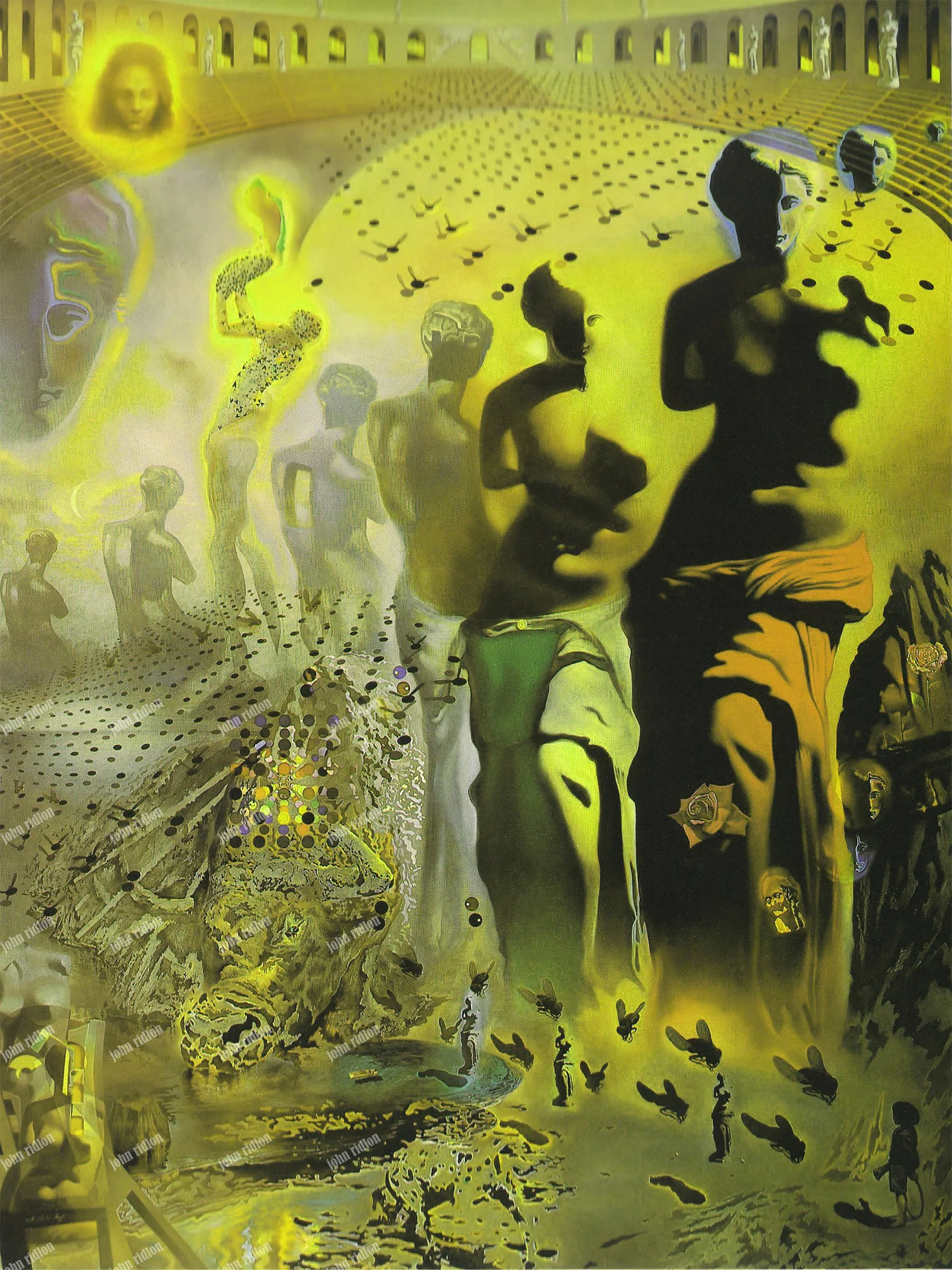

"The Hallucinogenic Toreador" (1969–1970)

