Picture with Three Spots, No. 196, 1914

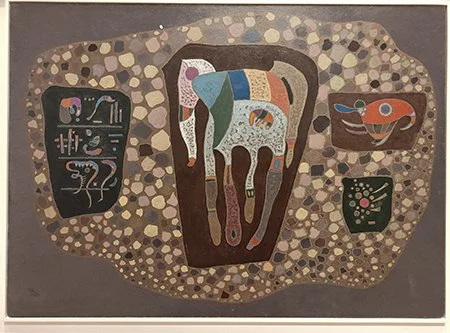

Various Actions, 1941

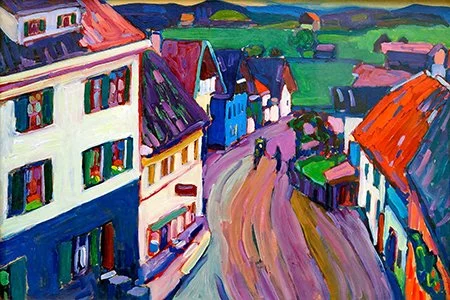

View from the window of Griesbrau, 1908

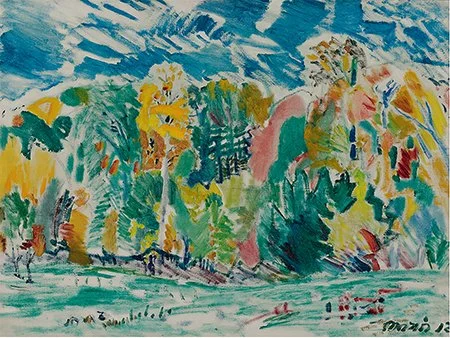

Autumn II, 1912

Squares with Concentric Circles, 1913

Three Pillars, 1943

Blue Circle, 1922

Soft Pressure, 1931

Blue Segment, 1921

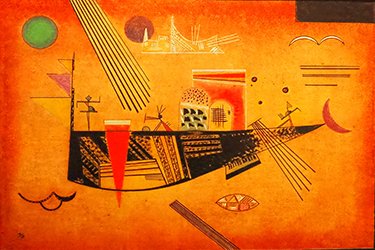

Yellow Painting, 1938

Bright Unity, 1925

Composition 7, 1913

Yellow-Red-Blue, 1925

Snowy Landscape (1866-1944)

Composition X, 1939

Composition_6, 1913

Dominant Curve, 1936

Fragments,_May_1943

Impression III (Concert), 1911

"In Blue “, 1925

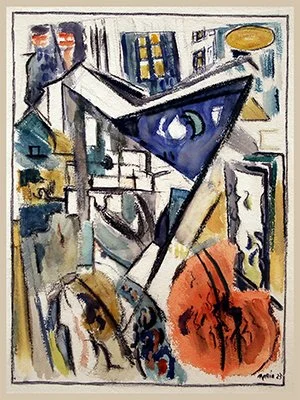

"Inner Alliance" (1929)

Launisch, 1930

RedKnot 1936

Wassily Kandinsky

Expressionism

Vasily Kandinsky: Architect of the Abstract Spirit

Vasily Kandinsky didn’t just paint—he theorized, taught, organized, and inspired. His legacy in modern art is built not only on his pioneering abstract works, but on his belief that painting could be a spiritual force. Through decades of experimentation and reflection, Kandinsky helped redefine what art could be: not a mirror of the visible world, but a language of inner necessity.

A Late Start, A Lifelong Calling

Born in Moscow in 1866 and raised in Odessa, Kandinsky showed early sensitivity to color and form. But he delayed his artistic calling until age 30, leaving behind a promising career in law and economics to study painting in Munich. His decision was bold, driven by a quiet but persistent inner fire.

In Munich, Kandinsky immersed himself in art school, surrounded by younger students. His intellectual depth made him a respected teacher at the Phalanx school, even before his technical skills had fully matured. His early paintings—landscapes, city scenes, and seasonal studies—were modest in scale and traditional in style. But even then, he painted from memory rather than direct observation, hinting at a growing interest in internal vision over external reality.

