Gustav Klimt

Symbolism

Gustav Klimt: Landscapes of Silence and Sensation

Gustav Klimt is widely known as a painter of women, a visionary portraitist, and a cultural force in turn-of-the-century Vienna. Yet nearly half of his late oeuvre consists of landscapes—works created not for patrons, but for personal pleasure and the open market. These paintings, often dismissed or misunderstood in his lifetime, now reveal the full depth of his artistic sensibility.

Klimt’s landscapes are not mere depictions of nature. They are meditations on form, color, and stillness. Created during his retreats to the Salzkammergut, they reflect a duality in his life: the public figure at the center of Viennese artistic reform, and the private man seeking solitude and serenity. These works are pure presence—motionless, timeless, and meticulously composed. They have been compared to still lifes, not only for their quietude but for their formal rigor.

Unlike his allegorical paintings or society portraits, which often mask their subjects in ornament and distance, Klimt’s landscapes speak in a direct, unfiltered language. They reveal his mastery of color, his sensitivity to surface, and his openness to international artistic currents. In these works, Klimt absorbed and reimagined the innovations of his time—drawing from the Secession’s global connections and adapting new visual technologies like telephotography to frame and distance the land.

Critics once scoffed at their otherworldliness—“Klimt’s landscapes should be in an exhibition on Mars or Neptune,” one wrote in 1903. But that alien quality was precisely the point. Klimt sought an “elsewhere,” a utopia of visual harmony that could transcend the discord of modern life. His landscapes are not records of place, but visions of order and peace.

As Peter Peer and Anselm Wagner have shown, Klimt’s landscapes are deeply rooted in Austrian tradition, yet radically modern in their conceptual ambition. They merge Natur and Kultur—nature without movement, culture without gesture—into a unified stillness. In doing so, Klimt redefined the genre, using landscape as a vehicle for introspection, escape, and aesthetic clarity.

To study these paintings is to encounter the complete Klimt: his formal boldness, his sensual restraint, his search for purity. They are not just beautiful—they are revelations.

Gustav Klimt: From Cultural Ornament to Artistic Iconoclast

Before Gustav Klimt became the painter of shimmering women and meditative landscapes, he earned his reputation as a devoted servant of imperial culture. In the 1880s, Klimt and two college friends formed a decorative arts partnership that won state commissions for architectural embellishment. Their work adorned provincial theaters and two of Vienna’s grandest Ringstrasse buildings: the Burgtheater and the Kunsthistorisches Museum. These early works reflect Klimt’s “Age of Innocence”—a time when artist, patron, and empire were united in the pursuit of high culture.

But Klimt’s trajectory was anything but static. By the turn of the century, he had become the face of the Secession movement, leading a revolt against academic tradition and bourgeois taste. His allegorical works—Theseus and the Minotaur, Nuda Veritas, and the Beethoven Frieze—offered bold new symbols for a modern age. In these, Klimt reimagined the artist not as a craftsman of state ideals, but as a Promethean figure: autonomous, erotic, and redemptive.

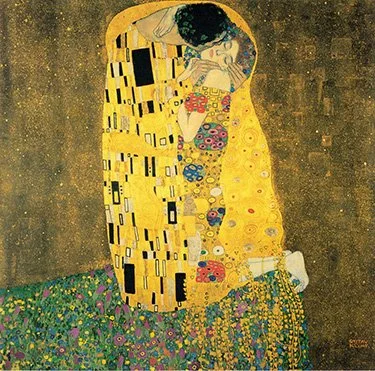

The 1902 Beethoven Exhibition was a watershed moment. Klimt’s frieze, inspired by Schiller’s “Ode to Joy,” transformed the idea of human fraternity into a vision of sensual fulfillment. The artist was no longer a mirror of society, but its redeemer—his kiss a symbol of transcendence, not politics.

By 1908, the Kunstschau exhibition shifted focus from ideology to integration. Klimt and his collaborators presented Wohnkultur—a vision of art permeating everyday life. The show featured a model house, ceramics, sculpture gardens, and even a cemetery. At its center stood the Klimt Hall, filled with portraits and landscapes painted during his retreat from public controversy. One critic called the exhibition “a festive garment wrapped around Klimt.”

These later works—especially the landscapes—reveal a quieter, more introspective Klimt. They mark his transition from public artist to private seeker, from cultural ornament to modern iconoclast. His journey reflects the broader transformation of Viennese art: from imperial grandeur to personal truth, from tradition to modernity.

Gustav Klimt: From Public Culture to Private Vision

When Gustav Klimt opened the Kunstschau in 1908, he did so with a quiet but radical proposition: to rebuild the bond between artist and public—not through state commissions or grand cultural projects, but through the exhibition itself. In his address, Klimt echoed a longing for the lost unity of the Ringstrasse years, when artist, patron, and empire shared a vision of high culture. Now, in a more fragmented age, he turned to William Morris’s ideal: that even the smallest crafted object could enrich the world, and that true culture meant infusing all of life with artistic intention.

Klimt envisioned a Künstlerschaft—an ideal community of creators and appreciators, united by beauty. The Kunstschau offered models for this aesthetic lifestyle, from architecture and ceramics to gardens and portraiture. Peter Altenberg’s aphorism—“Art is art and life is life, but to live life artistically, that is the art of life”—captured the spirit of the moment. Klimt’s collaboration with Josef Hoffmann on the Stoclet Palais exemplified this union of artist and designer, even as Klimt maintained the distinction between the two.

In Klimt’s mature portraits, the decorative setting often rivals the figure itself. His women seem suspended in a transcendent space—an enclosed world of beauty, untouched by the noise of everyday life. This shift from public painter to private aesthete marked a turning point in Klimt’s career, and it gave new meaning to his landscapes.

Landscapes as Utopia

Klimt’s landscapes, created during his summer retreats, reflect a vision of nature purified and ordered—a kind of Rosenhaus, a garden of serenity. Like Adalbert Stifter’s Nachsommer, in which a disillusioned bureaucrat retreats to a house of perfect harmony, Klimt’s hillsides and distant vistas offer a refuge from the discord of modern life. His landscapes are not records of place, but expressions of peace, crafted with the same care as his ornamental portraits. In this context, Klimt’s landscapes are doubly significant: they represent both an aestheticist turn and a reawakening of Austrian tradition. Nature, in Klimt’s hands, becomes a canvas for selection and refinement. Dissonance is removed. Light is controlled. The world blooms as it should—not as it is.

Art and Nature: A Philosophical Reflection

“Art is the opposite of nature,” Klimt once said. “A work of art comes from the inner soul of a human being… Nature is the infinite realm from which art takes its nourishment.” For Klimt, nature was not just what the eye sees—it was also the soul’s inner image, the vision behind the eye. His art was a crystallization of feeling, a distillation of experience into form.

In the end, Klimt’s landscapes and portraits converge in their stillness, their order, their quiet transcendence. They are not just beautiful—they are philosophical. They ask us to imagine a world shaped by art, where life itself becomes a crafted experience.

The Kiss, 1908

Judith and the Head of Holofernes, 1901

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, 1907

Hope II, 1908

The Three Ages of Woman, 1905

Mäda Primavesi,1913

Hygieia, 1907

"The Maiden", 1913

Water Serpents II (Wasserschlangen II), 1904