Edgar Degas

The Ballet Class, 1874

The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage, 1874

The Dance Class, 1874

Dancers, Pink and Green, 1890

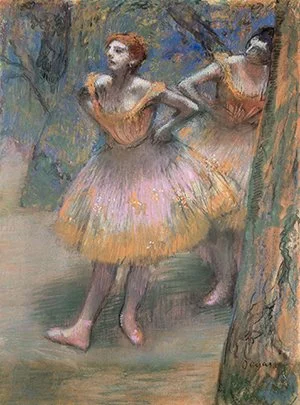

Two Dancers, 1895

Frieze of Dancers, 1895 Initial Version

Edgar Degas: A Modern Master in Motion

Even during his lifetime, Edgar Degas was recognized as a modern master. Since his death in 1917, his reputation has only grown—his work remains strikingly alive, admired for its originality, sharp wit, and unflinching visual intelligence. Degas didn’t just observe the world around him—he dissected it, revealing its rhythms, tensions, and quiet truths.

He lived through a period of profound transformation. France was reshaped by industrialization, and Paris—the city of his birth and lifelong residence—underwent dramatic reinvention. The Paris that emerged during the Second Empire and the early Third Republic became Degas’ canvas: a city of movement and spectacle, populated by dancers, jockeys, café-goers, and workers. Born into a wealthy banking family, Degas chronicled the rituals and refinements of the haute bourgeoisie, but his gaze extended beyond privilege. He captured the grit and grace of the city’s working class, revealing a Paris that pulsed with complexity.

A Career in Three Acts

Degas’ artistic journey unfolded in three distinct phases:

• 1855–1865: The Aspiring Historian

In his early years, Degas sought to establish himself as a history painter in the grand academic tradition. He studied the old masters with reverence, absorbing their techniques and ideals.

• 1865–1885: The Realist and Impressionist Ally

This middle period marked his shift toward Realism and his close association with the Impressionist circle. Though he resisted the label, Degas shared their interest in capturing modern life—its fleeting gestures, its unguarded moments. His work from this era is grounded in observation, yet charged with psychological insight.

• 1885 Onward: The Aesthetic Explorer

In his final decades, Degas became increasingly preoccupied with form, movement, and the expressive possibilities of the human body. Ballet dancers, bathers, and women at work became his central subjects. He pushed his technique into new territory, experimenting with pastel, monotype, and unusual compositions. His admiration for classical art never waned, but he fused it with a restless modernity that made his work utterly unique.

Degas was a paradox: a traditionalist who revolutionized modern art. He revered the past but refused to be bound by it. His legacy is one of tension and transformation—a mirror of the world he lived in, and a testament to the power of seeing deeply.

Edgar Degas lived for his art. He never married, and his personal life remains largely veiled—known only through the quiet recollections of close friends. What is clear is that his devotion to painting was total, and his pursuit of mastery relentless.

Romanticism and Revolution

By the 1820s, the classical ideals that had dominated French art began to fracture. A new movement emerged—Romanticism—led by Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix. Ironically, its roots lay in the innovations of Davidian-trained painters like Baron Gros, who had already begun to infuse historical painting with drama and emotion.

Delacroix believed that the classical tradition needed renewal—something more attuned to the turbulence of the age. France had endured revolution, war, restoration, and upheaval. To poet Charles Baudelaire, Delacroix’s bold compositions and vivid brushwork captured the volatility of the times. His art was not just visual—it was psychological, political, and deeply personal.

The Rivalry: Ingres vs. Delacroix

By the 1840s, the French art world was polarized by the rivalry between Ingres and Delacroix. Ingres, a champion of line and clarity, looked to Raphael and Poussin. Delacroix, with his passion for color and movement, drew inspiration from Titian, Rubens, Rembrandt, and Michelangelo.

Their contempt for each other was legendary. When Delacroix was finally elected to the Academy, Ingres voted against him. Their feud became a defining debate for a generation of artists—including Degas.