Travel, Experimentation

Between 1900 and 1908, Kandinsky produced hundreds of works while traveling extensively through Europe and North Africa. His paintings from this period—beaches in Holland, seascapes in Italy, and luminous scenes from Tunisia—show increasing confidence and complexity. He began incorporating figures, including romantic depictions of horsemen and portraits of Gabriele Münter, his student and companion.

These years were formative, filled with experimentation and exploration. Kandinsky absorbed influences from Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Art Nouveau, though he remained cautious about adopting styles that didn’t align with his inner vision. His prints and paintings began to reflect a synthesis of these movements, filtered through his own evolving philosophy.

The Murnau Breakthrough

In 1908, Kandinsky and Münter settled in Murnau, a quiet village in the Bavarian Alps. This marked a turning point. His landscapes became more abstract, his brushwork more fluid, and his colors more expressive. Nature’s details began to dissolve into autonomous shapes and hues.

By 1910, Kandinsky had completed the first of his “Compositions”—a series of ten paintings he considered visual summations of his artistic journey. These works abandoned descriptive function entirely, projecting emotional and spiritual realities through pure form. He had arrived at abstraction not by rejecting nature, but by transcending it.

The Blue Rider and the Rise of Theory

Kandinsky’s influence extended beyond the canvas. In 1909, he became president of the New Artists’ Association in Munich, but tensions between his radical vision and the group’s conservatism led to his resignation in 1911. That same year, he co-founded the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) with Franz Marc—a short-lived but legendary initiative that reshaped modern art.

The Blue Rider was not a movement in the traditional sense. It was a platform for diversity and dialogue, embracing folk art, music, and global traditions. Kandinsky’s own works reflected Bavarian glass painting and other vernacular forms, while the group’s exhibitions revealed a shared sensibility among artists like Münter, Jawlensky, Werefkin, Macke, Marc, and Klee.

The Blue Rider Almanac, published in 1912, became a landmark in art theory. Kandinsky’s essays—especially “On the Question of Form”—argued that abstraction and realism were not opposites but parallel paths, each valid when driven by “inner necessity.” He envisioned a spiritual reawakening through art and proposed a new kind of stage composition that fused music, color, and movement. His theatrical scenario, The Yellow Sound, offered a prototype for modern multimedia performance.

On the Spiritual in Art

Kandinsky’s treatise On the Spiritual in Art, written in 1910 and published in 1911, remains his most important theoretical work. It argued that art must be driven by inner necessity, not external rules. Form, he insisted, is merely a vessel for spiritual intent. Borrowing from music, Kandinsky dismissed the idea of “dissonance” as arbitrary—what matters is the authenticity of the artist’s inner voice.

The second half of the book focused on color, treating it as a living force with psychological impact. Kandinsky believed that colors interact like personalities, and that their relationships with shapes—circles, triangles, squares—could be organized into a kind of visual grammar. This idea paralleled Schoenberg’s Theory of Harmony, written around the same time.

Yet Kandinsky was cautious. He warned against abstraction that lacked substance, just as he criticized realism that ignored the spiritual. His goal was not decoration, but revelation. He believed that painting must speak in its own language, independent of nature, and that true abstraction required the complete dissolution of familiar imagery into autonomous forms.

Moscow and the Russian Avant-Garde.

Kandinsky’s return to Moscow from 1916 to 1921 placed him in the midst of revolutionary change. He joined the People's Commissariat of Enlightenment (Narkompros), working alongside radical figures like Vladimir Tatlin to promote contemporary art through state-funded museums and exhibitions. He also helped found Inkhuk—the Institute of Artistic Culture—where he clashed with younger artists like Aleksandr Rodchenko over the role of emotion versus structure in art.

Though his output during this time was limited, the period was one of deep reflection. Personal upheavals—including his separation from Münter, marriage to Nina Andreevskaia, and the loss of his young son—added emotional weight to an already turbulent time. Yet by the early 1920s, Kandinsky’s work began to show renewed clarity, with defined shapes and recurring motifs like the perfect circle.

