Surrealism

Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp: Art as Thought, Irony, and Provocation

Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) remains one of the most radical and influential figures in twentieth-century art. Often described as a “one-man movement” by Willem de Kooning, Duchamp’s work bridged visual art, literature, and philosophy, embodying the cerebral spirit of contemporaries like Marcel Proust and James Joyce. Jasper Johns once called his practice “the field where language, thought and vision act on one another”—a fitting description for an artist who sought to liberate art from mere visual pleasure and return it to the realm of intellectual inquiry.

By the time of World War I, Duchamp had grown disenchanted with what he called “retinal” art—works designed only to please the eye. His mission was clear: “to put art back in the service of the mind.”

From Normandy to New York: A Journey of Reinvention

Born in Normandy, Duchamp spent much of his life moving between Europe and the United States. His early paintings followed the Impressionist and Cézanne-inspired trends of the time, but by 1910, his work began to shift toward Cubism. His landmark painting Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) (1912) exemplifies this transition. While adopting Cubism’s muted palette, Duchamp infused the figure with dynamic motion—breaking from the static, analytical style of Picasso and Braque.

The painting was controversial from the start. Rejected by the Salon des Indépendants for its mechanistic depiction of the female nude and provocative title, it later caused a stir at the 1913 Armory Show in New York. This moment cemented Duchamp’s reputation as a provocateur and opened the door to his eventual relocation to the U.S.

The Readymade and the Rise of Conceptual Art

Duchamp’s most revolutionary contribution came through his invention of the readymade—ordinary, mass-produced objects designated as art simply by the artist’s choice. His first, Bicycle Wheel (1913), combined a wheel and stool into a sculpture that defied traditional notions of craftsmanship and aesthetic value. Duchamp viewed paint itself as an industrial product, calling painting an “assisted-readymade.” In this light, the readymade was not a radical break, but a logical extension of modern materials and thought.

He also embraced chance as a creative force, as seen in 3 Standard Stoppages (1913–14), which introduced randomness into the artistic process. Duchamp’s goal was to shift emphasis from technical skill to conceptual depth—inviting viewers to engage with irony, wordplay, and philosophical paradox rather than visual beauty.

Later readymades included a snow shovel, a bottlerack, and most famously, Fountain (1917)—a porcelain urinal submitted under a pseudonym to a New York exhibition. These works challenged the boundaries of taste, authorship, and artistic legitimacy, transforming industrial detritus into cultural critique.

Dada, Satire, and the New York Circle

Duchamp’s iconoclasm resonated with the Dada movement, which emerged in response to the horrors of World War I and the failures of European conservatism. While European Dada was overtly political, Duchamp’s version—developed in New York alongside Francis Picabia, Man Ray, and collectors like Katherine Dreier and the Arensbergs—was more satirical and cerebral.

His works from this period, especially Fountain, tested the limits of public perception and institutional authority. Through puns, alliteration, and layered humor, Duchamp critiqued not only the art world but also the broader political and economic systems of his time.

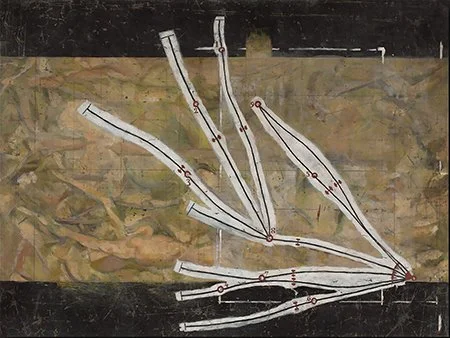

The Large Glass and the Breakdown of Form

Between 1915 and 1923, Duchamp worked on The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even—better known as The Large Glass. This enigmatic piece, housed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, encapsulates Duchamp’s belief that traditional painting and sculpture were inadequate for expressing modern life. Composed of glass, dust, and mechanical imagery, the work reflects his shift toward abstraction and mathematical symbolism.

His preparatory notes and diagrams—later compiled in The Green Box (1934)—reveal a meticulous conceptual framework that blurred the line between art and literature, object and idea. The Large Glass stands as a manifesto against realism and a celebration of intellectual play.