Historical Drama and Artistic License

Amid this tension, Paul Delaroche pioneered the genre historique—melodramatic scenes from history, rendered with theatrical lighting and emotional intensity. His Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833) is a prime example: blindfolded, pale, and reaching for the block, Jane’s portrayal is more fiction than fact. But it struck a chord with audiences, blending sentiment with spectacle.

Italy: Classical Roots and Personal Discovery

Though France had become the epicenter of the art world, Italy’s classical heritage still held sway. In 1856, Degas set sail for Naples, staying at his grandfather’s palazzo. He immersed himself in the Museo Nazionale Romano, studying murals from Pompeii and masterpieces by Titian and Veronese. He read Dante, sketched the Sorrento coast, and made portraits of his family—most notably his troubled aunt Laura Bellelli.

Rome: Art, Antiquity, and the Caldarrosti

In Rome, Degas explored the Vatican’s treasures—Leonardo’s Saint Jerome, Canova’s Perseus, and the Papal collection of classical statuary. He copied Domenichino’s frescoes, studied mosaics attributed to Giotto, and sketched the Roman Forum and Villa Borghese Gardens. He also joined a circle of young artists known as the Caldarrosti—named after the roast chestnut vendors of Rome. They met at the Caffé Greco to discuss art, music, and literature. Goethe, Byron, Shelley, Leopardi, Stendhal, and Berlioz were frequent topics, as were the merits of Ingres and Delacroix. Degas began work on religious and mythological subjects, including studies for Saint John the Baptist and the Angel and paintings inspired by Dante. But doubt plagued him, and many of these projects we

Naples, Florence, and the Bellelli Family

In August 1857, Degas returned briefly to Naples to copy Pompeian murals. By mid-October, he was back in Rome, where he grew close to Gustave Moreau. Under Moreau’s influence, Degas began to appreciate the expressive power of Delacroix, Rembrandt, and the Venetian masters.

After short stays in Arezzo, Assisi, and Perugia, Degas arrived in Florence in August 1858. He lodged with his aunt Laura Bellelli, whose quiet strength and troubled marriage would later inspire The Bellelli Family—his most accomplished painting to date. It marked a shift in Degas’ art: from classical study to psychological depth, from tradition to modernity.

In Florence, Degas returned to work with intensity. He studied the Florentine masters, read Pascal’s Pensées, and sketched mythological and historical subjects including David and Goliath and Blind Oedipus. Yet beneath the discipline, a melancholy stirred. “There is an emptiness that even art cannot fill,” he wrote to Gustave Moreau—a line that reveals the emotional weight of this period. His grandfather’s death and the temporary absence of his aunt Laura Bellelli added to the sense of loss.

When Laura returned, Degas focused his energy on preparatory sketches for her portrait. By spring, with Moreau preparing to leave Italy and the Paris Salon looming, Degas was eager to return to France. He wrote to his father, urging him to find a studio where he could complete the portrait.

The Bellelli Family: A Portrait of Distance

Regarded as Degas’ first true masterpiece, The Bellelli Family is a psychological group portrait of remarkable depth. Laura Bellelli sits in mourning for her father, her refined features echoing the influence of Ingres and Bronzino. Her daughters, Giulia and Giovanna, are positioned with subtle contrast—one formal, one relaxed—while her husband, Gennaro, sits apart at his desk, absorbed in business.

The composition is pyramidal, yet fractured. The emotional distance between Laura and Gennaro is palpable. Degas produced many studies in search of a form that could express the tension, restraint, and quiet sorrow of this family. It’s a painting not just of people, but of relationships—of silence, separation, and the weight of domestic life.

A Changing Art World: The Rise of Modernism

The 1860s marked a turning point in French art. The deaths of Delaroche, Delacroix, and Ingres signaled the end of an era. New movements—Realism, Naturalism, and a late Romanticism—began to challenge the dominance of classical and academic traditions.

Discontent with the Academy’s rigid standards led to public protests. In 1863, Napoleon III authorized the Salon des Refusés, giving rejected artists a platform. Though Degas did not exhibit, the show featured works by Manet, Whistler, Fantin-Latour, Pissarro, and others. Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe was harshly criticized, but its impact on younger artists was profound.