The Bauhaus Years: Geometry and Synthesis

Kandinsky joined the Bauhaus in 1922, first in Weimar and later in Dessau. Though the school emphasized applied arts, he was eventually allowed to teach painting on his own terms. His output surged, and his style evolved toward a more geometric, rational abstraction.

In Dessau, Kandinsky’s compositions became increasingly sophisticated. He explored the relationship between planes, textures, and colors, often subdividing canvases vertically to create contrast and harmony. His treatise Point and Line to Plane, published during this period, formalized his theories of structure and spatial dynamics.

Circles became central icons, replacing earlier figurative motifs. Shapes floated in space, intersected, and merged into rhythmic compositions. His titles shifted from descriptive to poetic—Blue Painting, Pink Square, Capricious, Brown Silence. The Bauhaus years marked a consolidation of his abstract language—rigorous yet expressive, systematic yet mysterious.

But the political climate grew hostile. The Bauhaus was attacked by right-wing factions and eventually shut down in 1933. Kandinsky, holding on longer than most, finally left Germany and settled in Paris.

Final Years in Paris: Biomorphic Renewal

In Paris, Kandinsky entered a new phase. Living quietly in Neuilly-sur-Seine, he remained independent from Cubism and Surrealism, though he found inspiration in scientific illustrations and microscopic forms. His geometric base softened, giving way to biomorphic shapes—amoebas, moons, and floating organic forms.

Works like Graceful Ascent and Poker Orange revealed a new sensibility: slower rhythms, aqueous textures, and playful intimacy. Titles like Sweet Trifles and An Intimate Celebration reflected this shift. He began naming works in French, just as he had used German during his Bauhaus years.

This final chapter of Kandinsky’s life was one of quiet innovation. His art became more tactile, more humorous, and more alive—anchored not in celestial abstraction, but in the hidden worlds of nature.

To explore Kandinsky’s work and other pioneers of abstraction, visit masterworksprints.com.

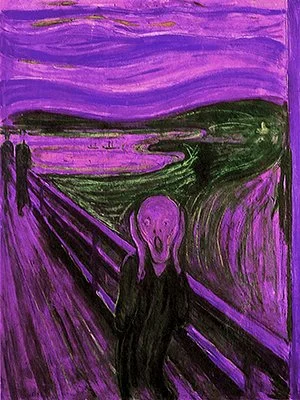

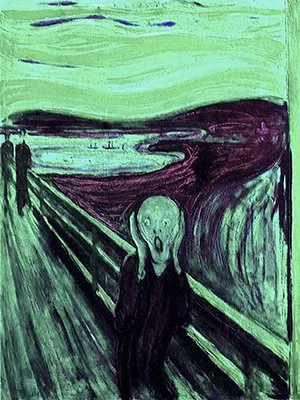

Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch: Painting the Soul’s Landscape

Edvard Munch, like Gauguin and Van Gogh, rejected the conventions of his time—grand landscapes, genteel interiors, and the polished realism favored by the cultural elite. From the beginning, Munch sought something deeper: a visual language that could express the raw, often painful truths of human emotion. “We want more than a mere photograph of nature,” he wrote in 1888. “We want to create… an art that arrests and engages. An art created of one’s innermost heart.”

This conviction led to the creation of his Frieze of Life, a cycle of paintings that trace the arc of human experience—love, desire, jealousy, anxiety, and death. Inspired by personal trauma and philosophical reflection, Munch’s imagery was not conceived as a single series but gradually evolved into one. Each painting was revisited, reworked, and reimagined, revealing more of what Munch called its “soul.”

Symbolism and the Shoreline

Munch’s poetic sensibility and love of contemplative figures on shorelines align him more closely with German Romanticism than with his contemporaries. He admired the moonlit reveries of Caspar David Friedrich and the spiritual landscapes of Philipp Otto Runge. Like Wagner’s Ring cycle, Munch’s Frieze was conceived as a Gesamtkunstwerk—a total artwork that fused emotion, symbolism, and atmosphere.

In a 1918 article, Munch described the Frieze as “a number of decorative pictures… an image of life.” A sinuous shoreline threads through the panels, beyond which lies the restless ocean—symbol of the unconscious, of eternity. Beneath the trees, life unfolds in all its joy and sorrow.