Chess, Legacy, and the Artist as Trickster

In the 1920s, Duchamp famously declared his retirement from art to pursue chess full-time. Yet this retreat was more theatrical than absolute. He continued to influence the art world through quiet interventions and collaborations, maintaining his role as the archetypal artist-provocateur.

Duchamp’s legacy spans Cubism, Dada, Surrealism, and beyond. His ideas laid the groundwork for Pop Art (Andy Warhol), Minimalism (Robert Morris), and Conceptualism (Sol LeWitt). More than any single style or object, Duchamp’s enduring contribution is his permission—indeed, his insistence—that artists challenge norms, question meaning, and redefine what art can be.

He didn’t just change the rules. He made it clear that the rules were always up for debate.

Florine Stettheimer, La Fete, 1917

Portrait of a Man, 1913

Chocolate Grinder (No. 2), 1914

Chocolate Grinder (No. 1), 1913

Salvador Dalí

The Making of Dalí: Genius, Rebellion, and Surrealist Fire

Salvador Felipe y Jacinto Dalí was born on May 11, 1904, in Figueras, Catalonia. His father, a stern and cultured notary, kept a library that sparked Dalí’s early fascination with literature and philosophy. His mother, Felipa Domenech, was the emotional anchor of his childhood until her death in 1921, a loss that deeply marked him.

Dalí’s summers in Cadaqués were filled with vivid fantasies, strange visions, and a heightened sensitivity to the world around him—smells, dreams, animals, and objects all seemed charged with meaning. His artistic talent was recognized early by family friends and mentors, including the German painter Siegfried Burmann, who gifted him his first palette in 1914. By 1917, Dalí was studying drawing under Juan Nuñez and exhibiting Impressionist-inspired landscapes and figures at the Figueras Municipal Theater. He also co-founded the review Studium, writing about the great masters—Goya, El Greco, Dürer, Leonardo, Michelangelo, Velázquez—who became guiding stars in his artistic constellation.

In 1921, Dalí entered the San Fernando Academy in Madrid and lived at the University Residence, a hub of cultural exchange. There, he befriended Federico García Lorca and Luis Buñuel, absorbing Cubism, Futurism, and Purism, and studying the works of Picasso, Gris, Matisse, and De Chirico. Though initially shy and eccentric, Dalí soon became a flamboyant figure in the avant-garde scene. His first solo show came in 1925 at the Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona, featuring works like Portrait of My Father and Girl Standing at the Window.

Dalí’s refusal to conform led to his expulsion from the Academy in 1926. He traveled to Paris, met Picasso, and returned to Madrid with a sharpened sense of rebellion. His second solo show followed in early 1927, and he began contributing essays and articles to avant-garde journals. His style shifted toward Surrealism, culminating in the co-creation of the film Un chien andalou with Buñuel in 1929—a shocking, dreamlike work that cemented his place in the Surrealist movement.

That same year, Dalí met Gala, the wife of poet Paul Eluard. Their love affair was immediate and lifelong. He exhibited in Zurich and Paris, where his painting Dismal Sport stirred both curiosity and controversy. In 1930, Dalí and Buñuel released L’âge d’or, a film so provocative that it was violently shut down by right-wing protesters. Dalí continued to publish manifestos and essays, developing his theory of “paranoiac-critical” method and the double image.

His relationship with Gala caused a rupture with his father, but also marked a turning point. With proceeds from the sale of The Old Age of William Tell, Dalí bought a cottage in Port Lligat, where he and Gala would spend their summers—a sanctuary for the surreal. These formative years reveal the intensity and complexity of Dalí’s evolution: from precocious dreamer to radical visionary. His early works, writings, and collaborations laid the foundation for a career that would redefine modern art.

Dalí’s Surreal Odyssey: From Persistence to Perpignan

In June 1931, Salvador Dalí exhibited 24 works at the Pierre Colle Gallery in Paris, including The Persistence of Memory—the now-iconic painting that would appear again in the Surrealist retrospective at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York the following year. That same year, he published Love and Memory, a poem that echoed his fascination with time and emotion.