Version 2

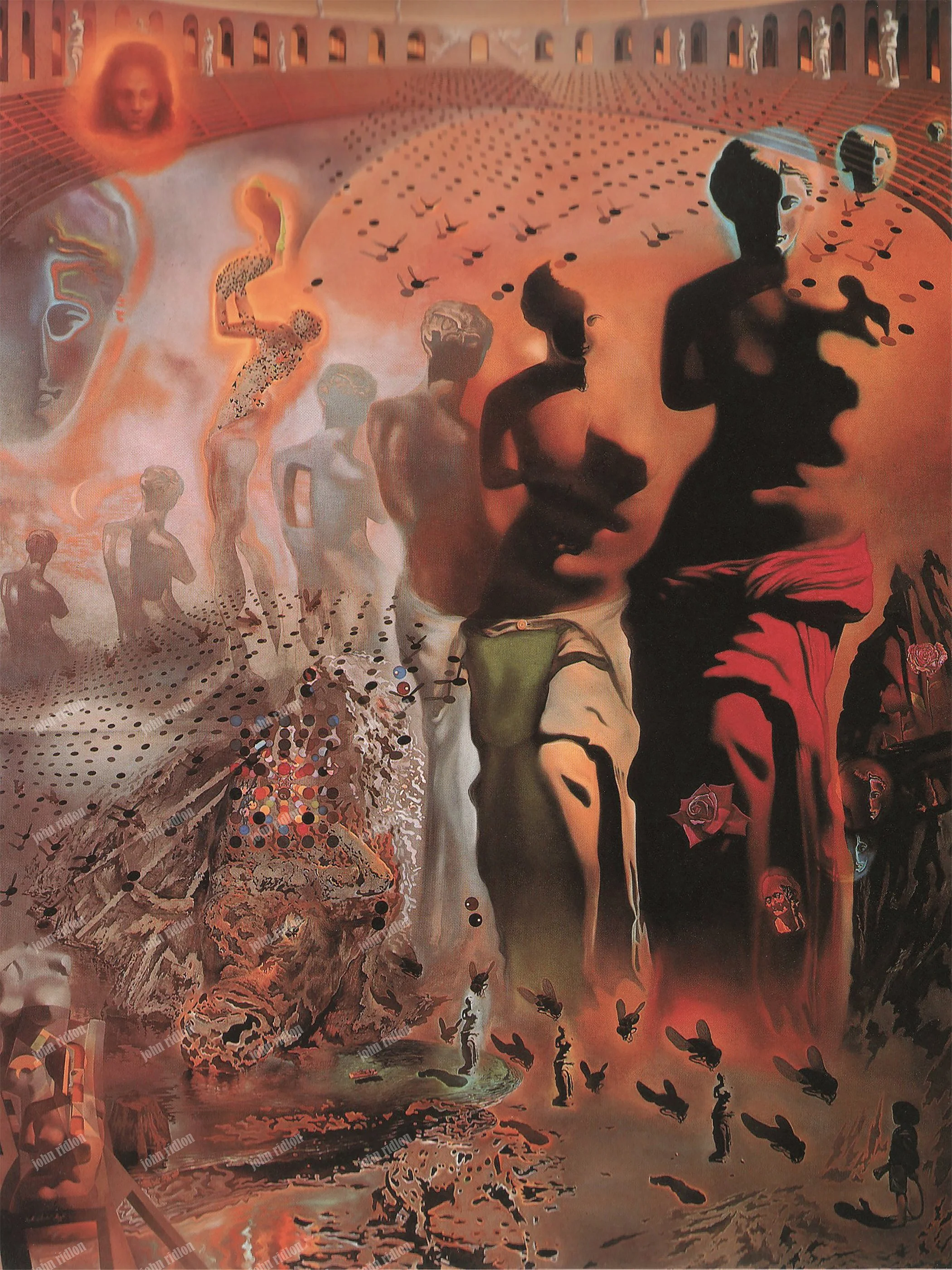

"The Hallucinogenic Toreador" (1969–1970)