The Soul in Paint

Munch’s belief in the soul as a metaphysical presence within each painting was shaped by his admiration for Nietzsche and Dostoevsky. Nietzsche’s idea that behind every material phenomenon lies an eternal prototype resonated with Munch’s view of art as a spiritual act. Dostoevsky’s explorations of the human psyche—especially in The Idiot—deeply influenced Munch’s own efforts to portray the mystical and the subconscious. He saw each painting as a living entity: “I believe that each painting is an individual trying to achieve something of its own.” By reworking his images, he believed he could reveal more of their inner truth.

A Life Rooted in Loss and Legacy

Munch’s upbringing in Kristiania (now Oslo) was steeped in piety and intellectual tradition. His father, a military physician, died suddenly in 1889, triggering a profound emotional crisis. His extended family included scholars, artists, and churchmen—among them Peter Andreas Munch, a historian whose tomb Munch later memorialized in paint and print.

Introduced to art at age 13, Munch enrolled in the National School of Art and Design in 1880. By 18, he was exhibiting in the newly opened National Gallery. His early exposure to both classical and Romantic traditions laid the foundation for a career that would fuse personal anguish with universal themes.

Edvard Munch: A City of Shadows

Kristiania in the late 19th century was a city of rigid moral codes and quiet despair. Until 1912, it was legally required to be confirmed as Lutheran. There was no opera, no ballet—only beer halls and music venues. The city’s social ritual was the daily promenade down Karl Johan Street, where the bourgeoisie paraded in their finest attire. Munch’s Evening on Karl Johan Street (1892) captures this scene with haunting clarity: pale, anxious figures stare directly at the viewer, a motif he would later intensify in Angst.

Industrialization brought rapid growth—and deep suffering. The population surged from 17,000 in 1801 to over 230,000 by 1900. Tuberculosis ravaged the city’s poor, and Munch was marked by its toll: his mother died when he was five, his beloved sister Sophie when he was thirteen. He believed he had inherited a curse—“Disease and Insanity and Death were the black Angels that stood by my Cradle”—and vowed never to marry or have children.

Sex, Disease, and Moral Hypocrisy

Munch’s neuroses were shaped not only by personal loss but by the city’s fraught relationship with sexuality. Though prostitution was banned nationally in 1842, Kristiania permitted it under strict regulation. Women were subjected to humiliating medical inspections and police oversight. The system was rife with corruption, and failure to comply could mean imprisonment. This hypocrisy—moral purity enforced alongside institutionalized exploitation—was central to the work of Henrik Ibsen, whose play Ghosts exposed the devastation wrought by adultery and hereditary syphilis. Munch later designed the stage set for a Berlin production in 1906, a testament to their shared critique of societal norms.

Art as Social Conscience

Munch’s first teacher, realist painter Christian Krohg, also challenged the status quo. His novel Albertine and its companion painting Albertine in the Waiting-Room of the Police Surgeon depicted the brutal treatment of women forced into prostitution. The painting, rendered with the grandeur of history painting, caused a sensation in 1887 and helped prompt legal reform.

Munch absorbed these influences deeply. His painting Inheritance (1898) and its associated print confront the legacy of syphilis with unflinching honesty: women infected by their partners, left to watch the disease destroy their children. It is a searing indictment of gendered injustice and a society that punished the vulnerable while shielding the powerful.

Edvard Munch: From Bohemia to Soul Painting

In the late 19th century, Edvard Munch moved between two worlds: the repressive moral climate of Kristiania and the more permissive, cosmopolitan atmosphere of Paris. While prostitution in Norway was tightly regulated and stigmatized, Paris offered a more fluid social structure. High-class escorts could reinvent themselves through marriage, and artists openly explored the lives of women on society’s margins. Writers like Zola and Flaubert, and painters like Manet, Degas, and Toulouse-Lautrec, turned these women into icons of modernity—figures of desire, despair, and defiance.