By 1932, Dalí and Gala were spending summers in Port Lligat, joined by friends like René Crevel. He continued to write and publish, including the film scenario Babaouo, though the film was never made. To support his work, the Zodiac group formed—an elite circle of patrons who pledged to buy one painting per month. Dalí’s essays for Minotaure and illustrations for Les Chants de Maldoror showcased his growing influence in both literary and visual circles.

His controversial film L’âge d’or (1930) had already stirred outrage, and his manifesto The Putrefied Donkey began to articulate his paranoiac-critical method. His relationship with Gala deepened, even as it fractured ties with his father. With proceeds from The Old Age of William Tell, Dalí purchased a cottage in Port Lligat, which became his lifelong retreat.

In 1934, Dalí arrived in New York and declared himself the only true Surrealist. He moved effortlessly between press conferences and high-society galas, building his reputation with flair. His essay The Conquest of the Irrational (1935) formalized his artistic philosophy. By 1936, he was living near Sacré-Coeur in Paris and nearly suffocated while giving a lecture in a diving suit—a stunt that became legend.

The Spanish Civil War forced Dalí and Gala to flee Port Lligat. In December 1936, he appeared on the cover of Time magazine, cementing his fame in the U.S. His 1937 visit to Hollywood led to a surreal collaboration with Harpo Marx and the unproduced script Giraffes on Horseback Salad. That year, he exhibited Metamorphosis of Narcissus in Paris and met Freud in London, a pivotal moment in his intellectual development.

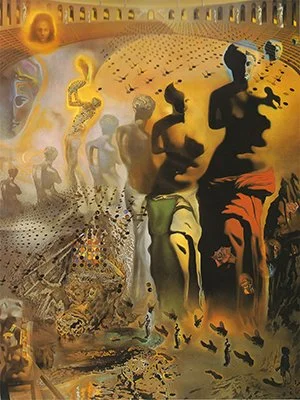

Despite tensions with the Surrealist group, Dalí continued to participate in exhibitions. His Rainy Taxi installation in 1938 was a sensation. He caused further scandal with his window display at Bonwit-Teller and his Dream of Venus installation for the World’s Fair. His ballet Bacchanale premiered at the Metropolitan Opera in 1939, with Dalí designing sets and costumes.

As World War II loomed, Dalí returned to the U.S. in 1940, settling first in Virginia. He designed another ballet, Labyrinth, and held a major retrospective at MoMA in 1941. His creative output exploded: jewelry, advertisements, novels, and ballets. His autobiography The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí was published in 1942. He met Eleanor and A. Reynolds Morse, who became major collectors of his work.

In 1945, Dalí collaborated with Hitchcock on Spellbound and with Disney on Destino, which remained unfinished. He held exhibitions across the U.S. and illustrated works by Cellini, Montaigne, and Shakespeare. Returning to Europe in 1949, he presented Madonna of Port Lligat to Pope Pius XII and worked with Visconti on As You Like It.

His Mystical Manifesto (1951) marked a turn toward Catholic themes. He gave famously theatrical lectures, including one in 1958 where he was followed by a 12-meter loaf of bread. His ballet Le ballet de Gala premiered in Venice in 1961. In 1962, he unveiled Battle of Tetuan in Barcelona and published The Tragic Myth of Millet’s Angelus and Diary of a Genius.

Dalí’s Perpignan Station was exhibited in 1965, followed by a massive show of 370 works in New York. In 1974, he inaugurated his Theater Museum in Figueras. He was elected to the Académie Française in 1979 and honored with a retrospective at the Pompidou Center. Gala’s death in 1982 devastated him. King Juan Carlos named him Marquis of Púbol that July.

In his final years, Dalí lived with the solemnity of a monarch. He attempted suicide, suffered burns in a fire, and withdrew into seclusion. He died on January 22, 1989, leaving behind a legacy as singular as his imagination.

At Masterwork Prints, we honor artists like Dalí who defied convention, embraced contradiction, and transformed the visual language of the twentieth century. His journey reminds us that genius often walks hand-in-hand with madness—and that both can be profoundly beautiful.

Surrealism