The Salon des Refusés undermined the Academy’s authority and encouraged alternative venues. That same year, the École des Beaux-Arts underwent reform, appointing younger professors and adopting more liberal teaching methods. As France invested in industrial modernization, state funding for the arts declined, and commissions for grand history paintings dwindled. A new art economy emerged—one driven by private galleries and public taste.

Changing Tastes: Realism and the Rise of Landscape

The Second Empire’s economic boom brought new buyers into the art market. Their tastes were eclectic, and Realism began to flourish. Artists like Courbet and Millet gained recognition for their honest depictions of rural life and labor. Meanwhile, Fantin-Latour, Legros, and Whistler carried forward Delacroix’s legacy in more intimate, poetic forms.

Landscape painting also underwent a transformation. The Barbizon painters—Daubigny, Rousseau, Troyon, Diaz de la Peña, and Corot—abandoned idealized vistas in favor of direct observation. Sketching en plein air, they captured nature’s immediacy and atmosphere. Their influence on Degas and the Imressionists would be lasting.

Painting Modern Life: Degas and the Pulse of Paris

By the late 1850s, a new idea was gaining ground in French art: that painting should reflect the present, not the distant past. Writers and critics began to champion art that captured the world around them—its people, its streets, its shifting moods. This cultural shift gave rise to movements that would redefine the very purpose of painting.

Émile Zola, one of the most influential voices of the time, made his mark with gritty novels that exposed the underbelly of Parisian life. He also emerged as a powerful art critic, urging artists to embrace personal expression and to draw inspiration from the realities of Second Empire France. His vision of art as a mirror to society resonated deeply with Degas.

Baudelaire and the Spirit of Modernity

Among the writers who shaped this new sensibility, none was more influential than Charles Baudelaire. A close friend of Manet and a passionate admirer of Delacroix, Baudelaire saw Paris as both a city of dreams and disillusionment. His poetry captured the beauty and alienation of modern life, and his critical essay The Painter of Modern Life became a manifesto for a new generation of artists.

Published in 1863, Baudelaire’s essay celebrated the work of Constantin Guys, a popular illustrator of Parisian street life. But it was more than a tribute—it was a call to arms. Baudelaire urged artists to find “that indefinable something we may be allowed to call modernity… the transient, the fleeting and the contingent.” He believed that the artist’s task was to capture the poetry of the everyday, to find meaning in the moment. Degas absorbed these ideas deeply. Like Guys, he cultivated wit, curiosity, and a sharp eye for detail. His depictions of dancers, laundresses, and café-goers reflect Baudelaire’s vision of the city—its elegance, its exhaustion, its quiet drama.

The Origins of Impressionism

Degas was closely aligned with the Impressionists, though his work often diverged from theirs in technique and temperament. Impressionism grew out of debates about realism, perception, and the role of the sketch in capturing fleeting impressions. Romantic artists had already begun to value the oil sketch as a pure expression of artistic thought, and collectors responded with enthusiasm.

The term “Impressionist” was first used mockingly by critic Louis Leroy in 1874, in response to Monet’s Impression, Sunrise. But the artists embraced it. Degas, along with Monet, Morisot, Pissarro, Renoir, Sisley, Cézanne, Guillaumin, and Caillebotte, exhibited together in eight group shows between 1874 and 1886. Their work reflected a growing desire for contemporary subject matter and a break from academic tradition.

Degas’ approach was more structured than many of his peers. He was less concerned with light and atmosphere, more focused on form, movement, and psychological nuance. Yet his commitment to modern life placed him firmly within the Impressionist circle.

A Changing Art World

The 1860s marked a turning point in French art. The deaths of Delaroche, Delacroix, and Ingres signaled the end of an era. New styles—naturalism, realism, and a late romanticism—began to challenge the dominance of classical ideals.

Public dissatisfaction with the Academy’s rigid standards led to protests and reforms. The Salon des Refusés of 1863 gave rejected artists a platform, and though Degas did not participate, the event reshaped the art world. Manet’s controversial Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe shocked critics but inspired younger artists to seek new paths.

The École des Beaux-Arts was restructured, and state funding for the arts declined as resources shifted toward industrial modernization. Private galleries began to flourish, and artists like Degas found new ways to build their careers outside the official system.