Munch’s early artistic path was shaped by this contrast. Though briefly enrolled in engineering to satisfy his father’s expectations, he soon joined the National School of Art and Design in 1881. Encouraged by his cousin Frits Thaulow, a landscape painter who had faced his own battles with artistic conservatism, Munch received a travel grant in 1885 and began to absorb the radical currents of European art.

The Sick Child and the Birth of Expressionism

Munch’s first teacher, Christian Krohg, was a realist with a social conscience. His painting Albertine in the Waiting-Room of the Police Surgeon exposed the brutal treatment of women under Norway’s prostitution laws. But it was Krohg’s Sick Girl (1881)—a haunting image of a dying child—that left a lasting impression on Munch.

In The Sick Child (1885–86), Munch revisited the death of his sister Sophie with raw emotion. The painting’s rough surface, muted palette, and expressive brushwork marked a break from academic finish. Critics dismissed it as incomplete, but Munch defended its honesty: “We can’t all paint fingernails and twigs.” He later called it his first “soul painting”—a work that sought not to depict reality, but to embody feeling.

Life-Painting and the Bohemian Ideal

Munch’s ideas were shaped not by German Symbolists or Strindberg, as some claimed, but by the radical bohemian circle led by Hans Jaeger. Jaeger’s anarchist philosophy rejected religion, marriage, and bourgeois morality. His banned book From the Kristiania Bohemians argued that celibacy, poverty, and sexual repression were the true evils of society. The group’s manifesto included instructions to sever family ties and even commit suicide—a nihilist creed that resonated with Munch’s own sense of existential doom.

Years later, Munch described this period as “Russian” in spirit—a time of blazing new trails in a “Siberian town” still trapped in moral frost. “It was a testing time for many,” he wrote to Pola Gauguin. “To describe it would require a Dostoevsky, or a mixture of Krohg, Jaeger, and possibly myself.”

Edvard Munch: Love, Loss, and the Making of a Modern Artist

In the late 1880s, Edvard Munch entered his first serious love affair with Milly Thaulow, a married woman from a prominent Norwegian family. Their summer rendezvous in Åsgårdstrand provided the emotional and atmospheric backdrop for works like Summer Night: The Voice. Torn between the piety of his upbringing and the bohemian ideals of free love and artistic liberation, Munch found in this tension the fuel for his creative fire.

Though he never fully embraced Hans Jaeger’s radical manifesto—rejecting suicide and severing family ties—Jaeger’s influence was profound. Munch began to express himself with greater emotional intensity, painting Hulda, an early version of his erotic Madonna, and gifting it to Jaeger for his prison cell.

The Frieze of Life: Art from Inner Turmoil

The themes that would define Munch’s Frieze of Life—attraction, jealousy, anxiety, and isolation—grew directly from the emotional chaos of the Kristiania bohemian circle. Oda Lasson, the only woman in Munch’s painting Kristiania Bohemians, embodied the era’s complex entanglements. Her relationships with Jaeger, Krohg, and later Jappe Nilssen—whose brooding presence anchors Melancholy III—reflected the group’s unraveling ideals. Nilssen’s later support as a critic helped legitimize Munch’s work in Norway.

Munch’s own romantic life remained turbulent. After Milly Thaulow left him, he retreated further into solitude. His most painful relationship was with Tulla Larsen, who pursued him across Europe. Their affair ended in a shooting incident in 1902, leaving Munch with a permanently damaged hand—an injury immortalized in one of the earliest surviving X-rays.

Berlin: Scandal and Stardom

In 1892, Munch was invited to exhibit in Berlin by Adelsteen Normann, a fellow Norwegian painter. But his emotionally charged style—especially works like The Sick Child—clashed with the conservative tastes of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s court. The show was shut down after just one week. The Frankfurter Zeitung mocked the reaction: “Art is endangered! An Impressionist, and a mad one at that, has broken into the herd of our fine solidly bourgeois artists.”

To Munch’s surprise, the scandal made him famous. His exhibition reopened in December, and his work began touring across Germany. In Berlin, he joined a vibrant circle of international bohemians who gathered at the Black Piglet tavern—among them August Strindberg, Stanisław Przybyszewski, Holger Drachmann, Jens Thiis, and Richard Dehmel. Their conversations ranged from science and sex to alchemy and Symbolist art.