Version 3

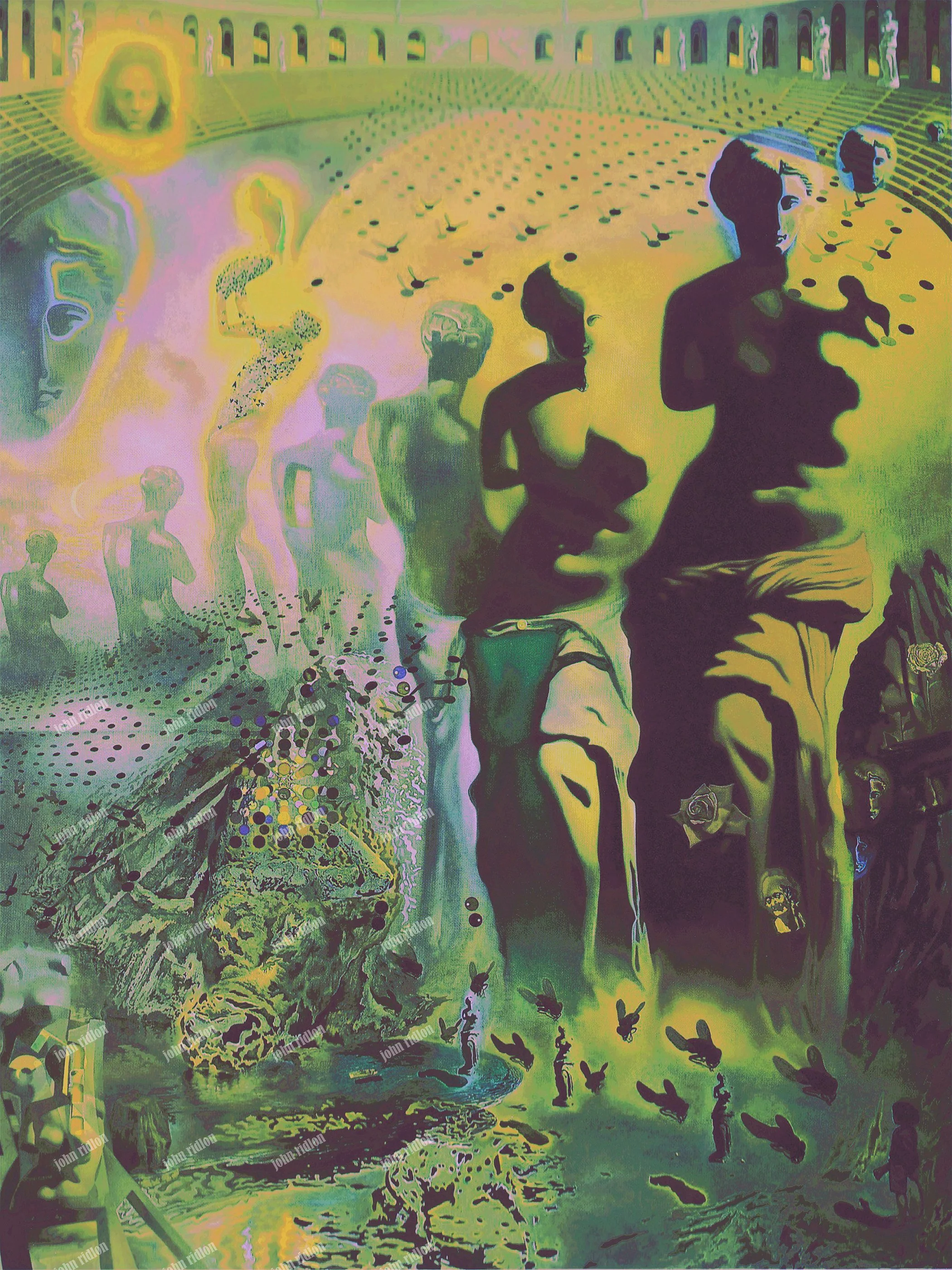

"The Hallucinogenic Toreador" (1969–1970)

Version 4

"The Hallucinogenic Toreador" (1969–1970)

Version 5

"The Hallucinogenic Toreador" (1969–1970)

Version 6

"The Dream" , 1930

Original Version

"The Dream" , 1930

Version 2

"The Dream" , 1930

Version 3

"The Dream" , 1930

Version 4

The Biography of Salvador Felipe Jacinto Dalí

The Making of Dalí: Genius, Rebellion, and Surrealist Fire

Salvador Felipe Jacinto Dalí was born on May 11, 1904, in Figueres, Catalonia. His father, a cultured but stern notary, maintained a library that sparked Dalí’s early fascination with literature and philosophy. His mother, Felipa Domenech, provided the warmth and emotional grounding of his childhood until her death in 1921—a loss that left a permanent scar on the young artist.