Oscar-Claude Monet

Claude Monet: The Making of an Impressionist

The name Claude Monet is virtually inseparable from the movement he helped define—Impressionism. It was one of his own paintings, Impression, Sunrise (1872), that gave the movement its name. More than any of his contemporaries, Monet remained steadfast in his pursuit of capturing fleeting light, atmospheric nuance, and the totality of a moment. He was prolific, uncompromising, and often insatiable—never satisfied with the quality of light, the time available, the money earned, or the recognition received.

To be close to Monet in his early years was to shoulder a burden of emotional and financial support. His friend Frédéric Bazille, generous and kind-hearted, learned this firsthand. Yet the struggling painter who once bartered caricatures and painted on scraps would, in time, become a lionized figure—commanding thousands of dollars for a single canvas of a grain stack and skillfully navigating art dealers to ensure his prices remained high.

Origins in Normandy

Claude Oscar Monet was born in Paris on November 14, 1840, the younger of two sons. When he was five, his father Adolphe moved the family to Le Havre, a bustling port city on the Normandy coast, where he joined the Lecadres, relatives who ran a successful wholesale and ship chandlery business.

From an early age, Claude showed a natural talent for drawing. At the Collège du Havre, he studied under Charles Ochard, a teacher who had trained under Jacques-Louis David, the famed Neo-Classicist and court painter to Napoleon I. Yet Monet was never a model student. “I more or less lived the life of a vagabond,” he recalled in 1900. “By nature I was undisciplined; never, even as a child, would I submit to rules.”

School felt like confinement. The sea, the sun, and the open air called to him more than any classroom. By fifteen, he had become locally famous for his irreverent caricatures of teachers—drawn with biting humor and bold lines. But beneath the mischief lay a serious artistic impulse, nurtured by his aunt, Mme Lecadre, an amateur painter who took a deep interest in his development, especially after the death of his mother in 1857.

Monet’s growing devotion to art strained his relationship with his father, who wanted him to complete his education and pursue a stable career. Mme Lecadre, with the help of painter Armand Gautier, persuaded Adolphe to let Claude follow his passion. Monet skipped the baccalaureate exam and left school with no formal qualifications—only a fierce belief in his own path.

A Revelation in the Landscape

Though gifted, Monet lacked formal training, and his rebellious nature made him resistant to academic instruction. A pivotal moment came when Gravier, a local frame-maker who displayed Monet’s drawings in his shop, introduced him to Eugène Boudin, a respected landscape painter.

Monet was initially dismissive. He found Boudin’s work crude and disliked the naturalistic style, having been accustomed to the stylized, fantastical compositions popular at the time. But Boudin persuaded him to join a plein air painting excursion. The experience was transformative.

“I understood,” Monet later said. “I had seen what painting could be, simply by the example of this painter working with such independence at the art he loved. My destiny as a painter was decided.”

From that moment, Monet embraced the outdoors as his studio. The changing light, the movement of clouds, the shimmer of water—these became his subjects, his obsession, and eventually his legacy.

Paris Beckons

Monet applied for a municipal grant to study art in Paris but was rejected. Undeterred, he gathered his savings—mostly earned from caricature commissions—and set off for Paris in the spring of 1859. Armed with letters of introduction from Boudin, he met several artists, including Troyon and Gautier. Troyon saw promise in the young painter and recommended he enroll at the atelier of Thomas Couture, a respected teacher whose students included Édouard Manet.

Monet refused. He disliked the rigidity of academic instruction and returned to Le Havre. But the pull of Paris was strong. By the winter of 1860, he was back—this time drawing live models at the free Académie Suisse. It was there that he met Camille Pissarro, a fellow artist who would become a lifelong friend and collaborator. Their meeting marked the beginning of a new chapter—not just for Monet, but for the birth of a movement that would change the course of art history.