Drachmann’s fascination with cabaret and the Parisian can-can inspired Munch’s print Tingletangle (1895), a nod to Berlin’s own version of the dance craze. Munch had arrived—not just as a painter of emotion, but as a cultural force.

Edvard Munch: The Frieze of Life

The emotional chaos of the Kristiania Bohemians—marked by tangled relationships, idealism, and heartbreak—provided the raw material for Edvard Munch’s most enduring artistic achievement: the Frieze of Life. Among the muses who shaped its imagery was Dagny Juel, a free-spirited writer and pianist whose beauty and independence captivated many in Munch’s circle. She married the Polish writer Stanisław Przybyszewski, bore him two children, and was later murdered by a jealous lover in Tbilisi in 1901. Munch remained loyal to her memory, writing a heartfelt obituary while the press vilified her for her sexual freedom.

Dagny, along with Milly Thaulow and Tulla Larsen, inspired Munch’s symbolist depictions of women—figures fused from memory, emotion, and myth. In Jealousy II, Przybyszewski’s pale, tormented face appears beside a half-dressed Dagny, with Munch himself in the background. These images were not portraits, but emotional archetypes.

A Poem in Paint

In 1893, Munch began to think in terms of a visual cycle. His exhibition Study for a Series: Love at Unter den Linden in Berlin included six compositions set against the pinewoods and shoreline of Åsgårdstrand, where memories of Milly Thaulow lingered. The works—The Voice, Kiss, Vampire, Melancholy, Moonlight, The Scream, and Death in the Sick Room—traced the arc of love, loss, and existential dread.

By 1896, ten paintings from the series were shown at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris to considerable acclaim. Munch continued to expand the cycle, producing prints under the title The Mirror and exhibiting them in Kristiania in 1897.

From the Modern Life of a Soul

In 1902, Mx Liebermann invited Munch to present the full cycle at the Berlin Secession. Now titled From the Modern Life of a Soul, the works were arranged in four thematic sections:

• I. Seeds of Love – The Voice, Attraction, The Kiss, Madonna

• II. Flowering and Passing of Love – Vampire, Melancholy, Jealousy

• III. Life Anxiety – Evening on Karl Johan Street, The Scream

• IV. Death – Death in the Sick Room, Dead Mother and Child

To complete the circle, Munch added Metabolism, a haunting image of a naked couple beneath a tree rooted in human bones—symbolizing life emerging from death. “It may appear that the motif… stands somewhat apart,” he wrote, “yet it is as necessary for the entire Frieze as a buckle is for a belt.”

A Vision Without a Home

Munch hoped to sell the Frieze as a complete installation, ideally housed in a single room designed to showcase its emotional and architectural unity. “Each individual panel,” he wrote, “should be shown to its total advantage without the overall impression being compromised.” But no buyer came forward.

The cycle was exhibited in Leipzig (1903), Kristiania (1904), Prague (1905), and again in Kristiania in 1918, with new panels replacing those sold to collectors. Though it was never housed as a whole, the Frieze of Life remained central to Munch’s identity. In a photograph taken on his seventy-fifth birthday, he stands in his studio at Ekely, surrounded by fragments of the cycle—a visual testament to a lifetime spent painting the soul.

Scream 01, 1910

Scream 02, 1910

Scream 03, 1910

Scream 04, 1910

Expressionism

John Marin

John Marin: Drawing the Motion of the Modern World

In 1948, a Look magazine survey of museum directors, curators, and critics named John Marin the greatest painter in the United States. It was a remarkable recognition for an artist whose early life gave little hint of such acclaim. Until nearly forty, Marin drifted between careers—working in a wholesale notions house, training as an architect in New Jersey, and studying intermittently at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Art Students League in New York. But through all the uncertainty, one constant remained: drawing. “I just drew,” Marin said. “I drew every chance I got.”