Summers in Cadaqués awakened Dalí’s imagination. The rocky coast, saturated with light and sea air, became a theater of hallucinations: animals, objects, scents, and dreams pulsed with hidden meaning. Recognized early for his talent, Dalí was mentored by family friends and artists such as the German painter Siegfried Burmann, who gifted him his first palette in 1914. By 1917, Dalí was formally studying drawing under Juan Núñez and exhibiting Impressionist-influenced landscapes at the Figueres Municipal Theater. He also co-founded the review Studium, writing with precocious authority on Goya, El Greco, Dürer, Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Velázquez—figures who would remain central to his artistic compass.

In 1921, Dalí entered Madrid’s San Fernando Academy and lived at the University Residence, a crucible of Spain’s cultural avant-garde. There he befriended Federico García Lorca and Luis Buñuel, immersing himself in Cubism, Futurism, and Purism, while studying the innovations of Picasso, Gris, Matisse, and De Chirico. Initially shy and eccentric, Dalí soon became notorious for his flamboyance. His first solo exhibition opened in 1925 at Barcelona’s Dalmau Gallery, showcasing works like Portrait of My Father and Girl Standing at the Window.

Dalí’s fierce independence led to expulsion from the Academy in 1926. That same year he traveled to Paris, where he met Picasso, returning to Madrid with sharpened conviction. A second solo show followed in 1927, alongside essays and polemics in avant-garde journals. His style edged toward Surrealism, reaching a breakthrough in 1929 with Un chien andalou, the dreamlike, shocking film co-created with Buñuel that propelled him into the Surrealist circle.

That year also brought Gala into his life—the Russian-born wife of poet Paul Éluard—who became his muse, lover, and eventual wife. Their relationship, both scandalous and fated, was as transformative as his art. Exhibitions in Zurich and Paris drew attention, with works such as Dismal Sport provoking equal measures of intrigue and outrage. In 1930, Dalí and Buñuel released L’âge d’or, another Surrealist film so provocative that it was violently suppressed by right-wing groups. At the same time, Dalí developed his “paranoiac-critical method,” formalizing the dream-logic of double images and delirious perception.

His union with Gala severed ties with his father but gave him an anchor of devotion. With the sale of The Old Age of William Tell, Dalí purchased a cottage in Port Lligat, which he and Gala transformed into their lifelong sanctuary by the sea.

By the end of the 1920s, Dalí had fully reinvented himself—from precocious dreamer to radical visionary. Through his early paintings, writings, and films, he had forged a Surrealist fire uniquely his own: irreverent, provocative, and utterly unforgettable.

In June 1931, Salvador Dalí exhibited 24 works at the Pierre Colle Gallery in Paris, including The Persistence of Memory—the now-iconic painting that would reappear in the Surrealist retrospective at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York the following year. That same year, he published Love and Memory, a poem steeped in his fascination with time, decay, and emotional distortion.

By 1932, Dalí and Gala were spending summers in Port Lligat, a remote fishing village that would become his lifelong retreat. Friends like René Crevel joined them, and Dalí continued to write and publish, including the film scenario Babaouo, though the project was never realized. To support his work, the Zodiac group formed—an elite circle of patrons who pledged to purchase one painting per month, providing Dalí with financial stability and creative freedom. His essays for Minotaure and illustrations for Les Chants de Maldoror showcased his growing influence in both literary and visual avant-garde circles.

Dalí’s earlier film L’âge d’or (1930), created with Luis Buñuel, had already stirred outrage with its anti-bourgeois provocations. Around this time, Dalí began to articulate his paranoiac-critical method—a technique of accessing subconscious associations through deliberate irrationality. His manifesto The Putrefied Donkey laid the groundwork for this approach, blending grotesque imagery with philosophical intent. His relationship with Gala deepened, becoming both muse and manager, though it fractured ties with his father. With proceeds from The Old Age of William Tell, Dalí purchased a modest cottage in Port Lligat, which he transformed into a surrealist sanctuary.