Defiance and Discovery: Monet’s Military Interlude

In 1861, Claude Monet’s name was drawn for military service—a seven-year commitment that many young men dreaded. Families with means could pay to exempt their sons from the draft, and Adolphe Monet offered to do just that—on one condition: Claude must abandon art and join the family business. Monet refused. With characteristic stubbornness, he enlisted in the Chasseurs d’Afrique, a cavalry unit stationed in Algeria.

The North African landscape left a lasting impression. The clarity of light, the vastness of space, and the vibrancy of color would echo through Monet’s later work. But his time there was cut short. Within a year, he contracted typhoid and returned to France to recover.

During this period, Monet met Johan Barthold Jongkind, a Dutch painter of land and seascapes. Jongkind became what Monet later called his “true master…the final education of my eye.” His influence was profound—encouraging Monet to see nature not just as subject, but as atmosphere, as light in motion.

A Deal and a New Direction

Mme Lecadre, Monet’s devoted aunt, remained convinced of his potential. She offered to buy him out of the army, and a compromise was reached with Adolphe: Monet would receive a modest allowance to study art in Paris, provided he enrolled in a formal atelier.

Monet chose the studio of Charles Gleyre, a Swiss painter known for his interest in landscape and his training of students for the Prix de Paysage Historique. Gleyre’s atelier was affordable—he charged only for models and materials, not instruction—which suited Monet, whose father kept him on a tight financial leash.

The Birth of a Brotherhood

In 1862, Monet began his studies at Gleyre’s atelier and quickly formed bonds with fellow students Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille, and Alfred Sisley. Within months, Monet was leading them on plein-air painting excursions to the Fontainebleau Forest and the countryside around Paris.

By 1863, French art was in upheaval. Édouard Manet had scandalized the Salon des Refusés with Luncheon on the Grass, challenging academic norms with bold composition and modern subjects. Monet, still unknown, was quietly forging his own path—rejecting Gleyre’s teachings and pursuing a rigorous program of self-improvement.

When Gleyre retired in 1864, Monet was 24 and free to chart his own course, though still financially dependent on his father. Bazille stepped in, offering not just money but companionship. The two shared a studio on rue Furstenberg between 1865 and 1866. Bazille’s death in the Franco-Prussian War was a devastating loss—both personal and artistic.

First Successes and Artistic Evolution

By the Salon of 1865, Monet had achieved modest recognition. Two of his landscapes were accepted and exhibited, receiving mixed reviews. One critic praised him as “a young Realist who promises much,” while another dismissed his work as childish. Yet Monet’s obsession with light and color was unmistakable. Influences from Boudin, Jongkind, Manet, and Courbet were present, but his style was evolving—moving away from Realism toward something more atmospheric, more ephemeral.

During this time, Monet began experimenting with large-scale figure compositions. His own Luncheon on the Grass—never completed—was an ambitious attempt to integrate figures and light into a unified plein-air composition. Art historian Forge described it as an effort to “monumentalize the language of a plein-air sketch.”

Injury, Frustration, and Friendship

The project was bold, but perhaps doomed. Monet lacked the studio space, time, and financial stability to finish it. In 1865, he injured his leg and was confined to bed at the Cheval-Blanc Inn in Chailly, where he had been working on the painting.

Bazille, who had abandoned medicine to pursue art, used his medical knowledge to ease Monet’s pain—rigging a device to drip water onto the injured leg. A poignant portrait by Bazille, Monet après son accident, shows the artist lying in bed, impatient and irritable, waiting for Bazille to arrive and model. The painting is more than a depiction—it’s a testament to the depth of their friendship and Bazille’s unwavering support.

This chapter in Monet’s life is a study in contrasts: defiance and dependence, ambition and limitation, solitude and solidarity. It marks the emergence of a painter who would soon redefine the language of light—and the beginning of a movement that would change the course of art history.

Struggle, Love, and Artistic Resolve (1867–1871)

By 1867, Claude Monet’s life was unraveling. His relationship with Camille-Léonie Doncieux—his model, muse, and lover—had drawn the ire of both his father, Adolphe, and his aunt, Mme Lecadre. Camille had posed for several figures in Luncheon on the Grass and for Monet’s ambitious new canvas Women in the Garden, which was ultimately rejected by the Salon. Their romance, already strained by financial instability, was now under siege from their families.