That compulsion to draw was the heartbeat of Marin’s art. It carried him through a formative period in Paris from 1905 to 1909, where he made etchings of European architecture for the tourist trade. But it was in 1908, at the Salon d’Automne, that modernist photographer Edward Steichen saw Marin’s watercolors and was struck by their vitality. Steichen arranged for Marin’s first exhibition at 291 Gallery, the epicenter of modern art in New York. A few months later, Alfred Stieglitz—the gallery’s visionary founder—took Marin under his wing.

The Stieglitz Years: Watercolor as Modernism

When Marin returned to the U.S. in 1909, and permanently in 1910, he quickly established himself as a cutting-edge modernist. His work appeared annually at Stieglitz’s succession of galleries—291, The Intimate Gallery, and An American Place—for most of his career. Stieglitz championed Marin’s use of watercolor, a medium often dismissed as less serious than oil. But Marin’s gestural watercolors of New York’s architecture and Maine’s rugged coastlines became some of the most admired works in Stieglitz’s orbit.

Marin settled in Cliffside, New Jersey, where he kept his studio for most of the year. Beginning in 1914, he and his wife Marie, along with their son John Jr., spent summers in Maine. Critics praised his watercolors in newspapers and magazines, and collectors sought them with growing fervor. Though Marin also painted in oil, it was watercolor that defined him.

“Fewer strokes, still fewer strokes. Fewer strokes must count. A full mellow ring to each stroke,” he wrote to Stieglitz in 1916—a mantra of economy and resonance.

Drawing as Gesture, Drawing as Thought

Marin’s devotion to drawing was not just technical—it was philosophical. From childhood, he drew constantly, both for pleasure and for purpose. He used drawing to record what he saw, test visual ideas, and work out compositions for paintings and prints. In rural places like Maine, he often skipped preliminary sketches, painting watercolors directly on site. But in New York, where the bustle made easel work impossible, he sketched on the move.

“The drawings,” Marin said, “were mostly made in a series of wanderings around about my City—New York—with pencil and paper in—short hand-writings as it were—Swiftly put down.” He used cheap 8 x 10-inch writing pads, bought in bulk, and filled piles of sketchbooks that he consulted in his studio. These drawings weren’t architectural renderings—they were energetic notations of motion and force, capturing the pulse of buildings, crowds, and city rhythms.

“Drawing is the path of all movements Great and Small,” he wrote. “Drawing is the path made visible.”

The Heroic Years and Artistic Maturity

By the 1930s, Marin’s reputation had soared. In 1936, the Museum of Modern Art honored him with a one-man retrospective. That same year, Alfred Stieglitz died, but Marin continued to work with Stieglitz’s widow at An American Place. He remained in New Jersey, summered in Maine, and kept painting with undiminished passion.

His late works—especially Composition VIII, IX, and X—were monumental statements. They balanced firm structure with playful, almost Baroque flourishes, reflecting the relaxed wisdom of an artist in his final chapter. In canvases like Capricious Forms, Marin let his shapes dance with abandon, while works like Two, Etc. reminded viewers of the disciplined elegance of his Bauhaus-influenced years.

Even in his most whimsical moments, Marin’s work remained balanced, structured, and deeply intentional. Titles like Rigid and Bent, Reduced Contrasts, Serenity, and Moderation reflected the paradoxes he explored—freedom within form, emotion within geometry.

Legacy on the Shore

John Marin died in 1953 on the rocky shore of Cape Split, Maine. His work is held in major collections across the country, including the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts and the Colby College Museum of Art, which houses the largest archive of his paintings, drawings, and photographs.

Marin’s legacy is not just in his technique, but in his philosophy. He taught us that watercolor could be bold, that abstraction could be emotional, and that drawing was not just a tool—but a way of seeing, a way of moving through the world.

To explore Marin’s work and other pioneers of abstraction, visit masterworksprints.com.

Castorland, New York,1913

The Battle of Olómpali

The Sea Maine, 1964

Bryant Square, 1932

Astrazione, 1917

The Blue Sea, 1964

Uragano, 1944

Lower Manhattam, 1923

Fifth Avenue, 1933

Lower Manhattan, 1920

Expressionism