In 1934, Dalí arrived in New York and declared himself “the only true Surrealist.” He moved effortlessly between press conferences and high-society galas, cultivating a persona as flamboyant as his art. His essay The Conquest of the Irrational (1935) formalized his artistic philosophy, arguing that irrationality was not chaos but a gateway to deeper truths. By 1936, Dalí was living near Sacré-Coeur in Paris and gave a now-legendary lecture while wearing a deep-sea diving suit to symbolize his descent into the subconscious. The stunt nearly ended in disaster when he began to suffocate mid-talk, unable to remove the helmet. Rescued just in time, the incident became emblematic of Dalí’s blend of danger, drama, and devotion to the surreal.

The Spanish Civil War forced Dalí and Gala to flee Port Lligat. In December 1936, Dalí appeared on the cover of Time magazine, cementing his fame in the United States. His 1937 visit to Hollywood led to a surreal collaboration with Harpo Marx and the unproduced script Giraffes on Horseback Salad. That same year, he exhibited Metamorphosis of Narcissus in Paris and met Sigmund Freud in London—a pivotal moment in his intellectual development and validation of his paranoiac-critical method.

Despite growing tensions with the Surrealist group, Dalí continued to participate in exhibitions. His Rainy Taxi installation in 1938 was a sensation, blending absurdity with spectacle. He caused further scandal with his provocative window display at Bonwit-Teller and his Dream of Venus pavilion for the 1939 World’s Fair. That same year, his ballet Bacchanale premiered at the Metropolitan Opera, with Dalí designing both sets and costumes—melding classical performance with surrealist vision.

As World War II loomed, Dalí returned to the U.S. in 1940, settling first in Virginia. His creative output exploded: he designed another ballet, Labyrinth, and held a major retrospective at MoMA in 1941. He ventured into jewelry, advertising, literature, and stage design. His autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, was published in 1942, offering a flamboyant and introspective account of his life. Around this time, he met Eleanor and A. Reynolds Morse, who would become lifelong patrons and collectors of his work.

In 1945, Dalí collaborated with Alfred Hitchcock on Spellbound, contributing dream sequences that blurred the line between cinema and subconscious. He also worked with Walt Disney on Destino, a short film that remained unfinished for decades. Dalí continued to exhibit across the U.S. and illustrated works by Cellini, Montaigne, and Shakespeare. Returning to Europe in 1949, he presented Madonna of Port Lligat to Pope Pius XII and collaborated with Luchino Visconti on As You Like It.

His Mystical Manifesto (1951) marked a turn toward Catholic themes and metaphysical inquiry. Dalí’s public appearances became increasingly theatrical, including a 1958 lecture where he was followed by a 12-meter loaf of bread. His ballet Le ballet de Gala premiered in Venice in 1961. In 1962, he unveiled Battle of Tetuan in Barcelona and published The Tragic Myth of Millet’s Angelus and Diary of a Genius, further blending art, autobiography, and metaphysics.

Dalí’s Perpignan Station was exhibited in 1965, followed by a massive show of 370 works in New York. In 1974, he inaugurated his Theater Museum in Figueras—a surrealist temple and immersive archive of his life’s work. He was elected to the Académie Française in 1979 and honored with a retrospective at the Pompidou Center. Gala’s death in 1982 devastated him. That July, King Juan Carlos of Spain named him Marquis of Púbol.

In his final years, Dalí lived with the solemnity of a monarch. He attempted suicide, suffered burns in a fire, and withdrew into seclusion. He died on January 22, 1989, leaving behind a legacy as singular as his imagination—an oeuvre that blurred the boundaries between art and dream, reason and madness.

At Masterwork Prints, we honor artists like Dalí who defied convention, embraced contradiction, and transformed the visual language of the twentieth century. His journey reminds us that genius often walks hand-in-hand with madness—and that both can be profoundly beautiful.

For best results in solving the quiz and the puzzle please refer back to the listed paintings and the biography which are all within the artist's tab.

Salvador Dali Crossword Puzzle

Click the Image