Monet was drowning in debt. Camille was pregnant. The modest 800 francs he had earned from the Salon of 1866 had long since vanished. Under pressure from Aunt Lecadre and Adolphe, Monet was forced to retreat to Sainte-Adresse on the Normandy coast. Camille remained in Paris, where she gave birth to their son Jean in July—alone, ill, and destitute.

In a letter to Bazille that May, Monet confessed his despair: Camille was “ill, bedridden and penniless,” and he didn’t know what to do. He reminded Bazille of a fifty-franc debt due by the first of the month. Bazille, ever loyal, bought Women in the Garden for 2,500 francs—payable in monthly installments. But Monet’s desperation deepened. In June, he asked for another 100 or 150 francs. By August, he wrote a heartbreaking plea: “Really, Bazille… there are things that can’t be put off until tomorrow. This is one of them and I’m waiting.”

Sainte-Adresse and the Maturing Eye

Despite the emotional turmoil, Monet’s enforced stay at Sainte-Adresse yielded a series of beach scenes that revealed a growing maturity in his vision. The brilliant sunlight, however, caused severe eye strain, forcing him to stop painting that autumn.

The following year brought mixed fortunes. Monet sold a full-length portrait of Camille—Woman in the Green Dress—to Arsène Houssaye, editor of L’Artiste, and received a commission to paint Mme Gaudibert, the wife of a Le Havre notable. Yet creditors seized his paintings at an exhibition in Le Havre, and the strain on his relationship with Camille, now caring for a newborn, was immense.

In June 1868, the family was evicted from a country inn. Monet, overwhelmed, confessed in a letter to Bazille that he had attempted suicide. Whether this was a genuine act or a dramatic expression of despair is unclear—Monet’s letters often veered into bathos. But the pain was real.

By December, the tide had turned. Thanks to the patronage of M. Gaudibert, Monet, Camille, and Jean were living in a small cottage in Etretat. Monet was ecstatic. “Surrounded by my family and able to work in peace,” he wrote to Bazille. Reflecting on his art, he added: “The further I get, the more I realize that no one ever dares give frank expression to what they feel.”

The Birth of Impressionism

In the summer of 1869, Monet began to do just that. Working alongside Renoir at La Grenouillère on the Seine, he produced what are now considered the first truly Impressionist paintings. Monet dismissed them as “rotten sketches,” but signed them nonetheless. They were studies for a larger, now-lost canvas—known only through a faint photograph—but the surviving works reveal the essence of the movement: fluid brushwork, fleeting light, and atmospheric immediacy.

At this point, the distinction between sketch and finished painting was beginning to dissolve. Monet was painting wet-on-wet, using swift, confident strokes to blend color directly on the canvas. This technique matured in Trouville the following summer and reached new heights during his exile in London from 1870 to 1871.

Exile and Reinvention in London

Monet had just married Camille when the Franco-Prussian War broke out. To avoid conscription, he fled to London. The city was unfamiliar, its climate mercurial, its fogs legendary. “I endured much poverty,” he recalled in 1900. Yet London offered new challenges—and new allies.

There, Monet reconnected with Pissarro and Daubigny, fellow exiles, and met the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. Their relationship, forged in hardship, would last a lifetime. Durand-Ruel became Monet’s most important patron, championing his work through decades of ups and downs.

London’s mists, parks, and river scenes presented a new set of atmospheric problems for Monet to solve. He embraced them with fascination and frustration—emotions he would revisit when he returned to London more than thirty years later to paint its fog-shrouded bridges and Parliament.

This chapter in Monet’s life is a crucible of emotion and innovation. Personal hardship, romantic devotion, and artistic daring collided to produce the first glimmers of Impressionism. Through it all, Monet remained true to his vision—painting not what he saw, but what he felt.

“My first thought was that I was done for. My boots, stockings and coat were soaked through… the palette had hit me in the face and my beard was covered in blue and yellow… the worst thing was that I lost my painting which soon disintegrated along with the easel.”

It was a moment of chaos, but also of commitment. Monet’s willingness to risk physical harm for the sake of a canvas speaks to the depth of his artistic obsession.

This chapter in Monet’s life is a study in resilience. Amid personal loss, financial instability, and artistic tension, he continued to expand his vision—seeking not just to paint what he saw, but to capture the very sensation of seeing.

Color Unbound: The Mediterranean and Monet’s Emotional Palette

For an artist like Claude Monet—whose sensitivity to color had been honed in the muted, often melancholic landscapes of northern France—the Mediterranean presented a visual shock. The intense blues of sea and sky were, at first, “appalling” and “beyond me,” he admitted. But the challenge of mastering this new light became a turning point. By the 1880s, Monet’s palette had shed its lingering ties to naturalistic color. His canvases—such as Rocks at Belle-Île and Poppy Fields at Giverny—were worked and reworked with thick, vivid pigment, transforming color into a language of emotion.

These paintings were no longer mere impressions of light—they were expressions of feeling, of memory, of the artist’s psychological relationship to the landscape. Monet had begun to paint not just what he saw, but what he felt.

The Meules Series and the Rise of Serial Vision

After the death of Ernest Hoschedé in 1892, Monet scaled back his travels and turned his attention once again to the landscape around his home. Obsessed with capturing the “fugitive effect”—the elusive moment when light and atmosphere converge—he began working on multiple canvases at once, each tuned to a specific condition of light.

The first major result of this method was the Meules (Grain Stacks) series, begun in the mid-1880s and exhibited at Durand-Ruel’s gallery in 1891. These were not haystacks, but stacks of wheat and oats—ordinary rural forms elevated to extraordinary visual phenomena.

The series was a sensation. Pissarro, somewhat exasperated, wrote to his son Lucien:

Collectors, especially in America, paid thousands of francs for each canvas. But beyond the financial success, the series marked a philosophical shift. Monet was no longer painting objects—he was painting time, perception, and presence. As Kandinsky later observed:

This abstraction through repetition became a hallmark of Monet’s late style. The Poplars series (1891), Rouen Cathedral (1894), and Mornings on the Seine (1896–97) continued this exploration, each series a meditation on light, rhythm, and the dissolution of form.

London, Venice, and the Final Travels

In the late 1890s and early 1900s, Monet embarked on his last major journeys. He returned to London, where he painted over 100 views of the Thames by 1904—capturing the city’s fog, bridges, and Parliament in a haze of color and atmosphere. In 1908, he made his final expedition to Venice, producing luminous views of canals and palazzos that shimmer with reflection and reverie.

These works were not travel souvenirs—they were philosophical inquiries into the nature of perception itself.

Giverny: The Garden as Vision

With his paintings now commanding high prices, Monet was finally able to realize a lifelong dream: to create a living canvas. He purchased land adjacent to his house in Giverny, diverted a stream, and built a water garden complete with a Japanese bridge. Over time, the garden expanded into a floral wonderland—a monumental concept of color, form, and seasonal change.

“What I need most of all are flowers, always, always,” he said.

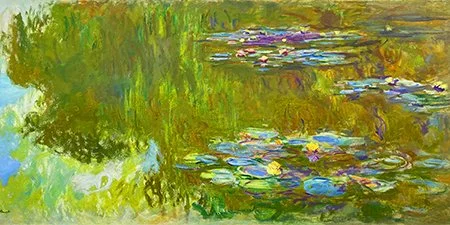

His attention turned to the waterscape of the lily pond. The Nymphéas (Water Lilies) series became his obsession. “These landscapes of water and reflections have become an obsession,” he told Geffroy in 1908. “It’s quite beyond my powers at this age, but I need to succeed in expressing what I feel.”

In 1909, forty-eight of these canvases were exhibited at Durand-Ruel’s gallery. They were not just paintings—they were immersive environments, precursors to installation art, and expressions of pure visual meditation.

The Décorations: A Gift to France

Encouraged by Georges Clemenceau, Monet envisioned a monumental cycle of Water Lilies to be donated to the French state. The plan was ambitious: a series of massive canvases to be housed in a specially designed oval room. The Orangerie near the Louvre was chosen as the site, though political and logistical complications made the project seem, at times, impossible.

In 1911, Alice Monet died. In 1914, his son Jean passed away. Monet, now seventy-four, was cared for by his stepdaughter Blanche Hoschedé-Monet. Despite grief and declining health, he pressed on.

To accommodate the scale of the décorations, Monet proposed building a new studio. As World War I raged around him, he supervised its construction and continued working in his old studio. Cataracts clouded his vision, making color difficult to discern. In frustration, he destroyed several canvases. An operation in 1923 restored partial sight, allowing him—at eighty-three and dying of cancer—to nearly complete the cycle.

The Final Light

Monet died on December 5, 1926, a month after his eighty-sixth birthday, with Clemenceau at his side. He had lived just long enough to see the completion of his final masterpiece—a gift to France, a culmination of decades of devotion to light, nature, and the fleeting moment.

Geffroy wrote of the lily pond:

“There he found, as it were, the last word on things, if things had a first and last word. He discovered and demonstrated that everything is everywhere, and that after running round the world worshipping the light that brightens it, he knew that this light came to be reflected in all its splendour and mystery in the magical hollow surrounded by the foliage of willow and bamboo, by flowering irises and rose bushes through the mirror of water from which burst strange flowers which seem even more silent and hermetic than all the others.”

The Last Canvases

In the final years, Monet returned to the Japanese bridge and the garden at Giverny. These late works are marked by violent, feverish brushstrokes—an inferno of color, a last challenge to sunlight. They are not quiet reflections, but bold declarations. The Impressionist who once sought to capture the fleeting now painted with urgency, as if racing time itself.

Six months before his death, Monet wrote:

". . . in the end the only merit I have is to have painted directly from nature before the most fugitive effects, and it still upsets me that I was responsible for the name given to a group, most of whom had nothing Impressionist about them..."

Monet outlived two wives, a son, the Second Republic, the Second Empire, and all his contemporaries—Pissarro, Degas, Renoir. His work was celebrated across the world, fetching enormous prices. But his true legacy lies not in fortune, but in vision: a lifelong pursuit of light, color, and truth.

The Bench 1873

Camille Monet in Japanese Costume 1875

Boulevard des Capucines 1873

Artists Garden at Vetheuil

The Luncheon 1868

Hunting 1876

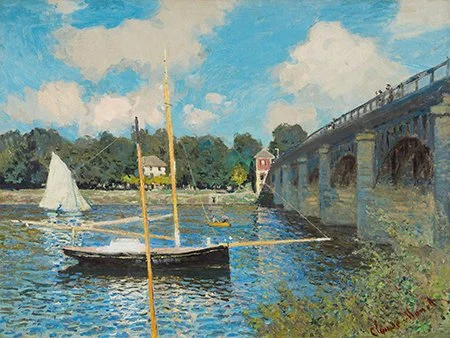

The Bridge at Argenteuil, 1874

Hauling a Boat Ashore, Honfleur 1864

Jar of Peaches 1866

Poppies in a China Vase, 1883

Passage On Waterlilly Pond, 1919

The Garden, Hollyhocks 1876

Flowers and Fruit 1869

The Studio Boat 1876

The Avenue 1878

Woman with a Parasol, 1875

In the Meadow 1876

The Artist's House Seen from the Rose Garden, 1923

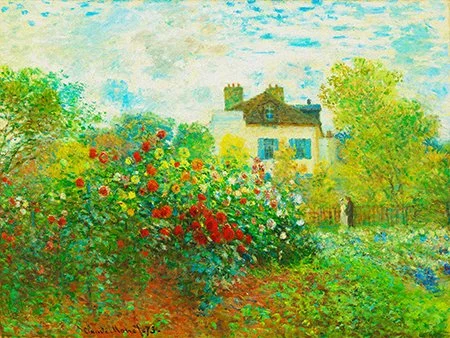

Artist's Garden in Argenteuil, 1873

Water Lilies (Agapanthus), 1920

Boats Lying at Low Tide at Fecamp, 1881

The Water Lily Pond, 1918

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1866

Fishing Boats Leaving the Port of Le Havre 1874